Will I survive a bear attack? I’d been asking the wrong question. Being alive is one big risk and it will end in death, but the bridge between those two things is love.

Will I survive a bear attack? I’d been asking the wrong question. Being alive is one big risk and it will end in death, but the bridge between those two things is love.

After this investigation, my recommendation is to spend your time falling in love with the people and the world around you. Don’t let a fear of death eclipse your life. Run towards love, fight for it, and die for it.

When I was a child, my family went camping most summers, often at Saltery Bay, a significant drive (and two ferry rides) up B. C.’s optimistically named ‘Sunshine Coast.’ I wasn’t – and still am not – particularly outdoorsy, and I am irrationally afraid of starfish, and, less irrationally, of barnacles, so I am not sure I ever swam in the water off the rocks where we hung out day after day. I loved the tidal pools, though, full of mussels and crabs and tiny fish, and I loved staking out our favorite picnic table, the only one with any shade, early in the morning with my dad (the other families must have hated us!). We played Scrabble there, and painted rocks, and colored in our coloring books. Back at the campsite after dark, we played card games and colored some more and designed outfits for my beloved paper doll Hitty (named for and patterned after the wooden doll in this book) and sang songs by the fire when my dad played his guitar.

Every so often on these trips my dad would make a joke to my mother about bears. I am morally certain, now, that she never found them funny. I don’t remember ever taking bears seriously myself. I also don’t remember any particular precautions that we took to keep them at bay. But the elegant and informative B. C. Parks website (no such thing existed during my childhood in the 1970s and 1980s, of course) does say that “bears, cougars, wolves, and other potentially dangerous animals may be present,” and gives advice about how to keep yourself safe.

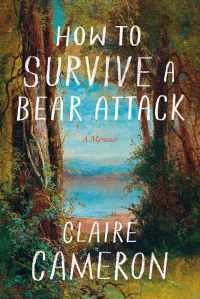

We were more wary about bears when we camped at Manning Park, I guess because it’s in the mountains and bears were known to roam there. In fact, I think I remember us all getting into the car once because we spotted a bear in our vicinity, though I am not 100% sure about this.* If we did, it can’t have helped my mother’s anxiety about these burly threats to her family. As Claire Cameron is at pains to emphasize in her new memoir How to Survive a Bear Attack, bear attacks are vanishingly rare. The couple whose grim deaths on a camping trip in 1991 are the anecdotal center of her story were, statistically speaking, in much greater danger on the drive to Algonquin Park; as she also points out, the woman of the pair was – again, statistically speaking – more likely to be killed by her male companion than by a bear. Still, if you are the rare target of a charging bear, those statistics are not going to feel reassuring, and if a bear does actually attack you, you are in extreme danger.

We were more wary about bears when we camped at Manning Park, I guess because it’s in the mountains and bears were known to roam there. In fact, I think I remember us all getting into the car once because we spotted a bear in our vicinity, though I am not 100% sure about this.* If we did, it can’t have helped my mother’s anxiety about these burly threats to her family. As Claire Cameron is at pains to emphasize in her new memoir How to Survive a Bear Attack, bear attacks are vanishingly rare. The couple whose grim deaths on a camping trip in 1991 are the anecdotal center of her story were, statistically speaking, in much greater danger on the drive to Algonquin Park; as she also points out, the woman of the pair was – again, statistically speaking – more likely to be killed by her male companion than by a bear. Still, if you are the rare target of a charging bear, those statistics are not going to feel reassuring, and if a bear does actually attack you, you are in extreme danger.

Claire Cameron was not attacked by a bear. The title of her book is not exactly misdirection: in fact, How to Survive a Bear Attack is full of information about bear attacks and how to survive them. The sections have titles like “When to Play Dead,” “When to Fight,” and “A Time to Surrender.” Cameron had turned to the wilderness after her father’s death from cancer, and had found courage and strength in the beauty of the Canadian landscape and her own active engagement with it, hiking, climbing, paddling, and camping. Anyone with these interests has to think about bears, and Cameron often had. A turning point in what became a “full-blown bear obsession” was a close encounter with one when she was planting trees in Northern Ontario. She knew the story about the couple who had died in Algonquin Park, but the cinnamon bear she saw on that expedition was an “apple-eating bear” smart enough to pry the lid off the Tupperware container he’d taken out of her backpack (which the bear had lifted from a van when someone foolishly left the window down a bit) and eat the peanut butter sandwiches inside.

