I thought I had done very little reading in July, and I was prepared to defend myself: “Fred! Very distracting! Too hot! Can’t concentrate!” Both of these things are true: having Fred in my life has been a significant adjustment, more than I expected, and we did have a pretty warm July. Both factors contributed to a pretty poor month for sleeping, so I was going to point to that too as a reason I read so little.

I thought I had done very little reading in July, and I was prepared to defend myself: “Fred! Very distracting! Too hot! Can’t concentrate!” Both of these things are true: having Fred in my life has been a significant adjustment, more than I expected, and we did have a pretty warm July. Both factors contributed to a pretty poor month for sleeping, so I was going to point to that too as a reason I read so little.

And yet it turns out I read 11.5 books in July, which is more than many other months. So why did it seem like such a slump? I think it’s because most of them were not very deep, or not very good—plus two of them were re-reads, which I feel is sort of cheating.

The unexpected highlight was a very last minute choice: an interesting conversation with my lovely mom about A. S. Byatt convinced me I should reread the ‘Frederica quartet,’ but I felt too lackadaisical that night to jump right in so I plucked Byatt’s The Matisse Stories off the shelf on July 30 and finished it July 31. I’ve owned it for ages (I think it was a book sale find) but hadn’t gotten around to it. It turns out to be a really fascinating trio of stories all related (surprise! 🙂 ) in some way to paintings by Matisse, though in unpredictable ways. In the first one, a middle-aged woman reaches a breaking point at the salon and ends up absolutely trashing the place: I would never do such a thing to my nice stylist or the pleasant salon she co-owns, but there was something profoundly understandable about this woman’s rage. In the second, a self-absorbed, pretentious artist endlessly catered to (if silently criticized) by his deferential wife gets an unexpected come-uppance when it turns out their cleaning lady is the one whose wild artistic creations get noticed. The third turns on an accusation against a professor by a student who is clearly unwell; there’s a lot of thought-provoking discussion in it about art and standards, but what will stay with me is a stark moment of acknowledgment between two people who, it becomes clear, have both considered ending their lives:

The unexpected highlight was a very last minute choice: an interesting conversation with my lovely mom about A. S. Byatt convinced me I should reread the ‘Frederica quartet,’ but I felt too lackadaisical that night to jump right in so I plucked Byatt’s The Matisse Stories off the shelf on July 30 and finished it July 31. I’ve owned it for ages (I think it was a book sale find) but hadn’t gotten around to it. It turns out to be a really fascinating trio of stories all related (surprise! 🙂 ) in some way to paintings by Matisse, though in unpredictable ways. In the first one, a middle-aged woman reaches a breaking point at the salon and ends up absolutely trashing the place: I would never do such a thing to my nice stylist or the pleasant salon she co-owns, but there was something profoundly understandable about this woman’s rage. In the second, a self-absorbed, pretentious artist endlessly catered to (if silently criticized) by his deferential wife gets an unexpected come-uppance when it turns out their cleaning lady is the one whose wild artistic creations get noticed. The third turns on an accusation against a professor by a student who is clearly unwell; there’s a lot of thought-provoking discussion in it about art and standards, but what will stay with me is a stark moment of acknowledgment between two people who, it becomes clear, have both considered ending their lives:

‘Of course, when one is at that point, imagining others becomes unimaginable. Everything seems clear, and simple, and single; there is only one possible thing to be done—’

Perry Diss says,

‘That is true. You look around you and everything is bleached, and clear, as you say. You are in a white box, a white room, with no doors or windows. You are looking through clear water with no movement—perhaps it is more like being inside ice, inside the white room. There is only one thing possible. It is all perfectly clear and simple and plain. As you say.’

I don’t know if they are right, but when I read this what I thought to myself was “How did Byatt know this?” It feels as if it must be true. Byatt is such a consistently smart writer; I do absolutely look forward to starting in on The Virgin in the Garden.

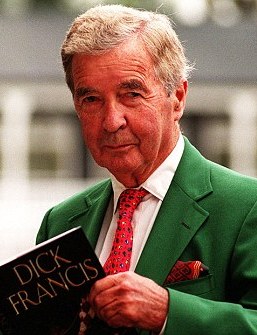

Nothing else I read made me think or feel as much as this little volume. I quite liked Ian Rankin’s Midnight and Blue; it has been especially fun watching Rankin push Rebus along through the years rather than preserving him in eternal crime-fighting youth. I also liked Kate Atkinson’s Death at the Sign of the Rook. I read Peter Hoeg’s Smilla’s Sense of Snow for my book club (I’m not considering this a re-read as it had been more than 30 years since my first go at it!). It starts out so strong! It goes so awry! It ends . . . with a parasitic worm? Really? Katerina Bivald’s The Murders in Great Diddling was mildly entertaining. Martha Wells’s All Systems Red—which I listened to as an audio book—was very entertaining and very short. Felix Francis’s The Syndicate was not very good: he took over his dad’s franchise and some of the results have been fine, but this one read like someone ticking off boxes.

Nothing else I read made me think or feel as much as this little volume. I quite liked Ian Rankin’s Midnight and Blue; it has been especially fun watching Rankin push Rebus along through the years rather than preserving him in eternal crime-fighting youth. I also liked Kate Atkinson’s Death at the Sign of the Rook. I read Peter Hoeg’s Smilla’s Sense of Snow for my book club (I’m not considering this a re-read as it had been more than 30 years since my first go at it!). It starts out so strong! It goes so awry! It ends . . . with a parasitic worm? Really? Katerina Bivald’s The Murders in Great Diddling was mildly entertaining. Martha Wells’s All Systems Red—which I listened to as an audio book—was very entertaining and very short. Felix Francis’s The Syndicate was not very good: he took over his dad’s franchise and some of the results have been fine, but this one read like someone ticking off boxes.

