It has been a somewhat chaotic time in my classes since I last posted—not in the classes themselves, really, which have gone on much as usual, when they have actually met. But there have been a couple of unanticipated disruptions to the term, as a result of which it feels as if we are struggling to build up any momentum.

It has been a somewhat chaotic time in my classes since I last posted—not in the classes themselves, really, which have gone on much as usual, when they have actually met. But there have been a couple of unanticipated disruptions to the term, as a result of which it feels as if we are struggling to build up any momentum.

First, Queen Elizabeth died. I did not expect this to affect my class schedule at all, but when the day of her funeral was declared a provincial holiday, Dalhousie decided to follow suit, so all classes were cancelled that day. I was not in favor of this plan: it’s embarrassing enough that we still have a hereditary monarchy in the first place, and the university doesn’t close for every non-statutory holiday (we are business as usual on Easter Monday, for example). A lot of other folks still had to work that day, too. However, once the public schools were closing there were certainly pragmatic arguments for making parents’ lives easier, and although it was a pain having to revise course plans with so little notice, once I’d done that I decided just to embrace the extra day off.

When I announced the schedule changes for the “day of mourning,” I commented “Let’s just hope we don’t also have a hurricane!” Well, what do you know: Hurricane Fiona headed straight for us this past weekend, and classes are cancelled again today, as crews clean up the debris and work on restoring power. The storm was not as severe in Halifax as in other parts of the region, where it did really catastrophic damage. Other parts of the city also fared worse than we did in our particular corner, where there were lots of limbs and branches blown off and some trees sheared in two, but no huge trees or poles down. We lost power for about 38 hours; we got it back last night and then lost it again for a short time this afternoon, meaning we are definitely not taking it for granted! Our freezer packs did a decent job keeping the food in the fridge chilled, and luckily the freezer itself wasn’t packed and what was in it stayed pretty much frozen solid. We have a small camp stove we use to boil water and do a bit of cooking as needed. Increasingly, folks around us have generators, and more than one neighbor kindly offered us whatever help we needed; if the outage had gone on much longer, we would have taken them up on it gratefully.

When I announced the schedule changes for the “day of mourning,” I commented “Let’s just hope we don’t also have a hurricane!” Well, what do you know: Hurricane Fiona headed straight for us this past weekend, and classes are cancelled again today, as crews clean up the debris and work on restoring power. The storm was not as severe in Halifax as in other parts of the region, where it did really catastrophic damage. Other parts of the city also fared worse than we did in our particular corner, where there were lots of limbs and branches blown off and some trees sheared in two, but no huge trees or poles down. We lost power for about 38 hours; we got it back last night and then lost it again for a short time this afternoon, meaning we are definitely not taking it for granted! Our freezer packs did a decent job keeping the food in the fridge chilled, and luckily the freezer itself wasn’t packed and what was in it stayed pretty much frozen solid. We have a small camp stove we use to boil water and do a bit of cooking as needed. Increasingly, folks around us have generators, and more than one neighbor kindly offered us whatever help we needed; if the outage had gone on much longer, we would have taken them up on it gratefully.

Assuming we are back on Wednesday, that will actually be our only day of classes this week, as Friday is another day off, although this time deliberately so, in recognition of National Truth & Reconciliation Day.

In between these disruptions, we have actually met a few times and I think it has gone basically fine. The energy seems a bit low to me in 19th-Century Fiction, although I blame it partly on our dreary windowless room, and it’s also possible that it seems that way to me because I can’t see students’ faces. I’ve been encouraging them to nod at me the way Wemmick nods at the Aged:

In between these disruptions, we have actually met a few times and I think it has gone basically fine. The energy seems a bit low to me in 19th-Century Fiction, although I blame it partly on our dreary windowless room, and it’s also possible that it seems that way to me because I can’t see students’ faces. I’ve been encouraging them to nod at me the way Wemmick nods at the Aged:

“Here’s Mr. Pip, aged parent,” said Wemmick, “and I wish you could hear his name. Nod away at him, Mr. Pip; that’s what he likes. Nod away at him, if you please, like winking!”

“This is a fine place of my son’s, sir,” cried the old man, while I nodded as hard as I possibly could. “This is a pretty pleasure-ground, sir. This spot and these beautiful works upon it ought to be kept together by the Nation, after my son’s time, for the people’s enjoyment.”

