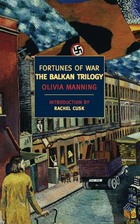

One of the many enticing volumes in the NYRB Classics series is Olivia Manning’s The Balkan Trilogy. I wish this nice edition had been available when I went on a quest for The Balkan Trilogy and its sequel, The Levant Trilogy, to read a couple of years ago; I had to settle for musty second-hand copy of the old Penguin editions. They proved well worth looking for, though, despite (or perhaps because of) not being at all what I expected. My write-up of the series follows; for further reading, the NYRB edition of The Balkan Trilogy comes with a very perceptive introduction by Rachel Cusk:

Indifference, injustice, cruelty, hatred, neglect: in The Balkan Trilogy these are the constituents both of personal memory and of social reality, of private unhappiness and of public violence. In Olivia Manning’s analogy, war is the work of unhappy children; but while Harriet embodies the darkness of this perception, she represents too the individual struggle to refute it.

After reading and then writing about this series, I went looking for critical work on Manning and found very little. Perhaps this release of The Balkan Trilogy, as well as her earlier novel School for Love, will turn more attention her way.

This two-volume set is actually a sextet of shorter novels, the first three comprising The Balkan Trilogy, the second The Levant Trilogy. According to my Penguin editions, Anthony Burgess described this series as “the finest fictional record of the war produced by a British writer.” The war in question is, of course, the second World War, but if Burgess’s remark leads you to expect a sweeping war-time saga full of action, heroism, drama and suspense, you’ll be surprised–as I was. In the first volume, set first in Romania and then in Greece, our protagonists are at the periphery of the conflict, which is spreading through Europe and gradually encroaches on their lives without ever directly reaching it, as they leave both Bucharest and then Athens on the eve of German occupation. All of the motley array of characters are versions of Rosencrantz and Guildenstern, bit players with no important part to play in the real story, except that theirs is the story, and it’s not comic–or tragic, either. (Some textual evidence that Manning herself conceived of her characters in this way comes in the Coda to The Levant Trilogy, in which she compares them to “the stray figures left on the stage at the end of a great tragedy”). The novels unfold in a strangely muted register that matches the characters’ global insignificance even as the interest, and pathos of their circumstances and their endearing and irritating individual characteristics eventually win us over to believing in and caring about them.

I was fascinated with the picture Manning offers of the British abroad in this particular historical moment; the novels are highly autobiographical, or at any rate follow closely the historical and geographical situations she and her husband experienced, and Manning was clearly an astute observer of the both the local and the expatriat cultures she participated in. She is particularly understated and yet pointed (if that’s not too paradoxical a description) about the anti-Semitism in Romania, illustrating its character and effects while keeping its worst realities just off-stage. The horrible truths are shown most explicitly through the story of the banker Drucker, whose son Sasha the Pringles eventually shelter in their flat. Imprisoned by the Romanians ostensibly for trading in currency on the black market but really, it is clear, for the crime of being a rich Jew, he is eventually released for trial, and Harriet Pringle goes on Sasha’s behalf to get a look at how he has fared:

Harriet, who had seen Drucker only once, ten months before, remembered him as a man in fresh middle age, tall, weighty, elegant, handsome, who had welcomed her with a warm gaze of admiration.

What appeared was an elderly stooping skeleton, a cripple who descended the steps by dropping the same foot each time and dragging the other after. The murmurs of ‘Drucker’ told her that, whether she could believe it or not, this was he. Then she recognised the suit of English tweed he had been wearing when he had entertained the Pringles to luncheon. The suit was scarcely a suit at all now….

From the bottom step he half-smiled, as if in apology, at his audience, then, seeing Harriet, the only woman present, he looked puzzled. He paused and one of the warders gave him a kick that sent him sprawling over the narrow pavement. As he picked himself up, there came from him a stench like the stench of a carrion bird. The warder kicked at him again and he fell forward, clutching at the van steps and murmuring “Da, da,” in zealous obedience.