Over the years, Cameron had been plenty close to bears – and also “stood close enough to mountain lions, and jumped over rattlesnakes.” It was only practical to know something about what to do in the event that a bear saw her as a threat, or as prey. But it had never come to that, and then at 45, she got a diagnosis that changed everything. “It was only now,” she says, “that I realized how foolish I was. I’d been preparing to fight a bear when the thing that would most likely kill me – my own DNA – had been lurking in a place much closer.” What she is fighting is cancer, specifically the rare and threatening form of melanoma that led to her father’s death at only 42. At the time of her own diagnosis, Cameron was 45.

Some of the strongest writing in the book comes in the passages where Cameron reflects on how it feels and also what it means to understand that “nature” is not a setting for our lives but that our lives are themselves natural. In the wake of this frightening news, she and her husband hold each other, wonder what to tell their kids, and contemplate a future without the “false sense of security” that comes from the walls we build around ourselves. “Every now and then,” she says,

something happens. A reminder. The mask of control slips to the side and there is a glimpse of what lies behind. We are subject to natural forces. We are delicate, vulnerable creatures, no matter how much time we spend telling ourselves otherwise. Our teeth are blunt, our skin is thin, and our hearts flutter close to the surface. We are subject to the pull of the moon; we can be shifted by the tides and pushed by the wind.

Later, in the context of the deadly bear attack in Algonquin Park, she will note specifically the vulnerability of the backs of our necks: “a person approached from behind with force stands little chance.” This, she thinks, is how Carola died – instantly, at least, unlike her partner Ray, who seems to have fought with everything he had. (Fair warning: parts of this book are quite graphic about the damage bears can do.)

What does a bear attack have to do with cancer? Is it just a metaphor? Yes, partly: the book is about Cameron’s illness and her desire to survive it, and so the section headings (especially 12, “How to Live”) take on dual meaning. But Cameron is also, still, obsessed with literal bears, and just as her turn to the outdoors helped her come back to life after her father’s death, so her strong and initially inexplicable fixation on finding out what exactly happened at that campsite in 1991 helps her find purpose, motivation, and eventually meaning after the surgery that, provisionally anyway, removes her cancer but leaves her weakened and unmotivated. The quest starts with an anomaly, perhaps a mistake, in a note she’d written about the case for her earlier novel The Bear. Suddenly “every hour became urgent”:

By that time, I had lived three years longer than my dad. This felt like borrowed time. I made a list of questions. I was sore and tired. I suspected I might be dying, but finding answers became more pressing than fear.

The next big shift comes as she pursues those answers and comes across a photograph of the killer bear. She had always focused on the people, the victims, the search party, the mourners, herself. Only at that moment does she realize there’s another point of view: the bear’s. Bears “are individuals. They do individual things.” To complete her story of that fatal meeting, she “needed to understand this bear on his terms, not mine.”

The bear’s story becomes the third strand in the narrative Cameron weaves, which combines her personal story, the story she puts together (including various testimonies and evidence) about Carola and Ray’s horrific final day, and sections from the point of view of the bear that attempt to portray him as a character in his own right – personality, curiosity, hunger, all as far as possible conveyed as aspects of what we might call bearishness. I admit I found these parts not completely convincing, not so much because they are inevitably speculative but because, well, it’s a bear. Cameron knows, and tells us, a lot about bears, including how smart they are, but this bear thinks, remembers, and plans to a degree that seems improbable. I think the idea probably was to make explicit what in reality is more implicit or instinctual; the risk is anthropomorphizing him, and while I think Cameron makes a valiant effort not to do that, still, well, it’s a bear. I still found it very interesting to learn so much about a bear’s life, though! And I liked the connections Cameron makes to Beowulf, one of the stories her father had loved to share with her. Toni Morrison, in an essay on Beowulf, “makes the point that nowhere in the story do people ask questions about why Grendel was hell-bent on eating them.” “When I followed Morrison’s thought,” Cameron explains, “I understood that the bear wasn’t beyond comprehension . . . It felt like trying to reach out and touch Grendel.”

