I have still not deciphered the mystery of the hare. She remains the elusive, indefinable core that explains, perhaps, why we humans have projected so many of our fears and desires onto the species, investing hares with supernatural powers from the most evil to the most inviting, confirming our tendency to either worship or demonise those things we struggle to understand. The hare lends itself as a symbol of the transience of life and its fleeting glory, and our dependence on nature and our careless destruction of it. But in the hare’s—and nature’s—endless capacity for renewal, we can find hope. If it is possible, as William Blake would have it, ‘to see a world in a grain of sand’, then perhaps we can see all nature in a hare: its simplicity and intricacy, fragility and glory, transience and beauty.

I have still not deciphered the mystery of the hare. She remains the elusive, indefinable core that explains, perhaps, why we humans have projected so many of our fears and desires onto the species, investing hares with supernatural powers from the most evil to the most inviting, confirming our tendency to either worship or demonise those things we struggle to understand. The hare lends itself as a symbol of the transience of life and its fleeting glory, and our dependence on nature and our careless destruction of it. But in the hare’s—and nature’s—endless capacity for renewal, we can find hope. If it is possible, as William Blake would have it, ‘to see a world in a grain of sand’, then perhaps we can see all nature in a hare: its simplicity and intricacy, fragility and glory, transience and beauty.

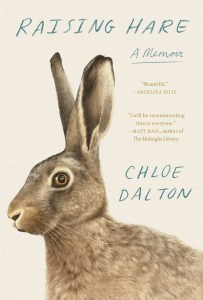

Probably the most important parts of Raising Hare, Chloe Dalton’s memoir of how she took in an abandoned leveret and, in helping it survive, found her own way to a new relationship with nature, time, and life itself, are the ones in which she turns from her immediate experience and its personal resonance to larger issues of environmentalism and conservation. “From hunting to farming and the destruction of habitats,” she observes,

we have done so much harm to hares over the centuries. For sport—in other words, for idle amusement—and in our drive for economic efficiency, putting more pressure on the land than it and its wild inhabitants can bear. The turn of the seasons and our capacity for adaptation means there is always hope that we can do things differently. But in this, as in so many areas, our practices and our methods incline towards depletion: reducing the dwindling stock of nature that remains to us, today’s needs always outweighing our aspirations for tomorrow.

Raising Hare arrives rather than begins here, though, and so rather than feeling hectoring it feels urgent: Dalton spends most of the book sharing the gradual process of her getting to know the little leveret, eventually an adult hare who gives birth to her own babies, and so we are drawn in until we are as invested in its flourishing, as interested in its mysteries, and as fearful of its possible fate as she is.

Dalton is aware from the beginning that her involvement is problematic: hares are not domesticated, and even with the best intentions, interfering with wild animals can make things worse rather than better. Still, she is unable to leave the leveret where she finds it, alone, freezing, on a track where it is vulnerable to both natural predators and vehicles. Throughout her time caring for it and then living alongside it, she does her best to let it still be wild—refusing to treat it as a pet or even to name it. She does not attempt to train it; in fact, it seems fair to say that it is the hare that trains her, over time reshaping Dalton’s habits, attitudes, and expectations. “I felt a new spirit of attentiveness to nature,” she says,

no less wonderful for being entirely unoriginal, for as old as it is as a human experience, it was new to me. For many years, the seasons had largely passed me by, my perceptions of the steady cycle of nature disrupted by travel and urban life. I had observed nature in broad brushstrokes, in primary colours, at a surface level. I had been most interested in whether it was dry enough to walk, or warm enough to eat outside with friends. I could identify only a handful of birds and trees by name. I hadn’t observed the buds unfurling, the seasonal passage of birds, the unshakeable rituals and rhythms of life in a single field or wood.

A busy professional addicted “to the adrenaline rush of responding to events and crises,” Dalton has already had her usual life disrupted by the pandemic, which has “pinned” her in the countryside, her work life shifted (as for so many of us) to hours spent at her computer. The presence of the hare brings a new element of calm into her life:

I couldn’t help but compare its serenity and steadiness to the sense of frenetic activity that had pervaded my life for years, marked by constant vigilance, unpredictability and stress.

Observing the hare’s very different existence leads her to rethink her longstanding priorities, to wonder “what else I might enjoy that I’d never considered” rather than to assume that what she wanted was “for life to go back to normal.”