Harriet’s specific emotional response is not elaborated on, and why should it be? We have, presumably, shared it, and we understand her decision, arriving home, to “deceive Sasha. He was never likely to see his father again.” She reports only “‘Your father looked very well,'” and that kind, protective lie speaks eloquently of the destructive inhumanity of the truth. Key moments of high suspense or emotion are treated in this cool, matter-of-fact way throughout, as when the Pringles arrive home to find that Sasha has been taken in a raid:

The bed-covers were on the floor, and as Harriet piled them back on to the bed, the mouth-organ fell from among them. She handed it to Guy as proof that he had been taken, and forcibly. Under the bed-covers was the forged passport, torn in half – derisively, it seemed.

Remembering her childhood pets whose deaths had broken her heart, she said: “They’ll murder him, of course.”

The next day, “Harriet [is] surprised that she felt nothing.” The risk, in both her consciousness and the narrative, seems to be that, in such circumstances, the only options are feeling nothing or being overwhelmed with feeling. Cumulatively, though, for this reader anyway, the effect of the persistent resistance to melodrama is a story nearly stripped of its human essentials and thus of a sense of what the novels stand for in the face of totalitarianism. Towards the end of their stay in Athens, for example, a major character whose quirks and (mis)fortunes we have followed since the first pages is unexpectedly and unnecessarily shot, more or less accidentally and at random. Is it because destruction and death are always at the margins of their lives, because the war has taken normalcy from them, that his companions feel more inconvenienced than anything else?

The manager agreed to let the body rest for the night in one of the hotel bathrooms. The four friends followed as it was carried away from the terrace and placed on a bathroom floor. As the door was locked upon it, the all clear sounded. The manager, offering his commiserations, shook hands all round and the English party left the hotel. Alan, hourly expecting an evacuation order, had decided to spend the night in his office. Ben Phipps, on his way to Psychico, dropped the Pringles off at the academy.

Pop psychology terms like “coping strategies” come to mind: these non-combatants are struggling for survival themselves, but their enemies are not the Nazis so much as the moral and social rootlessness they experience, with military victory, and thus the survival of their ‘home’ countries and values, uncertain, and with reminders of their own mortality and insignificance nearly constant.

In this context, Guy Pringle is a fascinating figure (though I don’t see why he’s the one Burgess highlights as “one of the major characters in modern fiction,” given the much greater priority given to the experience and perspective of his wife). Guy is a lecturer in English literature notable for his expansive energy, which in The Balkan Trilogy he invests in two major theatrical productions. The one treated in most detail is an amateur production of Shakespeare’s Troilus and Cressida, a project for which he recruits many of the other major characters–but, tellingly, not Harriet, with whom he declares he cannot work, because she will not take him or his effort seriously enough. His goals include raising the morale of the British residents and their friends in Bucharest as well as asserting the importance of British culture and history in the face of the military setbacks that have eroded the nation’s stature abroad–they are, after all, on the losing side at this point. The German Propaganda Bureau keeps a map in its window indicating German advances across France with “broad arrows.” “For Bucharest,” we are told, “the fall of France was the fall of civilization….With France lost, there would be no stay or force against savagery….the victory of Nazi Germany would be the victory of darkness.” In this context, Guy’s preoccupation with his play is suggestive of fiddling while Rome burns, and yet at the same time it seems defiant, an assertion of the value of art and beauty and imagination. Emerging from the theatre, the audience learns that Paris has fallen: “Chastened, they emerged into the summer night and met reality, avoiding each others’ eyes, guilty because they had escaped the last calamitous hours.” They have been experiencing freedom of the mind, the kind of freedom that these novels make you feel is the most to be cherished in wartime. And yet where is the heroism in going to the theatre while around you suffer millions unable to escape in the most literal way?

