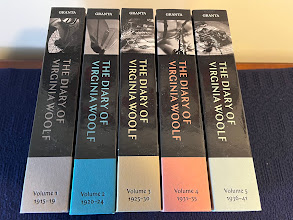

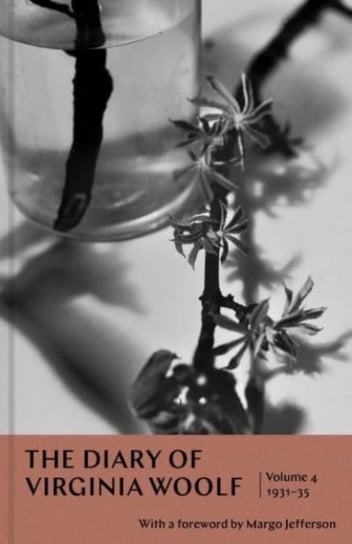

I have not stopped reading through Woolf’s diaries. I finished Volume 3 some time ago and have begin Volume 4. I have not stopped finding memorable or thought-provoking or delightful moments in them: Volume 3 is festooned with post-it flags, and Volume 4 is on a similar track.

And yet.

I have not been posting about it as much because the truth is, in between the post-it flags are often long stretches I’m not very interested in.

There, I admitted it! But I do feel sheepish about it, which is perhaps foolish. Why, after all, would I have expected to be fascinated by every page of someone’s actual diary? Nobody’s life, not even the life of a genius, is 100% fascinating; even Woolf, a genius, cannot make (and to be fair is not even trying to make) every moment fascinating.

She does a lot of socializing. People come over, she goes to their place, they hang out, they chat, they dine out, they gossip. I can’t always be bothered to read all the notes telling me who everybody is. Sometimes I even have to remind myself who “Roger” is. A lot of her reporting on this stuff is just not very interesting to me. I start to skim during accounts of conversations that seem like even in real time they were a bit tedious for her. She frets quite a bit about servants; by and large these are not her best moments.

She keeps at the diary as writing practice, as a routine, as a record, sometimes as a chore. It was never meant to be her masterpiece, or her legacy.

The best parts of Volume 3, for me, were her comments on the composition of The Waves. At the beginning of Volume 4, she is just finishing it: “Here in the few minutes that remain, I must record, heaven be praised,” she writes on February 7 1931, “the end of The Waves”:

I wrote the words O Death fifteen minutes ago, having reeled across the lasdt ten pages with some moments of such intensity and intoxication that I seemed only to stumble after my own voice . . . Anyhow it is done . . . How physical the sense of triumph & relief is! Whether good or bad, its done; & as I certainly felt at the end, not merely finished, but rounded off, completed, the thing stated–how hastily, how fragmentarily I know; but I mean that I have netted that fin in the waste of waters which appeared to me over the marshes out of my window at Rodmell when I was coming to an end of To the Lighthouse.

It is vicariously thrilling to share in that sense of “triumph & relief,” and humbling to imagine the mind and the craft and the courage it took to realize that vision in words and in such daring form. In November, when the novel has been published, the exhilaration continues:

Oh yes, between 50 & 60 I think I shall write out some very singular books, if I live. I mean I think I am about to embody, at last, the exact shapes my brain holds. What a long toil to reach this beginning–if The Waves is my first work in my own style!

If only it were all like that!

It can’t be, of course, and if it were it would be exhausting, unsustainable for her as well as for us. It’s true that there’s always the option of reading only her ‘Writer’s Diary,’ as “curated” by Leonard. But that would mean no chance of discovering the other delights and oddities and poignancies of the day to day records, which are not (and of course they are not) all dull. I loved reading about her “astonishing hat”! And many of my post-it flags bring me back to moments of personal reflection, some of them vivid and moving in the moment and more so, painfully so, knowing what we know, what she did not yet know, about the story of her life:

The thing is now [she writes in May 1930] to live with energy & mastery, desperately. To despatch each day high handedly. To make much shorter work of the day than one used. To feel each like a wave slapping up against one. So not to dawdle & dwindle, contemplating this & that. To do what ever comes along with decision; going to the Hawthornden prize giving rapidly & lightheartedly; to buy a coat; to Long Barn; to Angelica’s School; thrusting through the mornings work (Hazlitt now) then adventuring. And when one has cleared a way, then to go directly to a shop & buy a desk, a book case. No more regrets & indecisions. That is the right way to deal with life now that I am 48: & to make it more & more important and vivid as one grows old.

That seems like the right way to deal with life now that I am 58 as well.