It is not an idyll: lovely as Dalton’s descriptions of the fields and woods are, the hare’s world is still that of nature “red in tooth and claw,” full of hazards and threats, violence and death, hawks and stoats and foxes. The worst carnage, however, is wrought not by nature but by man’s machinery. One day a pair of huge tractors harvest potatoes from the field next door. When they are finished, Dalton walks the furrows and finds them (in a scene worthy of Thomas Hardy) littered with dead or injured hares:

It is not an idyll: lovely as Dalton’s descriptions of the fields and woods are, the hare’s world is still that of nature “red in tooth and claw,” full of hazards and threats, violence and death, hawks and stoats and foxes. The worst carnage, however, is wrought not by nature but by man’s machinery. One day a pair of huge tractors harvest potatoes from the field next door. When they are finished, Dalton walks the furrows and finds them (in a scene worthy of Thomas Hardy) littered with dead or injured hares:

I stood at the edge of the fourteen-acre field and wondered with a sinking heart how many other leverets, or indeed ground-nesting birds, had been crushed beneath those implacable wheels and now lay within the ridges or lost to sight against the rutted brown earth. It was just another day just another harvest, a scene replicated up and down the land and across the world.

By this point in the book, she has earned our companionship in her anxiety for the one particular hare she knows, which serves in turn to draw us in to her horror at the scale of destruction. Noting that the whole process was designed for one particular kind of efficiency, she asks why we cannot put our ingenuity to work to reduce the harm done:

If it is possible to create robots and drones to reap our fields for us, could we not use technology to detected the presence of leverets, and fawns, and nesting birds, and could reasonable efforts not be made to relocate them, rather than simply leaving them to be crushed beneath our machines?

I think a lot of us are asking, with growing anger as well as despair, similar questions about many of the technologies that are doing so much harm to our natural world, often without offering a compensating good anywhere near as defensible as a more abundant and affordable food supply.

Most of Raising Hare is in a different register, though, so it never feels either didactic or despairing. Dalton learns about and from the hare by observing it and sharing space with it, and eventually with some of its offspring. She writes with care and tenderness about what she sees. The animals come and go from her house (she eventually gets a ‘hare door’ built to be sure they are never confined, even when she’s not there to open or close the entrances); she comes to see the boundary between her life and theirs as similarly artificial and porous. She has to accept that it is not her place to protect them, even if she knew how; the death of one of the hare’s babies from no evident cause is a reminder of the limits of her control as well as her knowledge. It is sad, but it is also part of what it means for an animal to be wild. “My lasting memory of the little leveret,” she says, “is of a small, graceful figure, staring at the setting sun.”

One reason Raising Hare resonated with me is that over the past six months, since Freddie came to live with me, I have been experiencing on a small scale some of the same adjustments to my own sense of time and priorities. Living close to the hare helps Dalton better understand people’s bonds with their pets:

One reason Raising Hare resonated with me is that over the past six months, since Freddie came to live with me, I have been experiencing on a small scale some of the same adjustments to my own sense of time and priorities. Living close to the hare helps Dalton better understand people’s bonds with their pets:

I had come to appreciate that affection for an animal is of a different kind entirely [than for people]: untinged by the regret, complexities, and compromises of human relationships. It has an innocence and purity all its own. In the absence of verbal communication, we extend ourselves to comprehend and meet their needs and, in return, derive companionship and interest from their presence, while also steeling ourselves for inevitable pain, since their lives are for the most part much shorter than ours.

I spend a lot of time playing with Fred, and there is something so refreshingly simple about it: it’s not just that her antics often make me laugh, but that what she wants is just to play, and taking a break from my own work or chores to play with her forces me—or, to put it differently, gives me a chance—to put aside the “regrets, complexities, and compromises” and stresses and confusions and griefs that so often preoccupy me and just to be for a while. Sometimes it feels at first like an interruption, like something that takes patience, but the satisfaction of seeing her stalking and pouncing on her favourite dangly fish toy or rocketing through her tunnel always brings me around. And when she’s not playing, she’s napping, as often as possible on my lap; much like Dalton feeling inspired by the hare’s tranquility, I am calmed and soothed by Fred’s warmth and purrs. Because of her, I get up earlier now than I used to—but this means I can ease into the rest of my day, which I have come to love. I’m also very aware that while I decided to adopt her for my own reasons, now that she’s here, she has her reasons too, and she both needs and deserves my care and respect. That’s not quite the scale of revelation that comes to Dalton by way of the hare, but I think it’s related, part of the same recognition that we are, all of us, nature.