The bear’s story becomes the third strand in the narrative Cameron weaves, which combines her personal story, the story she puts together (including various testimonies and evidence) about Carola and Ray’s horrific final day, and sections from the point of view of the bear that attempt to portray him as a character in his own right – personality, curiosity, hunger, all as far as possible conveyed as aspects of what we might call bearishness. I admit I found these parts not completely convincing, not so much because they are inevitably speculative but because, well, it’s a bear. Cameron knows, and tells us, a lot about bears, including how smart they are, but this bear thinks, remembers, and plans to a degree that seems improbable. I think the idea probably was to make explicit what in reality is more implicit or instinctual; the risk is anthropomorphizing him, and while I think Cameron makes a valiant effort not to do that, still, well, it’s a bear. I still found it very interesting to learn so much about a bear’s life, though! And I liked the connections Cameron makes to Beowulf, one of the stories her father had loved to share with her. Toni Morrison, in an essay on Beowulf, “makes the point that nowhere in the story do people ask questions about why Grendel was hell-bent on eating them.” “When I followed Morrison’s thought,” Cameron explains, “I understood that the bear wasn’t beyond comprehension . . . It felt like trying to reach out and touch Grendel.”

The bear is a bear; the bear is Grendel, embodiment of our oldest and deepest fears; the bear is cancer; the bear is nature. They are all, in their own way, wild – and the wilderness is not somewhere else, separate, held back or “conserved” within inside the arbitrary boundaries of a park:

The wilderness has never been empty. It doesn’t have borders. It’s a word that defines a relationship between the people, the wildlife, and the land. It’s ancient and will be here long after I’m gone. I can’t control where or how it goes. It’s under the carpet, in the alley behind my house, in the lake, inside a glacier, and on an island in Algonquin Park. It’s inside the mind of a black bear.

It’s also much closer. It lives in my cells. To some, those cells might have a mutation. To me, they are cells inherited from my dad. I have cancer. It’s wild inside me.

Cameron completes her investigation and writes her account of what happened, to Carola and Ray, to the bear, to her father, and to herself. There is ultimately no comforting answer to the question that once preoccupied her: “If I’m attacked by a bear, will I survive?” None of us survive, so the question, the preoccupation, is itself misguided, she concludes. “Being alive is one big risk and it will end in death”; instead of running away from bears (which, just by the way, is not a good move in the case of a literal bear attack) we should “run towards love, fight for it, and die for it.” The lesson might seem a little pat, even trite, but the urgency and the poignancy of it are real for Cameron, which gives it power, and besides, things are often trite precisely because they are true. There’s a reason a story as old as Beowulf can still speak to us, can still give Cameron the words she needs to face the end: “I’ll let go then, of all my holdings, my throne, my carefully guarded bones.”

*I checked with my parents and my mother confirms: “The night before, a bear prowled around our tent. At lunch the next day when many were enjoying themselves by a stream at a picnic site, a bear wandered in and I was the only one who made my family get in the car.” That seems a very sensible precaution to me!

There is no good way to say this—when the police arrive, they inevitably preface the bad news with that sentence, as though their presence had not been ominous enough . . .

One of these was Kaliane Bradley’s The Ministry of Time, which I got interested in because Bradley was a brilliant guest on Backlisted. She was talking about Monkey King: Journey to the West—this was

One of these was Kaliane Bradley’s The Ministry of Time, which I got interested in because Bradley was a brilliant guest on Backlisted. She was talking about Monkey King: Journey to the West—this was

Anders Lustgarten’s Three Burials is also quite violent and action-driven, but underlying it is a less cynical or discouraging vision than I felt was at the core of A Line in the Sand. Its Thelma and Louise-style plot (a connection made explicit in the novel itself) focuses on Cherry, a nurse who happens upon the body of a murdered refugee (we already know him as Omar) on a British beach. Cherry is carrying a lot of grief and trauma, including her wrenching memories of the worst of the COVID pandemic (people currently downplaying the severity of the crisis and restricting access to the vaccines that have helped us get to a better place would benefit from the terse but powerful treatment it gets here). She is also grieving her son’s death by suicide, and the resemblance of the dead man to her son adds to her determination to somehow get his body to the young woman whose photo he was clutching when he died.