“You’re as proud of it as Punch; ain’t you, Aged?” said Wemmick, contemplating the old man, with his hard face really softened; “there’s a nod for you;” giving him a tremendous one; “there’s another for you;” giving him a still more tremendous one; “you like that, don’t you? If you’re not tired, Mr. Pip—though I know it’s tiring to strangers—will you tip him one more? You can’t think how it pleases him.”

I tipped him several more, and he was in great spirits.

I have wondered if stretching out our time on each book (which I did because of the advice we keep getting to ease up on students because of, well, everything) might be backfiring, because we’ve been talking about the same book for so long now. On the other hand, my competing fear is that a lot of them are quite behind in the reading, which could suggest I’m not allowing enough time. Well, we’ll be done with Great Expectations this week, one way or another, and next week we start Lady Audley’s Secret, which (if previous years are any indication) will perk them up, with its lurid and fast-moving plot and utter lack of subtlety (albeit it plenty of ambiguity, some of it, IMHO, evidence of authorial ineptness, not artistic complexity). (I do enjoy the novel a lot, and wrote an appreciation of it years ago for Open Letters Monthly.)

We’ve finished with Agatha Christie already in Mystery & Detective Fiction. I used to allot two class hours to Miss Marple stories, but for all Christie’s significance to the genre, I honestly don’t find there’s all that much to say about them, so I don’t regret having trimmed away one of those hours this year. We had a good student presentation on her, which gave us a productive second round of discussion. On Friday we had our first hour on Nancy Drew; we’re losing an hour on her to Fiona but will get another chance on Wednesday, with another student presentation. I always enjoy these so much: the students are so smart and creative and engaged, and they come up with such good ideas for class activities. Overall the energy in this seminar started off pretty good and seems to be getting better: spirits were high on Friday, partly because Nancy always proves very provocative. She’s just so good, and so good at everything: it’s annoying, I agree!

We’ve finished with Agatha Christie already in Mystery & Detective Fiction. I used to allot two class hours to Miss Marple stories, but for all Christie’s significance to the genre, I honestly don’t find there’s all that much to say about them, so I don’t regret having trimmed away one of those hours this year. We had a good student presentation on her, which gave us a productive second round of discussion. On Friday we had our first hour on Nancy Drew; we’re losing an hour on her to Fiona but will get another chance on Wednesday, with another student presentation. I always enjoy these so much: the students are so smart and creative and engaged, and they come up with such good ideas for class activities. Overall the energy in this seminar started off pretty good and seems to be getting better: spirits were high on Friday, partly because Nancy always proves very provocative. She’s just so good, and so good at everything: it’s annoying, I agree!

Personally, I continue to feel somewhat disoriented and unfocused, and I’m struggling to find my rhythm and pace in the classroom, especially (to my surprise, as it has long been my favorite lecture course) in 19th-Century Fiction. I don’t think (I certainly hope!) that this wavering isn’t evident to my students—that as far as they can tell, I’ve got my head in the game. I did mention to my seminar, in the context of one confusion I fell into, that (without going into details) I wasn’t as on top of things this term as I usually expect to be and that they should just ask or set me straight if they notice me getting something wrong. These recent cancellations and the last-minute changes they have required to my carefully laid plans are not helping: I don’t enjoy uncertainty at the best of times, which these definitely are not. Here’s hoping that once Fiona is well behind us, we don’t get any more unpleasant surprises for a while.

My classes have been meeting for a week now, and I said I was going to try to get back in the habit of reflecting on them, so here I am, although to be honest I find myself at something of a loss about what to say. Should I just focus on the classroom time, on what we’re reading and talking about, as if it’s just another year? Or should I try to explain how surreal it feels to be in the classroom, talking about our readings as if it’s just another year, and then, when the time is up, to be back in the strange disordered world of grief?

My classes have been meeting for a week now, and I said I was going to try to get back in the habit of reflecting on them, so here I am, although to be honest I find myself at something of a loss about what to say. Should I just focus on the classroom time, on what we’re reading and talking about, as if it’s just another year? Or should I try to explain how surreal it feels to be in the classroom, talking about our readings as if it’s just another year, and then, when the time is up, to be back in the strange disordered world of grief?