For the first time ever, I have assigned Scenes of Clerical Life in one of my classes—more accurately, a scene of clerical life, “Janet’s Repentance.” My re-reading of it some years ago had lodged the possibility of assigning the story (novella?) in my mind, but I hadn’t found what felt like the right opportunity until this term’s all-George Eliot, all the time seminar. We are discussing “Janet’s Repentance” in the seminar this week, so I thought that was a good enough reason to lift this post out of the archives.

For the first time ever, I have assigned Scenes of Clerical Life in one of my classes—more accurately, a scene of clerical life, “Janet’s Repentance.” My re-reading of it some years ago had lodged the possibility of assigning the story (novella?) in my mind, but I hadn’t found what felt like the right opportunity until this term’s all-George Eliot, all the time seminar. We are discussing “Janet’s Repentance” in the seminar this week, so I thought that was a good enough reason to lift this post out of the archives. “Do you wonder,” asks our narrator, as the sordid tale unfolds, “how it was that things had come to this pass — what offence Janet had committed in the early years of marriage to rouse the brutal hatred of this man? . . . But do not believe,” she goes on,

“Do you wonder,” asks our narrator, as the sordid tale unfolds, “how it was that things had come to this pass — what offence Janet had committed in the early years of marriage to rouse the brutal hatred of this man? . . . But do not believe,” she goes on,

Another January, another new term! I’ve got two classes this term of two quite different kinds. The first is our second-year survey course British Literature After 1800, so its aim is to cover a broad sweep of territory; the other is a combined Honours and graduate seminar on George Eliot, a rare opportunity to zoom in on a single writer—a privilege rarely accorded, in our program anyway, to anyone besides Shakespeare!

Another January, another new term! I’ve got two classes this term of two quite different kinds. The first is our second-year survey course British Literature After 1800, so its aim is to cover a broad sweep of territory; the other is a combined Honours and graduate seminar on George Eliot, a rare opportunity to zoom in on a single writer—a privilege rarely accorded, in our program anyway, to anyone besides Shakespeare! Something that was very much on my mind as I prepared for this particular class meeting was the last time I taught this course, which was the winter term of 2020. In early March of that term, we were all sent home; my notes leading up to what turned out to be our last day in person have a number of references to contingency plans, but none of them (none of us) anticipated the scale of disruption. It came on so quickly, too, as my notes remind me. We were part way through our work on Woolf’s Three Guineas on our final day; quite literally the last thing I wrote on the whiteboard was “burn it all down.” I got quite emotional many times while revising the course materials for this year’s version: that term stands out so vividly in my mind as “the before time,” before COVID, which is also, for me, before Owen died. We were still essentially in lockdown, after all, when he died in 2021; we had only just been able to start coming together as a family again. I don’t usually have a lot of emotional investment in my course materials, but it was unexpectedly difficult revisiting these and thinking of how much has changed. Tearing up over PowerPoint slides: it seemed absurd even as it happened, but it did. That said, because of COVID I ended up cutting The Remains of the Day from the syllabus in 2020, and given that it is in my personal top 10, that I rarely have the opportunity to assign relatively contemporary fiction, and that I am running out of years to assign anything at all, I am stoked about being able to read through it with my class this term. If only it didn’t feel so timely!