Ambivalence to Guy’s cultural projects, and indeed to Guy more generally, intensifies in The Levant Trilogy, written more than a decade after The Balkan Trilogy but picking up the story of most of the same characters as they move through another phase of displacement, this time in Egypt. Harriet’s relationship with Guy has always been strained by his inability to put her needs even on the same level as the demands placed on him by everyone else he knows, as well as by his own obsession with his work. Harriet’s discontent takes concrete form occasionally, as in a near-romance that evolves in Athens in the third novel of The Balkan Trilogy. In The Levant Trilogy, we see more of Harriet’s efforts to develop an independent identity in the face of Guy’s physical and emotional absence. In this series, though the war is brought much closer, through the character of Simon Boulderstone (is the redundancy of his surname significant?), with whom we travel to the front at last. Simon comes literally face to face with the horrors of the desert campaign:

Before him was a flat expanse of desert where the light was rolling out like a wave across the sand. Two tanks stood in the middle distance and imagining they had stopped for a morning brew-up, he decided to cross to them and ask if they had seen anything of the patrol or the batman’s truck. It was too far to walk so he went by car, following the track till he was level with the tanks, then walking across the mardam. A man was standing in one of the turrets, motionless, as if unaware of Simon’s approach. Simon stopped at a few yards’ distance to observe the figure, then saw it was not a man. It was a man-shaped cinder that faced him with white and perfect teeth set in a charred black skull. He could make out the eye-sockets and the triangle that had once supported a nose then, returning at a run, he swung the car round and drove back between the batteries, so stunned that for a little while his own private anxiety was forgotten.

We see, too, that the violence of war has the capacity to reach ‘civilians’ with no easing of its horrors. Very early in this volume, for instance, a child is brought in who has been killed by the explosion of a hand grenade he picked up while playing in the desert. In what may be the most surrealistically gruesome and disturbing scene I’ve ever read, his distraught parents refuse to interpret the signs that he has been fatally wounded and attempt to revive him by pouring gruel into a hole blown into his cheek: “The gruel poured out again. This happened three times before Sir Desmond gave up and, gathering the child into his arms, said, ‘He wants to sleep. I’ll take him to his room.'” His death prompts Harriet to think of “all the other boys who were dying in the desert before they had had a chance to live. And yet, though there was so much death at hand, she felt the boy’s death was a death apart.” Suffering was nearby throughout The Balkan Trilogy, but here we live in a community of the physically and spiritually wounded.

Yet even as the action and emotion of this trilogy had an intensity not often displayed in the earlier volume, it also seemed to me more directed at the unfolding of interior dramas for the characters, many of whom are struggling to define themselves against the expectations of others, or in the absence of well-defined or well-understood roles for themselves in the war-time conditions and foreign locations they are negotiating: Simon himself, for example, who has come to Egypt in part to follow in his brother’s footsteps, or Harriet, who eventually hitches a lift into Syria in an attempt to claim some meaning for herself beyond being Guy’s wife. Guy’s obtuseness about Harriet’s independent needs is highlighted more specifically here and his incessant busyness seems more irresponsible than it did in the first volume, perhaps because it’s not seen as serving any greater purpose. The one major cultural event ends…unexpectedly…without any of the triumphant possibilities of Troilus and Cressida, though perhaps it has as much symbolic significance of its own, maybe even marking a rejection of the idealism that Guy represented.

I haven’t really reached many interpretive conclusions about these books, but I have a lot of lingering questions. How far, for instance, do these books seek simply to chronicle how people lived through the exile from home and from normalcy imposed by the war, and how far do they prompt us to think about the global conflict as a reflection, an externalization, of abstract forces and values playing out on a personal scale as well? Is Manning’s understated style itself some kind of statement about the limitations of aesthetic responses to catastrophe, or about the necessity we are under of living life on our own small scale, however grand the larger narrative? Is Guy offered up as the embodiment of some essentially British quality, and if so, how far is it critiqued and how far accepted or encouraged?