In Women and Detective Fiction I also began with some broad overviews, of detective fiction as a genre and of some of the questions that organize the course and will frame our readings. For last class we read a handful of “classic” stories to serve as touchstones for the resisting or subversive versions to come: “The Purloined Letter,” “A Scandal in Bohemia,” and, as a sample of hard-boiled detection, Hammett’s “Death & Company,” which is one of his ‘Continental Op’ stories. These give us a good sense of the masculine milieu of so much classic detective fiction, of the habits and practices of their detectives, and of the reductive roles assigned to women, or assumed of the women, in them. Today, as a contrast, we discussed Baroness Orczy’s “The Woman in the Big Hat,” which is one of her stories about Lady Molly of Scotland Yard. It has a delightful “reveal”:

In Women and Detective Fiction I also began with some broad overviews, of detective fiction as a genre and of some of the questions that organize the course and will frame our readings. For last class we read a handful of “classic” stories to serve as touchstones for the resisting or subversive versions to come: “The Purloined Letter,” “A Scandal in Bohemia,” and, as a sample of hard-boiled detection, Hammett’s “Death & Company,” which is one of his ‘Continental Op’ stories. These give us a good sense of the masculine milieu of so much classic detective fiction, of the habits and practices of their detectives, and of the reductive roles assigned to women, or assumed of the women, in them. Today, as a contrast, we discussed Baroness Orczy’s “The Woman in the Big Hat,” which is one of her stories about Lady Molly of Scotland Yard. It has a delightful “reveal”: We had already talked about Sherlock Holmes’s condescending remark, “You see, but you do not observe!” and now we could revisit it with observations about how gender affects what you see, or what you understand about what you see, and about kinds of expertise that are typically devalued because they are women’s and therefore considered trivial. This issue was also key to our other reading for today, Susan Glaspell’s “A Jury of Her Peers,” a wonderful story that highlights the way the law fails women, making justice something that can only be achieved by subverting it. We talked about the way Glaspell’s story, instead of offering up a big reveal at the end by the superior figure of the detective, instead allows the story to unfold gradually, the women’s dawning awareness drawing us along with them as our sympathies shift from the murdered man to the woman whose happiness he destroyed. Their solidarity grows partly in reaction to the men, who are lumbering around doing more typical (but, we easily see, entirely misguided) kinds of investigating. Every time they come in and make their jovially condescending remarks about “the ladies,” we too close ranks against them:

We had already talked about Sherlock Holmes’s condescending remark, “You see, but you do not observe!” and now we could revisit it with observations about how gender affects what you see, or what you understand about what you see, and about kinds of expertise that are typically devalued because they are women’s and therefore considered trivial. This issue was also key to our other reading for today, Susan Glaspell’s “A Jury of Her Peers,” a wonderful story that highlights the way the law fails women, making justice something that can only be achieved by subverting it. We talked about the way Glaspell’s story, instead of offering up a big reveal at the end by the superior figure of the detective, instead allows the story to unfold gradually, the women’s dawning awareness drawing us along with them as our sympathies shift from the murdered man to the woman whose happiness he destroyed. Their solidarity grows partly in reaction to the men, who are lumbering around doing more typical (but, we easily see, entirely misguided) kinds of investigating. Every time they come in and make their jovially condescending remarks about “the ladies,” we too close ranks against them: Other than the masks, nothing about teaching has changed, as far as I can tell, and in the moment I find I still enjoy the things I have always enjoyed about it: the material, the students, the dynamics and demands of discussion. I am relieved that (a few minor hiccups aside) I seem to staying on top of things in spite of being tired, distracted, and out of practice. When I’m not teaching, though, or busy with the other ever-proliferating work of the term, I feel more, not less, disoriented with the difference between the sameness of it all and my new changed reality. It’s a good thing, I know, that I am able to show up and be (more or less) my old self in the classroom, but at the same time I don’t know how to make sense of that or be at ease with it.

Other than the masks, nothing about teaching has changed, as far as I can tell, and in the moment I find I still enjoy the things I have always enjoyed about it: the material, the students, the dynamics and demands of discussion. I am relieved that (a few minor hiccups aside) I seem to staying on top of things in spite of being tired, distracted, and out of practice. When I’m not teaching, though, or busy with the other ever-proliferating work of the term, I feel more, not less, disoriented with the difference between the sameness of it all and my new changed reality. It’s a good thing, I know, that I am able to show up and be (more or less) my old self in the classroom, but at the same time I don’t know how to make sense of that or be at ease with it.