Something that was very much on my mind as I prepared for this particular class meeting was the last time I taught this course, which was the winter term of 2020. In early March of that term, we were all sent home; my notes leading up to what turned out to be our last day in person have a number of references to contingency plans, but none of them (none of us) anticipated the scale of disruption. It came on so quickly, too, as my notes remind me. We were part way through our work on Woolf’s Three Guineas on our final day; quite literally the last thing I wrote on the whiteboard was “burn it all down.” I got quite emotional many times while revising the course materials for this year’s version: that term stands out so vividly in my mind as “the before time,” before COVID, which is also, for me, before Owen died. We were still essentially in lockdown, after all, when he died in 2021; we had only just been able to start coming together as a family again. I don’t usually have a lot of emotional investment in my course materials, but it was unexpectedly difficult revisiting these and thinking of how much has changed. Tearing up over PowerPoint slides: it seemed absurd even as it happened, but it did. That said, because of COVID I ended up cutting The Remains of the Day from the syllabus in 2020, and given that it is in my personal top 10, that I rarely have the opportunity to assign relatively contemporary fiction, and that I am running out of years to assign anything at all, I am stoked about being able to read through it with my class this term. If only it didn’t feel so timely! I am also super stoked about getting to spend the whole term reading and talking about George Eliot with a cluster of our best students—not just our brightest but honestly, I know most of these students from other classes and they are some of the nicest and keenest and most engaged and curious people you could hope to work with. I felt so much good will from them today as we did our ice-breaker (nothing too “cringe,” just everyone’s names and anything they wanted to share about their previous experience, or lack of experience, with George Eliot). I hope their positive attitude survives Felix Holt, not to mention Daniel Deronda! Knowing that a number of them had read Adam Bede and/or Middlemarch with me in other recent courses, I left both of these off the reading list for this one. Middlemarch especially feels like a gap, but on the other hand, I don’t think I could have realistically asked them to read both Middlemarch and Daniel Deronda in the same term (unless I didn’t assign anything else), and Daniel Deronda is pretty great. I had quite a debate with myself about Felix Holt vs Romola: just for myself, I would have preferred to reread Romola, but I’ve taught Felix Holt in undergraduate courses before and it is actually pretty accessible. Sure, Felix is so wooden he makes Adam Bede look lively and nuanced, but, speaking of timely, a book about the pitfalls of democracy when the population is not (ahem) maybe sufficiently wise to make good choices seems on point. Along with those two, we will be reading “Janet’s Repentance,” The Mill on the Floss, and Silas Marner. I’m already a bit worried that it’s going to be too much reading . . .

I am also super stoked about getting to spend the whole term reading and talking about George Eliot with a cluster of our best students—not just our brightest but honestly, I know most of these students from other classes and they are some of the nicest and keenest and most engaged and curious people you could hope to work with. I felt so much good will from them today as we did our ice-breaker (nothing too “cringe,” just everyone’s names and anything they wanted to share about their previous experience, or lack of experience, with George Eliot). I hope their positive attitude survives Felix Holt, not to mention Daniel Deronda! Knowing that a number of them had read Adam Bede and/or Middlemarch with me in other recent courses, I left both of these off the reading list for this one. Middlemarch especially feels like a gap, but on the other hand, I don’t think I could have realistically asked them to read both Middlemarch and Daniel Deronda in the same term (unless I didn’t assign anything else), and Daniel Deronda is pretty great. I had quite a debate with myself about Felix Holt vs Romola: just for myself, I would have preferred to reread Romola, but I’ve taught Felix Holt in undergraduate courses before and it is actually pretty accessible. Sure, Felix is so wooden he makes Adam Bede look lively and nuanced, but, speaking of timely, a book about the pitfalls of democracy when the population is not (ahem) maybe sufficiently wise to make good choices seems on point. Along with those two, we will be reading “Janet’s Repentance,” The Mill on the Floss, and Silas Marner. I’m already a bit worried that it’s going to be too much reading . . . The last time I taught this class was 2015, and then it was a graduate seminar only. I had stepped back a bit from teaching in our graduate program: we get at most one seminar a year, and my favourite classes to teach have always been our 4th-year or honours seminars, so I made them my priority. OK, that’s not entirely truthful: I had also felt increasingly uncomfortable with graduate teaching, both because of my own loss of faith in aspects of academic research and publication (

The last time I taught this class was 2015, and then it was a graduate seminar only. I had stepped back a bit from teaching in our graduate program: we get at most one seminar a year, and my favourite classes to teach have always been our 4th-year or honours seminars, so I made them my priority. OK, that’s not entirely truthful: I had also felt increasingly uncomfortable with graduate teaching, both because of my own loss of faith in aspects of academic research and publication ( Believe it or not, I’ve been posting here about my teaching

Believe it or not, I’ve been posting here about my teaching  2025 was a less chaotic year for me—literally and psychologically—than 2024. I wish I could say that this meant I read more and better, but instead both my memory and my records show that it was a pretty uneven reading year, with a lot of slumps. The summer especially, which used to be a rich reading season for me, had almost no highlights: the best books I read in 2025 were at the very beginning and the very end of the year.