So I will press on, allowing her to be boring sometimes and trying not to feel that my boredom is a sign of my own inadequacy! In Volume 4 she has begun work on what becomes first The Pargiters, then Three Guineas and The Years. One of my first post-its: “I’m quivering & itching to write my–whats it to be called?–‘Men are like that?'”

How I hate the word “relatable,” which is so often a shorthand for “like me and thus likeable,” which in turn is both a shallow standard for merit and a lazy way to react to a character. And yet sometimes it’s irresistible as a way to capture the surprise of finding out that someone who otherwise seems so different, elusive, iconic, really can be in some small way just like me—a writer of genius, for example, who reacts to invitations by worrying that she has nothing nice to wear and doesn’t look very good in what she does have. Yes, the period of Woolf’s diary I am reading is one of great intellectual and artistic flourishing, and this makes it all the more touching as well as oddly endearing that she frets so much about “powder & paint, shoes & stockings.” “My own lack of beauty depresses me today,” she writes on March 3, 1926;

How I hate the word “relatable,” which is so often a shorthand for “like me and thus likeable,” which in turn is both a shallow standard for merit and a lazy way to react to a character. And yet sometimes it’s irresistible as a way to capture the surprise of finding out that someone who otherwise seems so different, elusive, iconic, really can be in some small way just like me—a writer of genius, for example, who reacts to invitations by worrying that she has nothing nice to wear and doesn’t look very good in what she does have. Yes, the period of Woolf’s diary I am reading is one of great intellectual and artistic flourishing, and this makes it all the more touching as well as oddly endearing that she frets so much about “powder & paint, shoes & stockings.” “My own lack of beauty depresses me today,” she writes on March 3, 1926; No sooner is she feeling more at ease, even easy, about how she looks, then stupid Clive Bell has to go and ruin everything:

No sooner is she feeling more at ease, even easy, about how she looks, then stupid Clive Bell has to go and ruin everything:

But this slight depression—what is it? I think I could cure it by crossing the channel, & writing nothing for a week . . . But oh the delicacy & complexity of the soul—for, haven’t I begun to tap her & listen to her breathing after all? A change of house makes me oscillate for days. And thats [sic] life; thats wholesome. Never to quiver is the lot of Mr. Allinson, Mrs. Hawkesford, & Jack Squire. In two or three days, acclimatised, started, reading & writing, no more of this will exist. And if we didn’t live venturously, plucking the wild goat by the beard, & trembling over precipices, we should never be depressed, I’ve no doubt, but already should be faded, fatalistic & aged.

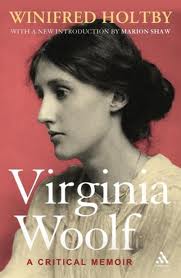

But this slight depression—what is it? I think I could cure it by crossing the channel, & writing nothing for a week . . . But oh the delicacy & complexity of the soul—for, haven’t I begun to tap her & listen to her breathing after all? A change of house makes me oscillate for days. And thats [sic] life; thats wholesome. Never to quiver is the lot of Mr. Allinson, Mrs. Hawkesford, & Jack Squire. In two or three days, acclimatised, started, reading & writing, no more of this will exist. And if we didn’t live venturously, plucking the wild goat by the beard, & trembling over precipices, we should never be depressed, I’ve no doubt, but already should be faded, fatalistic & aged. Winifred Holtby’s chapter on this period of Woolf’s life is called “The Adventure Justified”: “she was more sure now,” Holtby writes, “both of herself and of her public. She dared take greater risks with them, confident that they would not let her down.” It’s a wonderful chapter, rising almost to ecstasy about Woolf’s achievement in To the Lighthouse:

Winifred Holtby’s chapter on this period of Woolf’s life is called “The Adventure Justified”: “she was more sure now,” Holtby writes, “both of herself and of her public. She dared take greater risks with them, confident that they would not let her down.” It’s a wonderful chapter, rising almost to ecstasy about Woolf’s achievement in To the Lighthouse: It has been very quiet here lately, for reasons that may seem counterintuitive: I have had very little going on, because (long story short) the faculty at Dalhousie has been locked out by the administration since August 20, and while I am not in the union (I’m a member of the joint King’s – Dalhousie faculty) I have been instructed to do no Dal-specific work while the labour dispute continues. You’d think that this would mean I have all kinds of time to read books and write about them here, and yet what has happened instead is that the weird limbo of this situation has prolonged

