I love Steve’s series on his readings in the “Penny Press.” He engages with such gusto with all kinds of periodicals, from highbrow literary journals to lad mags to Dogfancy and National Geographic–and he’s so delighted when he finds good stuff, and so disheartened when his favorites let him down.

Reading Steve’s posts always makes me think about the magazines I read. It’s a small number: I do most of my more miscellaneous reading online, and the only print periodical I actually have a current subscription to is the New York Review of Books (some years it’s the TLS instead, but next year I think it will be the NYRB again, and/or the London Review of Books). I do pick up individual issues of magazines sometimes–but they are almost never literary, culture, or news magazines. Usually, they are quilting magazines, with the occasional foray into Canadian Living (which I did subscribe to for many years–for the recipes!) and a dip into the Running Room’s freebie whenever I pass by the store. Once in a while I pick out something else for variety: I bought Granta‘s spring feminism issue, for instance, but I’m at least as likely to bring home something like the issue of Piecework shown in the photo.

Reading Steve’s posts always makes me think about the magazines I read. It’s a small number: I do most of my more miscellaneous reading online, and the only print periodical I actually have a current subscription to is the New York Review of Books (some years it’s the TLS instead, but next year I think it will be the NYRB again, and/or the London Review of Books). I do pick up individual issues of magazines sometimes–but they are almost never literary, culture, or news magazines. Usually, they are quilting magazines, with the occasional foray into Canadian Living (which I did subscribe to for many years–for the recipes!) and a dip into the Running Room’s freebie whenever I pass by the store. Once in a while I pick out something else for variety: I bought Granta‘s spring feminism issue, for instance, but I’m at least as likely to bring home something like the issue of Piecework shown in the photo.

I’ve been wondering why it is that these are the choices I make from the magazine rack and not, say, Harper’s or the New Yorker (or The Walrus, for that matter). What is the lure of these publications dedicated to food, fabrics, and healthy living? These are hardly the central concerns of my days, or at least, not so much that you’d think I would want pages and pages of articles about and glossy colour photographs of them. That said, I do dabble in all of these things: by and large I’m the family chef, and I appreciate getting new menu ideas; I do a little quilting and needlework; and I’ve been a slow, intermittent, but fairlypersistent runner since my “Learn to Run” clinic several years ago. Do you suppose that I buy these magazines because I wish these activities were a bigger part of my life? Do I buy them because doing so gives me the illusion that I do more of this stuff than I actually do–is browsing their pages a way of pretending I’m the sort of person who might run a marathon some day and distributes full-sized quilts to friends and family that have all the points of their triangle patches all neatly in position?

I do think that is part of why I buy them: to bolster my sense of commitment to things that are actually (partly by choice, partly by pragmatic necessity) peripheral to my main priorities. But why would I wish I were living the life that these magazines collectively illustrate, rather than the life I do in fact live? Why is my magazine pile not all book reviews–not to mention academic journals (which I read only under duress now)? Thinking about what the magazines I like have in common, I noticed that they all emphasize two things: the individual satisfaction of tangible achievements (something rare in academic work), and a strong sense of community created by a shared passion. The Running Room magazine and the quilting ones I like are especially conspicuous for their stories of people helping each other to realize their dreams: the Running Room has tributes to clinic leaders and coaches who inspired runners to do more than they thought possible, of people who began just as members of the same running groups and became fast friends. I love the “shop hop” issues of Quilt Sampler, which feature different shops around the country (sometimes in Canada, too) with stories of how they were founded, often by a couple or a pair or group of friends who just really wanted to shape their lives around something they loved and, happily, found a community of like-minded customers and became a supportive, creative community. I think I pore over these stories because academic work is only intermittently like that: the work itself, in fact, often seems to pull us (or at least me) away from the kind of creative fulfilment and warm-heartedness the quilt shop owners seem to enjoy in their work lives. Also, on a more personal level, I’m often a bit lonely in my day-to-day life: my extended family is all far away, my local friends are as busy and stressed out as I am, if not more; a lot of my work is done in solitude, and its group aspects are far from warm-hearted and creative (committee meetings, anyone?)–it’s easy to feel isolated, and the world these magazines conjure (and this is true of Canadian Living as well) is not like that. So, they represent a kind of fantasy life for me, in a few variations, one that if I had more time and energy and guts I might be able to pursue here (I could take a quilting class, maybe–but the nearest quilting store is quite far away, and winter is coming, with its icy roads… I could take another Running Room clinic–but they are often in the evenings, and I’m just so tired and swamped…and again, winter’s coming). Also, in my fantasy life I really love to cook, and nobody in the house has food allergies or any other dietary complications…

There’s one other thing I know I buy the quilting and needlework magazines for: often, their pages are just beautiful! And though I don’t have (or make, I guess) a lot of time for quilting, I do get some done now and then, and it’s inspiring to look at the colours and patterns and spend a little time indulging in the sensual pleasures they offer: they are treats for the eye, just as the fabrics are when you’re actually quilting (when they are a tactile pleasure as well–I bet all quilters sort their stash once in a while really for no purpose than to fondle the fabrics and look at them some more).