2025 was a less chaotic year for me—literally and psychologically—than 2024. I wish I could say that this meant I read more and better, but instead both my memory and my records show that it was a pretty uneven reading year, with a lot of slumps. The summer especially, which used to be a rich reading season for me, had almost no highlights: the best books I read in 2025 were at the very beginning and the very end of the year. Connie Willis’s

Connie Willis’s  The best non-fiction I read was Claire Cameron’s memoir

The best non-fiction I read was Claire Cameron’s memoir  A near miss:

A near miss:  And on that faintly elegiac note I will add that I reread

And on that faintly elegiac note I will add that I reread  I have still not deciphered the mystery of the hare. She remains the elusive, indefinable core that explains, perhaps, why we humans have projected so many of our fears and desires onto the species, investing hares with supernatural powers from the most evil to the most inviting, confirming our tendency to either worship or demonise those things we struggle to understand. The hare lends itself as a symbol of the transience of life and its fleeting glory, and our dependence on nature and our careless destruction of it. But in the hare’s—and nature’s—endless capacity for renewal, we can find hope. If it is possible, as William Blake would have it, ‘to see a world in a grain of sand’, then perhaps we can see all nature in a hare: its simplicity and intricacy, fragility and glory, transience and beauty.

I have still not deciphered the mystery of the hare. She remains the elusive, indefinable core that explains, perhaps, why we humans have projected so many of our fears and desires onto the species, investing hares with supernatural powers from the most evil to the most inviting, confirming our tendency to either worship or demonise those things we struggle to understand. The hare lends itself as a symbol of the transience of life and its fleeting glory, and our dependence on nature and our careless destruction of it. But in the hare’s—and nature’s—endless capacity for renewal, we can find hope. If it is possible, as William Blake would have it, ‘to see a world in a grain of sand’, then perhaps we can see all nature in a hare: its simplicity and intricacy, fragility and glory, transience and beauty. It is not an idyll: lovely as Dalton’s descriptions of the fields and woods are, the hare’s world is still that of nature “red in tooth and claw,” full of hazards and threats, violence and death, hawks and stoats and foxes. The worst carnage, however, is wrought not by nature but by man’s machinery. One day a pair of huge tractors harvest potatoes from the field next door. When they are finished, Dalton walks the furrows and finds them (in a scene worthy of Thomas Hardy) littered with dead or injured hares:

It is not an idyll: lovely as Dalton’s descriptions of the fields and woods are, the hare’s world is still that of nature “red in tooth and claw,” full of hazards and threats, violence and death, hawks and stoats and foxes. The worst carnage, however, is wrought not by nature but by man’s machinery. One day a pair of huge tractors harvest potatoes from the field next door. When they are finished, Dalton walks the furrows and finds them (in a scene worthy of Thomas Hardy) littered with dead or injured hares: One reason Raising Hare resonated with me is that over the past six months, since Freddie came to live with me, I have been experiencing on a small scale some of the same adjustments to my own sense of time and priorities. Living close to the hare helps Dalton better understand people’s bonds with their pets:

One reason Raising Hare resonated with me is that over the past six months, since Freddie came to live with me, I have been experiencing on a small scale some of the same adjustments to my own sense of time and priorities. Living close to the hare helps Dalton better understand people’s bonds with their pets:

There is more to life than great chess. Okay, great chess is still a part of life, and it can be a very big part, very intense, satisfying, and pleasant to dwell on in the mind’s eye: but nonetheless, life contains many things. Life itself, he thinks, every moment of life, is as precious and beautiful as any game of chess every played, if only you knew how to live.

There is more to life than great chess. Okay, great chess is still a part of life, and it can be a very big part, very intense, satisfying, and pleasant to dwell on in the mind’s eye: but nonetheless, life contains many things. Life itself, he thinks, every moment of life, is as precious and beautiful as any game of chess every played, if only you knew how to live. Like Rooney’s other novels Intermezzo takes people’s intimacies and relationships and feelings very seriously. It is a novel on a small scale, about two brothers muddling through some deeply felt but inadequately processed grief for their recently dead father while also muddling through their romantic entanglements, Ivan with an older woman, Margaret; Peter with a younger woman, Naomi, as well as his ex-fiancee Sylvia. I wasn’t always interested enough in Peter to care about his struggles, though that might have been the fault of the awkward style of his sections (Manov: “more Yoda than Joyce”—ouch!), or maybe it was due to my own greater sympathy, just instinctively, for Ivan’s story. Compared to Beautiful World, Intermezzo seemed less expansive, not in length but in reach. It didn’t convince me that the problems of these particular little people amounted to more than a hill of beans—and yet something felt true about its preoccupation with their problems, which really just reflects their own preoccupation with their own problems. We do, mostly, live like that, right? Even those of us who in some sense are committed to “the life of the mind” spend most of our time immersed in the petty and personal.