If my book club hadn’t settled on Sea of Tranquility for our next read, I don’t think I would have read it, not because I haven’t liked the other novels I’ve read by Emily St. John Mandel, because I’ve liked them just fine (

If my book club hadn’t settled on Sea of Tranquility for our next read, I don’t think I would have read it, not because I haven’t liked the other novels I’ve read by Emily St. John Mandel, because I’ve liked them just fine ( There’s real cleverness to the novel’s time-travel plot (though I don’t think these can ever be completely convincing), and a poignancy to the human story threaded through it, and the ongoing theme of pandemics created both menace in the moment and resonance for our moment.

There’s real cleverness to the novel’s time-travel plot (though I don’t think these can ever be completely convincing), and a poignancy to the human story threaded through it, and the ongoing theme of pandemics created both menace in the moment and resonance for our moment.  The other key idea in Sea of Tranquility seems to be “if you have the chance to save someone’s life, you should do it, rules or consequences be damned.” This hardly seems like a big idea—in fact, it seems trite, a point hardly worth making, a choice so obvious it hardly counts as heroism . . . except that for Gaspery, the rules are made by vast and powerful institutions and the consequences are literally historic. Does that make the “right” choice any less obvious? A different novelist, or a different kind of novel, would have made more of this, of how we weigh the kindness to others that defines our humanity against our own needs and vulnerabilities, and also against larger goals and values that might be incompatible with it and yet still, possibly, worth serving. “We should be kind,”

The other key idea in Sea of Tranquility seems to be “if you have the chance to save someone’s life, you should do it, rules or consequences be damned.” This hardly seems like a big idea—in fact, it seems trite, a point hardly worth making, a choice so obvious it hardly counts as heroism . . . except that for Gaspery, the rules are made by vast and powerful institutions and the consequences are literally historic. Does that make the “right” choice any less obvious? A different novelist, or a different kind of novel, would have made more of this, of how we weigh the kindness to others that defines our humanity against our own needs and vulnerabilities, and also against larger goals and values that might be incompatible with it and yet still, possibly, worth serving. “We should be kind,”  My copy of Never Let Me Go is a 2006 edition, and it may well have been in 2006 that I read it for the first time. I’ve tried several times since then to reread it. The Remains of the Day is one of my personal top 10 novels: I consider it pretty much perfect. Many people I know admire Never Let Me Go even more, so it has always seemed that it would be worth going back to, both to experience it in that fuller way you usually can on a rereading and to see if I might like to assign it some day. And yet I have never read it again until now—at least, not all the way through. Why? Because every time I have tried, I have found it too dull, too slow, too (to put a more positive spin on it) subtle. Subtlety is one of Ishiguro’s great gifts, of course, but his characteristic understatement actually demands a lot of his readers en route to its rewards, and on every other attempt I just couldn’t keep it up.

My copy of Never Let Me Go is a 2006 edition, and it may well have been in 2006 that I read it for the first time. I’ve tried several times since then to reread it. The Remains of the Day is one of my personal top 10 novels: I consider it pretty much perfect. Many people I know admire Never Let Me Go even more, so it has always seemed that it would be worth going back to, both to experience it in that fuller way you usually can on a rereading and to see if I might like to assign it some day. And yet I have never read it again until now—at least, not all the way through. Why? Because every time I have tried, I have found it too dull, too slow, too (to put a more positive spin on it) subtle. Subtlety is one of Ishiguro’s great gifts, of course, but his characteristic understatement actually demands a lot of his readers en route to its rewards, and on every other attempt I just couldn’t keep it up.

