I’m trying to get back in the habit of writing up most (maybe not all) of the books I read so here we go with a quickish update on two novels that I recently finished.

I’m trying to get back in the habit of writing up most (maybe not all) of the books I read so here we go with a quickish update on two novels that I recently finished.

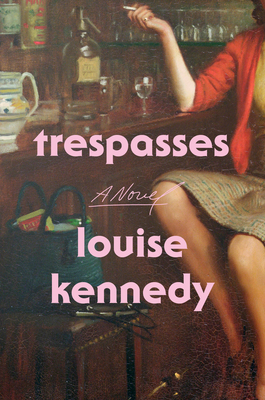

I heard a lot about Louise Kennedy’s Trespasses from other readers when it was first out, all of it good. It took me a while to get around to it, but I’m glad I kept it on my radar and grabbed it up when I came across it not long ago—a perk of being slow off the mark is that I found the nice hardcover edition on a sale table! (I often wait for the paperback, not just because hardcovers are so expensive here now but because I just prefer holding and reading paperbacks. But there’s still something satisfying about a hardcover, isn’t there?) Trespasses was definitely worth reading, though it is rough going emotionally. I thought Kennedy’s strategy of leading off chapters with quick rundowns of news items, in the same way Cushla does this with her students, was a deft way of contextualizing the novel’s plot, but also of reminding us that the “news” is not something that happens only to other people. Often I did a double-take when I realized that what seemed like just one more item was something that had happened to one of the novel’s characters. The effect was a building sense of dread, which was exacerbated by the general expectation of some kind of catastrophe, an expectation established by the setting and the specific mix of characters in the novel.

Kennedy keeps us primarily focused on the very personal story of Cushla’s life and especially her relationship with Michael Agnew, but it is impossible for this story to be only personal, for two people to just be “themselves,” exempted from politics or society. It is hard not to feel angry and frustrated on their behalf at the prejudices and persecutions that they have to navigate, but at the same time Kennedy avoids trite “can’t we all just get along?” messages, not least because both Cushla and Michael have and act on ideas about how the world around them should be—they are not bystanders or neutral observers.

In contrast, I had never heard of Jazmina Barrera’s Cross Stitch when I first spotted it in the bookstore a couple of months ago. Its title caught my eye because I do cross stitch myself, though it has been a while since I picked up any of my works in progress. (As my eyes age, it seems increasingly unlikely that I will ever finish the series of Henry VIII and his six wives that I began around 30 years ago. But never say never! I bought one of those around-the-neck magnifiers and it may make all the difference.) The novel’s blurb was appealing, but it took me a few visits to decide to actually give it a try—and unlike A Month in the Country, which I hesitated over for so much longer, Cross Stitch was not so good that I wished I had read it sooner. It wasn’t bad; there were things I really liked about it. It is a bittersweet story about friendship and the odd and sometimes sad paths it can take as people grow up and apart. The three women (initially girls) at its center, Mila, Dalia, and Citlala, are avid embroiderers, and the novel intersperses its first-person narration (by Mila, the writer of the group, of course) with reflections on needlework, including quotations from scholars and critics and other writers who have offered ideas about its role in women’s lives and in cultural history. One of these sources is Roszika Parker’s The Subversive Stitch, which was also an important source for the chapter on needlework and historiography in my academic monograph.

In contrast, I had never heard of Jazmina Barrera’s Cross Stitch when I first spotted it in the bookstore a couple of months ago. Its title caught my eye because I do cross stitch myself, though it has been a while since I picked up any of my works in progress. (As my eyes age, it seems increasingly unlikely that I will ever finish the series of Henry VIII and his six wives that I began around 30 years ago. But never say never! I bought one of those around-the-neck magnifiers and it may make all the difference.) The novel’s blurb was appealing, but it took me a few visits to decide to actually give it a try—and unlike A Month in the Country, which I hesitated over for so much longer, Cross Stitch was not so good that I wished I had read it sooner. It wasn’t bad; there were things I really liked about it. It is a bittersweet story about friendship and the odd and sometimes sad paths it can take as people grow up and apart. The three women (initially girls) at its center, Mila, Dalia, and Citlala, are avid embroiderers, and the novel intersperses its first-person narration (by Mila, the writer of the group, of course) with reflections on needlework, including quotations from scholars and critics and other writers who have offered ideas about its role in women’s lives and in cultural history. One of these sources is Roszika Parker’s The Subversive Stitch, which was also an important source for the chapter on needlework and historiography in my academic monograph.

But I couldn’t really see what the embroidery material, or the women’s stitching, meant to the story Barrera tells of their lives, even though some of the explicit comments she makes about stitching and (or vs) writing were clever or thought-provoking. “I’ve never, and will never, read one of those books on how to write fiction,” Mila remarks at one point,

but it occurs to me that a novel could be written based on the instructions in needlework manuals, taking the following statements as if they were wise, disinterested pieces of advice:

‘When embroidering the foundation, always use a sharp needle.’

‘Don’t pull the thread too tightly; if you do, the loop becomes narrow and the effect is lost.’

‘Do exactly the same but in mirror image, reducing by one line at each step.’

‘When you stop embroidering, the work should be taken from the frame to allow the cloth to breath.’

I wonder whether, if I reread Cross Stitch really attentively, I would find that she has applied these lessons to the novel she’s narrating. I don’t expect I will reread it, though: it just wasn’t engaging enough. It had very little momentum, something I should perhaps have anticipated from the way the text is broken up into smaller and larger pieces, separated (a bit too cutely?) by small images of a needle and thread.

As a coming of age novel, Cross Stitch definitely had its interest for me: Barrera is Mexican (the novel is translated by Christina MacSweeney), so it comes at those themes from its own angle, including both the girls’ experiences growing up in Mexico and their travels to London and Paris. I never know with a translated novel how much of my experience of it is actually a result of the translation; I found Cross Stitch a bit stilted or flat, but that’s something I find with a lot of English novels these days too, as cool, crisp writing is very much in vogue, so it may be as much a decision about how to present Barrera’s writing as it is a reflection of what it’s like in the original.