Like Rooney’s other novels Intermezzo takes people’s intimacies and relationships and feelings very seriously. It is a novel on a small scale, about two brothers muddling through some deeply felt but inadequately processed grief for their recently dead father while also muddling through their romantic entanglements, Ivan with an older woman, Margaret; Peter with a younger woman, Naomi, as well as his ex-fiancee Sylvia. I wasn’t always interested enough in Peter to care about his struggles, though that might have been the fault of the awkward style of his sections (Manov: “more Yoda than Joyce”—ouch!), or maybe it was due to my own greater sympathy, just instinctively, for Ivan’s story. Compared to Beautiful World, Intermezzo seemed less expansive, not in length but in reach. It didn’t convince me that the problems of these particular little people amounted to more than a hill of beans—and yet something felt true about its preoccupation with their problems, which really just reflects their own preoccupation with their own problems. We do, mostly, live like that, right? Even those of us who in some sense are committed to “the life of the mind” spend most of our time immersed in the petty and personal. Now that I had barely anything left, I could sit in peace on the bench and watch the stars dancing against the black firmament. I had got as far from myself as it is possible for a human being to get, and I realized that this state couldn’t last if I wanted to stay alive. I sometimes thought I would never fully understand what had come over me in the Alm. But I realized that everything I had thought and done until then, or almost everything, had been nothing but a poor imitation. I had copied the thoughts and actions of other people . . . There was nothing, after all, to distract me and occupy my mind, no books, no conversation, no music, nothing. Since my childhood I had forgotten how to see things with my own eyes, and I had forgotten that the world had once been young, untouched, and very beautiful and terrible. I couldn’t find my way back there, since I was no longer a child and no longer capable of experiencing things as a child, but loneliness led me, in moments free of memory and consciousness, to see the great brilliance of life again.

Now that I had barely anything left, I could sit in peace on the bench and watch the stars dancing against the black firmament. I had got as far from myself as it is possible for a human being to get, and I realized that this state couldn’t last if I wanted to stay alive. I sometimes thought I would never fully understand what had come over me in the Alm. But I realized that everything I had thought and done until then, or almost everything, had been nothing but a poor imitation. I had copied the thoughts and actions of other people . . . There was nothing, after all, to distract me and occupy my mind, no books, no conversation, no music, nothing. Since my childhood I had forgotten how to see things with my own eyes, and I had forgotten that the world had once been young, untouched, and very beautiful and terrible. I couldn’t find my way back there, since I was no longer a child and no longer capable of experiencing things as a child, but loneliness led me, in moments free of memory and consciousness, to see the great brilliance of life again. In her extreme solitude, with no prospect of ever reconnecting with another human being, the narrator faces the world with no insulation between herself and everything else, from the vastness of the landscape to the equal vastness of these existential questions. Sometimes, of course, she is too worn out from the digging and scything and hiking and chopping and hunting to think about them, or about much of anything, but at other times she thinks back on her life before (or is it outside?) the wall, on “the woman I once was” and on the people she once knew:

In her extreme solitude, with no prospect of ever reconnecting with another human being, the narrator faces the world with no insulation between herself and everything else, from the vastness of the landscape to the equal vastness of these existential questions. Sometimes, of course, she is too worn out from the digging and scything and hiking and chopping and hunting to think about them, or about much of anything, but at other times she thinks back on her life before (or is it outside?) the wall, on “the woman I once was” and on the people she once knew: It’s no paradise she is living in now, and all this time to think is a curse as well as a blessing, bringing bitter grief as well as epiphanies. Who even is she, anyway, with nobody else to be present for? In one particularly striking scene she sees her own reflection and wonders what her face is for now, if she even needs it any more. Her narrative, which she calls a “report,” is her one act of resistance against her own erasure: perhaps, when she is gone, it at least will persist.