The novel’s thought experiment about cloning is chilling and provocative in the questions it raises about where scientific or medical “advances” might take us. I think it’s more powerful, though, as a commentary on meaning and value in our own lives, which also end in death sentences, if usually of a less calculated kind. Why would reading Daniel Deronda be pointless for Kathy and not for me? Why all these lessons, all these books and discussions? Why do we do all of this work? Some novels (I’m thinking of

The novel’s thought experiment about cloning is chilling and provocative in the questions it raises about where scientific or medical “advances” might take us. I think it’s more powerful, though, as a commentary on meaning and value in our own lives, which also end in death sentences, if usually of a less calculated kind. Why would reading Daniel Deronda be pointless for Kathy and not for me? Why all these lessons, all these books and discussions? Why do we do all of this work? Some novels (I’m thinking of  Phyllis felt after this meeting with Nicky that she had crossed a line, like being on board a ship where there were certain ceremonies for when you crossed the Equator. It wasn’t only that Nicky spoke as if they might go out together and she could meet his friends, gain entry to a whole new world of social relations. It was that she knew nothing about this world of his. Everything she’d ever known had been nothing: she might as well scrape away all the things she’d taken for granted all her life, to begin again. She seemed to watch herself undressing, in that room of Nicky’s with no accretions of furniture or domesticity, dropping the pieces of her clothing one by one onto the bare floorboards, leaving her old self behind, climbing into his bed, weightless and transparent as a naked soul in an old painting.

Phyllis felt after this meeting with Nicky that she had crossed a line, like being on board a ship where there were certain ceremonies for when you crossed the Equator. It wasn’t only that Nicky spoke as if they might go out together and she could meet his friends, gain entry to a whole new world of social relations. It was that she knew nothing about this world of his. Everything she’d ever known had been nothing: she might as well scrape away all the things she’d taken for granted all her life, to begin again. She seemed to watch herself undressing, in that room of Nicky’s with no accretions of furniture or domesticity, dropping the pieces of her clothing one by one onto the bare floorboards, leaving her old self behind, climbing into his bed, weightless and transparent as a naked soul in an old painting. The novel turns on a dramatic act of rebellion: suburban housewife Phyllis leaves her home, husband, and children to move in with her lover (who, spoiler alert, turns out—in what felt like a completely unnecessary plot wrinkle—to be her husband’s son by another woman). It’s a decision that should have felt weighty, dramatic, consequential, but it did not feel well motivated: it’s impulsive, and it’s only after the fact that Phyllis really begins to understand the social upheavals that she asserts interest in. If she has an epiphany, it’s an unconvincing one, and (maybe this is just my Victorian moralist showing up) yet Phyllis ups and walks away from people who love and need her, as if duty doesn’t mean anything in the face of desire. I found her both uninteresting and unsympathetic, a bad combination, and the novel just presents her, so I was never really sure whether I was supposed to feel differently.

The novel turns on a dramatic act of rebellion: suburban housewife Phyllis leaves her home, husband, and children to move in with her lover (who, spoiler alert, turns out—in what felt like a completely unnecessary plot wrinkle—to be her husband’s son by another woman). It’s a decision that should have felt weighty, dramatic, consequential, but it did not feel well motivated: it’s impulsive, and it’s only after the fact that Phyllis really begins to understand the social upheavals that she asserts interest in. If she has an epiphany, it’s an unconvincing one, and (maybe this is just my Victorian moralist showing up) yet Phyllis ups and walks away from people who love and need her, as if duty doesn’t mean anything in the face of desire. I found her both uninteresting and unsympathetic, a bad combination, and the novel just presents her, so I was never really sure whether I was supposed to feel differently. The vast metaphor which most faithfully represents this fathomless ordeal . . . is that of Dante, and his all-too-familiar lines still arrest the imagination with their augury of the unknowable, the black struggle to come:

The vast metaphor which most faithfully represents this fathomless ordeal . . . is that of Dante, and his all-too-familiar lines still arrest the imagination with their augury of the unknowable, the black struggle to come: I read Darkness Visible on the recommendation of a friend who knew that I have been struggling to understand Owen’s decision to end his life from his point of view, not just because he did not share many details of his struggle but because I have never experienced depression myself—sadness, yes, and now grief, but these are far from the same thing.