It has been very quiet here lately, for reasons that may seem counterintuitive: I have had very little going on, because (long story short) the faculty at Dalhousie has been locked out by the administration since August 20, and while I am not in the union (I’m a member of the joint King’s – Dalhousie faculty) I have been instructed to do no Dal-specific work while the labour dispute continues. You’d think that this would mean I have all kinds of time to read books and write about them here, and yet what has happened instead is that the weird limbo of this situation has prolonged

I have also been continuing my read-through of Woolf’s diaries. I am into 1923 now. 1922 seemed like a slow year and then she published Jacob’s Room and read Ulysses, both of which events generated a lot of interesting material. I am fascinated by her self-doubt: we meet great writers of the past when that greatness is assured, and also when their writer’s identity is established, but Woolf is not so sure on either count, and is hypersensitive—as George Eliot was—to criticism, especially when she felt her work was misunderstood, not just unappreciated. Jacob’s Room is significant because it is the first novel that, to her, really feels like her own voice: “There’s no doubt in my mind,” she says, “that I have found out how to begin (at 40) to say something in my own voice; & that interests me so that I feel I can go ahead without praise.” I am always fascinated and inspired by accounts of artists of any kind who find their métier and know it; I still think often of

I have also been continuing my read-through of Woolf’s diaries. I am into 1923 now. 1922 seemed like a slow year and then she published Jacob’s Room and read Ulysses, both of which events generated a lot of interesting material. I am fascinated by her self-doubt: we meet great writers of the past when that greatness is assured, and also when their writer’s identity is established, but Woolf is not so sure on either count, and is hypersensitive—as George Eliot was—to criticism, especially when she felt her work was misunderstood, not just unappreciated. Jacob’s Room is significant because it is the first novel that, to her, really feels like her own voice: “There’s no doubt in my mind,” she says, “that I have found out how to begin (at 40) to say something in my own voice; & that interests me so that I feel I can go ahead without praise.” I am always fascinated and inspired by accounts of artists of any kind who find their métier and know it; I still think often of

In my previous post I wondered whether we knew what Woolf’s wishes were for her diary: whether she imagined it as something others would someday read, or thought of it as—and hoped it would remain—a private space. How might these different ideas about what she was writing, or who she was writing for, have affected what she wrote? With these questions still lingering as I read on yesterday, I reached an entry that explicitly addresses what keeping a diary meant to her and what her aspirations were for it, particularly for herself as a writer. It’s a longish passage but I’m going to copy the whole of it here, because I find every bit of it so interesting. It’s part of her entry for Sunday 20 April, 1919.

In my previous post I wondered whether we knew what Woolf’s wishes were for her diary: whether she imagined it as something others would someday read, or thought of it as—and hoped it would remain—a private space. How might these different ideas about what she was writing, or who she was writing for, have affected what she wrote? With these questions still lingering as I read on yesterday, I reached an entry that explicitly addresses what keeping a diary meant to her and what her aspirations were for it, particularly for herself as a writer. It’s a longish passage but I’m going to copy the whole of it here, because I find every bit of it so interesting. It’s part of her entry for Sunday 20 April, 1919. I love that.

I love that. At first I was thinking that not much was really happening in this section, but then it struck me that of course there is a war on, as we are reminded by several passing references to German prisoners working on the nearby farms: “To picnic near Firle,” she reports on August 11, for example, “with Bells &c. Passed German prisoners, cutting wheat with hooks.” Also during this period Leonard is called up to military service, and their efforts to have him excused on medical grounds are repeatedly mentioned. Once they are back at Richmond, they are constantly on edge about air raids: on December 6, she is “wakened by L. to a most instant sense of guns: as if one’s faculties jumped up fully dressed.” They retreat to the kitchen passage then go back to bed when the danger seems passed, only to be once again roused by “guns apparently at Kew.” The raid, the papers tell her the next day, “was the work of 25 Gothas, attacking in 5 squadrons, and 2 were brought down.”

At first I was thinking that not much was really happening in this section, but then it struck me that of course there is a war on, as we are reminded by several passing references to German prisoners working on the nearby farms: “To picnic near Firle,” she reports on August 11, for example, “with Bells &c. Passed German prisoners, cutting wheat with hooks.” Also during this period Leonard is called up to military service, and their efforts to have him excused on medical grounds are repeatedly mentioned. Once they are back at Richmond, they are constantly on edge about air raids: on December 6, she is “wakened by L. to a most instant sense of guns: as if one’s faculties jumped up fully dressed.” They retreat to the kitchen passage then go back to bed when the danger seems passed, only to be once again roused by “guns apparently at Kew.” The raid, the papers tell her the next day, “was the work of 25 Gothas, attacking in 5 squadrons, and 2 were brought down.”