Anders Lustgarten’s Three Burials is also quite violent and action-driven, but underlying it is a less cynical or discouraging vision than I felt was at the core of A Line in the Sand. Its Thelma and Louise-style plot (a connection made explicit in the novel itself) focuses on Cherry, a nurse who happens upon the body of a murdered refugee (we already know him as Omar) on a British beach. Cherry is carrying a lot of grief and trauma, including her wrenching memories of the worst of the COVID pandemic (people currently downplaying the severity of the crisis and restricting access to the vaccines that have helped us get to a better place would benefit from the terse but powerful treatment it gets here). She is also grieving her son’s death by suicide, and the resemblance of the dead man to her son adds to her determination to somehow get his body to the young woman whose photo he was clutching when he died. A huge wave of fatigue rinsed me from head to foot. I was afraid I would slide off the bench and measure my length among the cut roses. At the same time a chain of metallic thoughts went clanking through my mind, like the first dropping of an anchor. Death will not be denied. To try is grandiose. It drives madness into the soul. It leaches out virtue. It injects poison into friendship, and makes a mockery of love.

A huge wave of fatigue rinsed me from head to foot. I was afraid I would slide off the bench and measure my length among the cut roses. At the same time a chain of metallic thoughts went clanking through my mind, like the first dropping of an anchor. Death will not be denied. To try is grandiose. It drives madness into the soul. It leaches out virtue. It injects poison into friendship, and makes a mockery of love.

You decide to water the little tree. You plan what is to be done. Take your walking cane for extrabalance security when you reach the ground cover and the rocks between the gravel and the faucet for the house. Then out the door, down the stone steps, turn right on the gravel, walk with cane thirty to forty feet to the spot at the corner of the house . . .

You decide to water the little tree. You plan what is to be done. Take your walking cane for extrabalance security when you reach the ground cover and the rocks between the gravel and the faucet for the house. Then out the door, down the stone steps, turn right on the gravel, walk with cane thirty to forty feet to the spot at the corner of the house . . .  Sunday 9 September

Sunday 9 September At first I was thinking that not much was really happening in this section, but then it struck me that of course there is a war on, as we are reminded by several passing references to German prisoners working on the nearby farms: “To picnic near Firle,” she reports on August 11, for example, “with Bells &c. Passed German prisoners, cutting wheat with hooks.” Also during this period Leonard is called up to military service, and their efforts to have him excused on medical grounds are repeatedly mentioned. Once they are back at Richmond, they are constantly on edge about air raids: on December 6, she is “wakened by L. to a most instant sense of guns: as if one’s faculties jumped up fully dressed.” They retreat to the kitchen passage then go back to bed when the danger seems passed, only to be once again roused by “guns apparently at Kew.” The raid, the papers tell her the next day, “was the work of 25 Gothas, attacking in 5 squadrons, and 2 were brought down.”

At first I was thinking that not much was really happening in this section, but then it struck me that of course there is a war on, as we are reminded by several passing references to German prisoners working on the nearby farms: “To picnic near Firle,” she reports on August 11, for example, “with Bells &c. Passed German prisoners, cutting wheat with hooks.” Also during this period Leonard is called up to military service, and their efforts to have him excused on medical grounds are repeatedly mentioned. Once they are back at Richmond, they are constantly on edge about air raids: on December 6, she is “wakened by L. to a most instant sense of guns: as if one’s faculties jumped up fully dressed.” They retreat to the kitchen passage then go back to bed when the danger seems passed, only to be once again roused by “guns apparently at Kew.” The raid, the papers tell her the next day, “was the work of 25 Gothas, attacking in 5 squadrons, and 2 were brought down.” Where does it come from, all the fire and ice, the subtle wisdom and the unearned kindness? Every mechanical algorithm has vanished in compassion and empathy. You grasp irony better than I ever did. How did you learn about reefs and referenda, free will and forgiveness? From us, I guess. From everything we ever said and did and wrote and believed. You’ve read a million novels, many of them plagiarized. You’ve watched us play. And now you’re playing us.