I read Darkness Visible on the recommendation of a friend who knew that I have been struggling to understand Owen’s decision to end his life from his point of view, not just because he did not share many details of his struggle but because I have never experienced depression myself—sadness, yes, and now grief, but these are far from the same thing. Styron dislikes the term “depression”: “melancholia,” he thinks, “would still appear to be a far more apt and evocative word for the blacker forms of the disorder,” whereas “depression,” bland and innocuous sounding, inhibits understanding “of the horrible intensity of the disease when out of control.” Styron carefully chronicles his own descent into the worst of it, frankly examining the role of his drinking (which he believes actually held the depression at bay for some time), the onset of “a kind of numbness” in which his own body began to feel unfamiliar to him, and then a pattern of “anxiety, agitation, unfocused dread” leading to “a suffocating gloom” and “an immense and aching solitude.” He recounts the medications he took (this was before the widespread use of today’s most frequently prescribed antidepressants), the therapy he finally sought out, and his eventual hospitalization, which in his case proved life-saving, mostly because (as he tells it) it bought him precious time:

Styron dislikes the term “depression”: “melancholia,” he thinks, “would still appear to be a far more apt and evocative word for the blacker forms of the disorder,” whereas “depression,” bland and innocuous sounding, inhibits understanding “of the horrible intensity of the disease when out of control.” Styron carefully chronicles his own descent into the worst of it, frankly examining the role of his drinking (which he believes actually held the depression at bay for some time), the onset of “a kind of numbness” in which his own body began to feel unfamiliar to him, and then a pattern of “anxiety, agitation, unfocused dread” leading to “a suffocating gloom” and “an immense and aching solitude.” He recounts the medications he took (this was before the widespread use of today’s most frequently prescribed antidepressants), the therapy he finally sought out, and his eventual hospitalization, which in his case proved life-saving, mostly because (as he tells it) it bought him precious time: Not always, of course, and as a book like this can only be written by just such a survivor, it is bound to tilt more towards optimism than might in other cases seem warranted. From his own experience, Styron appreciates that convincing a depressed person (usually “in a state of unrealistic hopelessness”) to see things as he now does is “a tough job”:

Not always, of course, and as a book like this can only be written by just such a survivor, it is bound to tilt more towards optimism than might in other cases seem warranted. From his own experience, Styron appreciates that convincing a depressed person (usually “in a state of unrealistic hopelessness”) to see things as he now does is “a tough job”: True to his own experience, though, Styron does not end on this gloomy note, but on a more uplifting one:

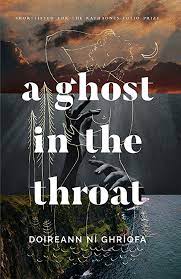

True to his own experience, though, Styron does not end on this gloomy note, but on a more uplifting one: July was not a very good reading month for me. By habit and on principle I usually finish most of the books I start, at least if I have any reason to think they are worth a bit of effort if it’s needed. In July, however, I not only didn’t even start many books (not by my usual standards, anyway) but I set aside almost as many books as I completed—Bloomsbury Girls (which hit all my sweet spots in theory but fell painfully flat in practice), Gilead (a reread I was enthusiastic about at first but just could not persist with), A Ghost in the Throat (which I will try again, as I liked its voice—what I struggled with was its essentialism and its somewhat miscellaneous or wandering structure). I already mentioned Andrew Miller’s Oxygen and Monica Ali’s Love Marriage, both of which I finished and enjoyed,

July was not a very good reading month for me. By habit and on principle I usually finish most of the books I start, at least if I have any reason to think they are worth a bit of effort if it’s needed. In July, however, I not only didn’t even start many books (not by my usual standards, anyway) but I set aside almost as many books as I completed—Bloomsbury Girls (which hit all my sweet spots in theory but fell painfully flat in practice), Gilead (a reread I was enthusiastic about at first but just could not persist with), A Ghost in the Throat (which I will try again, as I liked its voice—what I struggled with was its essentialism and its somewhat miscellaneous or wandering structure). I already mentioned Andrew Miller’s Oxygen and Monica Ali’s Love Marriage, both of which I finished and enjoyed,  Ali Smith’s how to be both was a mixed experience for me. My copy began with the contemporary story (as you may know, two versions were published), and it read easily for me and was quite engaging, in the same way that the

Ali Smith’s how to be both was a mixed experience for me. My copy began with the contemporary story (as you may know, two versions were published), and it read easily for me and was quite engaging, in the same way that the  Another reread for me in July was Yiyun Li’s

Another reread for me in July was Yiyun Li’s  No, it’s not an elegy, I thought. No parent should write a child’s elegy.

No, it’s not an elegy, I thought. No parent should write a child’s elegy. July 2019

July 2019