I reread David Nicholls’s You are Here and enjoyed it about as much as the first time. That’s probably enough times, though: I can’t see it becoming one of my go-to comfort reads. Katherine Center’s How to Walk Away and Abby Jimenez’s Life’s Too Short were pretty trauma-riddled for romances (maybe that’s not the right category for them?); Center’s The Rom-Commers was another re-read and I think I actually liked it better the second time.

The 0.5 is Ali Smith’s Gliff. I lost traction on it about half way through. Smith is a hit-or-miss author for me: I think she’s brilliant and absolutely love listening to her talk about her fiction, but the Seasonal Quartet are the only novels of hers that I have gotten along with well at all.

The 0.5 is Ali Smith’s Gliff. I lost traction on it about half way through. Smith is a hit-or-miss author for me: I think she’s brilliant and absolutely love listening to her talk about her fiction, but the Seasonal Quartet are the only novels of hers that I have gotten along with well at all.

I am not, by training or inclination, a reading snob but it is interesting to recognize that my sense that I wasn’t “really” reading much is due in part to so many of these books being non-literary (in the genre sense). If they’d been better examples of their kind, though, I don’t think I would have felt the same.

[The essay for which this reading was preparation was

[The essay for which this reading was preparation was  5. Proof (1984): In this one, Tony Beach, wine merchant, is on the site of a terrible accident and ends up drawn into its causes and facing off against some of Francis’s most cold-blooded villains (I’ll just say plaster of Paris and leave it at that). The investigation includes a lot of drinking — mostly scotch, and we get a lot of expert information about how it’s made and how to tell one kind from another. Tony is one of Francis’s best characters: a widower, he is broken with grief for his lost wife, while as the son of a military man, he is painfully conscious that he isn’t living up to his father’s standard of courage and masculinity.

5. Proof (1984): In this one, Tony Beach, wine merchant, is on the site of a terrible accident and ends up drawn into its causes and facing off against some of Francis’s most cold-blooded villains (I’ll just say plaster of Paris and leave it at that). The investigation includes a lot of drinking — mostly scotch, and we get a lot of expert information about how it’s made and how to tell one kind from another. Tony is one of Francis’s best characters: a widower, he is broken with grief for his lost wife, while as the son of a military man, he is painfully conscious that he isn’t living up to his father’s standard of courage and masculinity. 2. and 3. Whip Hand (1979) and Come to Grief (1995): There’s a good case to be made for ranking at least one of these as Number 1. The protagonist in both is former-jockey-turned-private-eye Sid Halley, who actually appears in four books altogether. The first, Odds Against, is also quite good, but the last one, Under Orders (2006) is one of only two Dick Francis novels that I consider real duds (the other is Blood Sport). Sid is Francis’s best-developed and most complex and interesting character, the array of secondary characters is robust and, again, interesting, and the plots are among Francis’s best. The title Whip Hand alludes to Sid’s greatest weakness: before Odds Against begins, his left hand was badly damaged in a racing accident, forcing his retirement; I won’t give away exactly what happens, but in the next two books he has a prosthetic left hand and greatly fears damaging or losing his right one. His blend of persistent, almost obstinate courage with soul-crushing weakness takes the typical qualities of the Dick Francis hero — always very human, never a superhero — to an extreme.

2. and 3. Whip Hand (1979) and Come to Grief (1995): There’s a good case to be made for ranking at least one of these as Number 1. The protagonist in both is former-jockey-turned-private-eye Sid Halley, who actually appears in four books altogether. The first, Odds Against, is also quite good, but the last one, Under Orders (2006) is one of only two Dick Francis novels that I consider real duds (the other is Blood Sport). Sid is Francis’s best-developed and most complex and interesting character, the array of secondary characters is robust and, again, interesting, and the plots are among Francis’s best. The title Whip Hand alludes to Sid’s greatest weakness: before Odds Against begins, his left hand was badly damaged in a racing accident, forcing his retirement; I won’t give away exactly what happens, but in the next two books he has a prosthetic left hand and greatly fears damaging or losing his right one. His blend of persistent, almost obstinate courage with soul-crushing weakness takes the typical qualities of the Dick Francis hero — always very human, never a superhero — to an extreme. So there they are: my top ten! No doubt this list reflects my taste as much as any objective standard of quality. Also, surprisingly many others stood up very well to rereading, including sentimental favorite The Edge (which takes place on a ‘mystery’ train across Canada), Decider (I especially enjoy the insights into architecture and building), Twice Shy (which has not one but two protagonists for our crime fighting pleasure), Shattered (with lots of fascinating insight into glass-blowing) and Hot Money (which is the closest of them all to a ratiocinative mystery).

So there they are: my top ten! No doubt this list reflects my taste as much as any objective standard of quality. Also, surprisingly many others stood up very well to rereading, including sentimental favorite The Edge (which takes place on a ‘mystery’ train across Canada), Decider (I especially enjoy the insights into architecture and building), Twice Shy (which has not one but two protagonists for our crime fighting pleasure), Shattered (with lots of fascinating insight into glass-blowing) and Hot Money (which is the closest of them all to a ratiocinative mystery).