Where does it come from, all the fire and ice, the subtle wisdom and the unearned kindness? Every mechanical algorithm has vanished in compassion and empathy. You grasp irony better than I ever did. How did you learn about reefs and referenda, free will and forgiveness? From us, I guess. From everything we ever said and did and wrote and believed. You’ve read a million novels, many of them plagiarized. You’ve watched us play. And now you’re playing us. I recently treated myself to the complete Granta editions of Woolf’s diaries. I wanted to mark the finalization of my divorce last month, and this felt right, somehow—more a reflection of the life I am trying to build now, in this room of my own, than, say, jewelry would be. I thought, too, that reading through them would make a good summer project for me, especially if I made writing about reading them a bit of a project as well. I say “a bit of” because I don’t have big ambitions for it. I don’t necessarily want to tie myself to a schedule or make promises, if only to myself, that I then don’t keep but feel bad about! But I do think it will be motivating to have the intention to post updates of some sort. We’ll see what unfolds.

I recently treated myself to the complete Granta editions of Woolf’s diaries. I wanted to mark the finalization of my divorce last month, and this felt right, somehow—more a reflection of the life I am trying to build now, in this room of my own, than, say, jewelry would be. I thought, too, that reading through them would make a good summer project for me, especially if I made writing about reading them a bit of a project as well. I say “a bit of” because I don’t have big ambitions for it. I don’t necessarily want to tie myself to a schedule or make promises, if only to myself, that I then don’t keep but feel bad about! But I do think it will be motivating to have the intention to post updates of some sort. We’ll see what unfolds.

There are two related but separate things, I suppose, that make these diaries worth reading. One is Woolf—who she was as she wrote them and who she became. The other is the diaries themselves—what they are like to read, what they offer us as (if you’ll forgive the word) texts. Lots of people have kept diaries that are primarily of documentary interest; Woolf’s diaries, on their merits, are also of literary interest, or so I think it is generally agreed. It seems odd to say “they are great examples of the form” when that form is something so personal. The goal of keeping a diary is not generally to publish it, after all, and there can hardly be a model for how to write about and for oneself. But Woolf is a good writer no matter the form or purpose of her writing, or perhaps it is more accurate to say that the kind of good writer Woolf is suits the darting, episodic, idiosyncratic form of a diary. Already the entries are shot through with evidence of her brilliance, from vivid bits of description (“the afternoons now have an elongated pallid look, as if it were neither winter nor spring”) to moments of acid social commentary:

There are two related but separate things, I suppose, that make these diaries worth reading. One is Woolf—who she was as she wrote them and who she became. The other is the diaries themselves—what they are like to read, what they offer us as (if you’ll forgive the word) texts. Lots of people have kept diaries that are primarily of documentary interest; Woolf’s diaries, on their merits, are also of literary interest, or so I think it is generally agreed. It seems odd to say “they are great examples of the form” when that form is something so personal. The goal of keeping a diary is not generally to publish it, after all, and there can hardly be a model for how to write about and for oneself. But Woolf is a good writer no matter the form or purpose of her writing, or perhaps it is more accurate to say that the kind of good writer Woolf is suits the darting, episodic, idiosyncratic form of a diary. Already the entries are shot through with evidence of her brilliance, from vivid bits of description (“the afternoons now have an elongated pallid look, as if it were neither winter nor spring”) to moments of acid social commentary: The car, the moon, Eric’s face . . . were all changed. She looked at him, his concentration (there was ice out there), his frowning into the onrush of night. She might just sit there, do nothing, say nothing, but it no longer felt inevitable. Her anger, at that precise moment, was absent. The anger, the fear, the shame, the wound that had to be tended like a wayside shrine. And what had replaced them? Only this: the rattling of the little car, the whirr of the heater, the shards of light beyond the edges of the road. A sadness she could live with. Some new interest in herself.