It’s no paradise she is living in now, and all this time to think is a curse as well as a blessing, bringing bitter grief as well as epiphanies. Who even is she, anyway, with nobody else to be present for? In one particularly striking scene she sees her own reflection and wonders what her face is for now, if she even needs it any more. Her narrative, which she calls a “report,” is her one act of resistance against her own erasure: perhaps, when she is gone, it at least will persist. It is a wonder that a poem, let alone an unread poem, could have such a vigorous life in the culture–and its story still had decades to run before the present day. In the late twenty-first century, even as wars broke out in the Pacific (China against South Korea, Malaysia, the Philippines and others), vanished poem and vanished opportunities coalesced into a numinous passion for what could not be had, a sweet nostalgia that did not need a resolution . . . The Corona was more beautiful for not being known. Like the play of light and shadow on the walls of Plato’s cave, it presented to posterity the pure form, the ideal of all poetry.

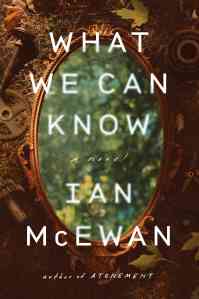

It is a wonder that a poem, let alone an unread poem, could have such a vigorous life in the culture–and its story still had decades to run before the present day. In the late twenty-first century, even as wars broke out in the Pacific (China against South Korea, Malaysia, the Philippines and others), vanished poem and vanished opportunities coalesced into a numinous passion for what could not be had, a sweet nostalgia that did not need a resolution . . . The Corona was more beautiful for not being known. Like the play of light and shadow on the walls of Plato’s cave, it presented to posterity the pure form, the ideal of all poetry. The second half of the novel offers a first-hand account of the poem’s origins, including backstory on all the figures in the poet’s life that Tom has obsessed over throughout his career. It is more conventional, high concept only in its relationship to the futuristic framing. It’s well done, though predictable and occasionally (I thought) a bit too contrived in some of its details. When I reached its rather pat ending, I found myself wondering if I had missed something that would be apparent on a re-reading of the whole novel: I think of how the early parts of Atonement, for example, vibrate with new meaning once you have read to the end, including not just the metafictional twist but also the way Briony’s fictionalization turns out to have incorporated advice you later learn she got from readers and editors. Tom’s version of the story is, I think it’s fair to say, an idealization, a kind of wishful thinking, a story that fits the evidence he has together to suit his vision of the people and events. It is inaccurate, not just because his information is copious but incomplete, but because what he wants to do (as Dorothea Brooke would put it, to reconstruct a past world, with a view to the highest purposes of truth!) is always already impossible. OK, I get it! I got that before I read the ‘real’ version—which is also, of course, inevitably partial, perhaps dubiously reliable. But do we learn something more specific about Tom’s version, are there specific things he gets wrong, or (to consider another possibility) is there evidence he mentions that undermines the version that makes up the novel’s second half? I didn’t notice any such clever moments, but there’s a lot I didn’t notice about Atonement on my first reading.

The second half of the novel offers a first-hand account of the poem’s origins, including backstory on all the figures in the poet’s life that Tom has obsessed over throughout his career. It is more conventional, high concept only in its relationship to the futuristic framing. It’s well done, though predictable and occasionally (I thought) a bit too contrived in some of its details. When I reached its rather pat ending, I found myself wondering if I had missed something that would be apparent on a re-reading of the whole novel: I think of how the early parts of Atonement, for example, vibrate with new meaning once you have read to the end, including not just the metafictional twist but also the way Briony’s fictionalization turns out to have incorporated advice you later learn she got from readers and editors. Tom’s version of the story is, I think it’s fair to say, an idealization, a kind of wishful thinking, a story that fits the evidence he has together to suit his vision of the people and events. It is inaccurate, not just because his information is copious but incomplete, but because what he wants to do (as Dorothea Brooke would put it, to reconstruct a past world, with a view to the highest purposes of truth!) is always already impossible. OK, I get it! I got that before I read the ‘real’ version—which is also, of course, inevitably partial, perhaps dubiously reliable. But do we learn something more specific about Tom’s version, are there specific things he gets wrong, or (to consider another possibility) is there evidence he mentions that undermines the version that makes up the novel’s second half? I didn’t notice any such clever moments, but there’s a lot I didn’t notice about Atonement on my first reading.