(A couple of my more recent quilting efforts: “Overall Bodie” and “Blue Ocean”)

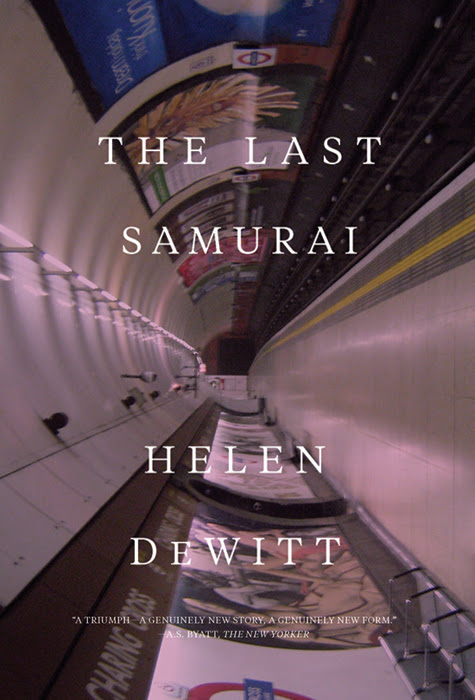

The Last Samurai

The Last Samurai This is a novel that feels exceptionally difficult (and more than usually pointless) to excerpt from–and yet, the temptation! And it incorporates so much that it’s difficult to know what to single out for commentary. One aspect of it that is obviously very important, both structurally and thematically, is its engagement with Kurosawa’s The Seven Samurai (which I have never seen–but the range of things alluded to in this novel that I don’t know first-hand is so long there’s no point remarking them all). The Seven Samurai is Sybilla’s favourite film. Not only does she watch it over and over, but she thinks of it as taking the place of a male role model in Ludo’s life. What she doesn’t expect, when she first shows it to him (when he’s five) is that it will prompt him to demand to learn Japanese.

This is a novel that feels exceptionally difficult (and more than usually pointless) to excerpt from–and yet, the temptation! And it incorporates so much that it’s difficult to know what to single out for commentary. One aspect of it that is obviously very important, both structurally and thematically, is its engagement with Kurosawa’s The Seven Samurai (which I have never seen–but the range of things alluded to in this novel that I don’t know first-hand is so long there’s no point remarking them all). The Seven Samurai is Sybilla’s favourite film. Not only does she watch it over and over, but she thinks of it as taking the place of a male role model in Ludo’s life. What she doesn’t expect, when she first shows it to him (when he’s five) is that it will prompt him to demand to learn Japanese. One of the most fascinating explorations of this in the novel is the story of the pianist Kenzo Yamamoto, who becomes obsessed, not with how to play a particular note or phrase or piece, but with how else you could play it, or how else it could sound:

One of the most fascinating explorations of this in the novel is the story of the pianist Kenzo Yamamoto, who becomes obsessed, not with how to play a particular note or phrase or piece, but with how else you could play it, or how else it could sound: Her bitterness at the inadequacies of the Circle Line riders is balanced by this moment of grace. Why do we put such limits, not just on our children, but on our art? Much, much later in the novel, Yamamoto says to Ludo, “When you play a piece of music there are so many different ways you could play it. You keep asking yourself what if. You try this and you say but what if and you try that. When you buy a CD you get one answer to the question. You never get the what if.” There’s no place for Yamamoto’s “what if” in the world of concert halls and recording studios and trains to catch.

Her bitterness at the inadequacies of the Circle Line riders is balanced by this moment of grace. Why do we put such limits, not just on our children, but on our art? Much, much later in the novel, Yamamoto says to Ludo, “When you play a piece of music there are so many different ways you could play it. You keep asking yourself what if. You try this and you say but what if and you try that. When you buy a CD you get one answer to the question. You never get the what if.” There’s no place for Yamamoto’s “what if” in the world of concert halls and recording studios and trains to catch.