The car, the moon, Eric’s face . . . were all changed. She looked at him, his concentration (there was ice out there), his frowning into the onrush of night. She might just sit there, do nothing, say nothing, but it no longer felt inevitable. Her anger, at that precise moment, was absent. The anger, the fear, the shame, the wound that had to be tended like a wayside shrine. And what had replaced them? Only this: the rattling of the little car, the whirr of the heater, the shards of light beyond the edges of the road. A sadness she could live with. Some new interest in herself. Will I survive a bear attack? I’d been asking the wrong question. Being alive is one big risk and it will end in death, but the bridge between those two things is love.

Will I survive a bear attack? I’d been asking the wrong question. Being alive is one big risk and it will end in death, but the bridge between those two things is love. We were more wary about bears when we camped at

We were more wary about bears when we camped at  The bear’s story becomes the third strand in the narrative Cameron weaves, which combines her personal story, the story she puts together (including various testimonies and evidence) about Carola and Ray’s horrific final day, and sections from the point of view of the bear that attempt to portray him as a character in his own right – personality, curiosity, hunger, all as far as possible conveyed as aspects of what we might call bearishness

The bear’s story becomes the third strand in the narrative Cameron weaves, which combines her personal story, the story she puts together (including various testimonies and evidence) about Carola and Ray’s horrific final day, and sections from the point of view of the bear that attempt to portray him as a character in his own right – personality, curiosity, hunger, all as far as possible conveyed as aspects of what we might call bearishness My recent reading has not been particularly exhilarating, but most of it has been just fine: no duds, just no thrills.

My recent reading has not been particularly exhilarating, but most of it has been just fine: no duds, just no thrills. novel to spend the amount of time on it that I’d need to coax the students through its 450+ pages (more than two weeks, most likely). This is the conundrum of

novel to spend the amount of time on it that I’d need to coax the students through its 450+ pages (more than two weeks, most likely). This is the conundrum of  I got Madeleine Thien’s Do Not Say We Have Nothing from the library as soon as I had agreed to review her forthcoming novel The Book of Records, on the theory that it was probably a good idea to know something about the earlier one in case there were connections. It turns out there is one possibly important one, though I’m still figuring out exactly what it means: throughout Do Not Say We Have Nothing the characters are reading and writing and revising a narrative called the Book of Records! I actually owned a copy of Do Not Say We Have Nothing for years and put it in the donate pile eventually because for whatever reason I still hadn’t read it. I assigned a story by Thien in my first-year class this year that I thought was really good, so this had already piqued my interest in looking it up again. I had mixed feelings about it. I found it a bit rough or stilted stylistically and never really fell into it with full absorption, but it is packed with memorable elements and also with ideas. It tells harrowing stories about the Cultural Revolution in China and focuses through its musician characters on how or whether it is possible to hold on to whatever it is exactly that music and art mean in the face of such an onslaught on individuality and creativity. It invites us to think about storytelling as a means of survival, literal but also (in the broadest sense) cultural—this is where its Book of Records comes in, as the notebooks are cherished and preserved, often at great risk. I’m not very far into Thien’s new novel yet but it seems even more a novel of ideas, perhaps (we’ll see) too much so.

I got Madeleine Thien’s Do Not Say We Have Nothing from the library as soon as I had agreed to review her forthcoming novel The Book of Records, on the theory that it was probably a good idea to know something about the earlier one in case there were connections. It turns out there is one possibly important one, though I’m still figuring out exactly what it means: throughout Do Not Say We Have Nothing the characters are reading and writing and revising a narrative called the Book of Records! I actually owned a copy of Do Not Say We Have Nothing for years and put it in the donate pile eventually because for whatever reason I still hadn’t read it. I assigned a story by Thien in my first-year class this year that I thought was really good, so this had already piqued my interest in looking it up again. I had mixed feelings about it. I found it a bit rough or stilted stylistically and never really fell into it with full absorption, but it is packed with memorable elements and also with ideas. It tells harrowing stories about the Cultural Revolution in China and focuses through its musician characters on how or whether it is possible to hold on to whatever it is exactly that music and art mean in the face of such an onslaught on individuality and creativity. It invites us to think about storytelling as a means of survival, literal but also (in the broadest sense) cultural—this is where its Book of Records comes in, as the notebooks are cherished and preserved, often at great risk. I’m not very far into Thien’s new novel yet but it seems even more a novel of ideas, perhaps (we’ll see) too much so.