I have still not deciphered the mystery of the hare. She remains the elusive, indefinable core that explains, perhaps, why we humans have projected so many of our fears and desires onto the species, investing hares with supernatural powers from the most evil to the most inviting, confirming our tendency to either worship or demonise those things we struggle to understand. The hare lends itself as a symbol of the transience of life and its fleeting glory, and our dependence on nature and our careless destruction of it. But in the hare’s—and nature’s—endless capacity for renewal, we can find hope. If it is possible, as William Blake would have it, ‘to see a world in a grain of sand’, then perhaps we can see all nature in a hare: its simplicity and intricacy, fragility and glory, transience and beauty.

Probably the most important parts of Raising Hare, Chloe Dalton’s memoir of how she took in an abandoned leveret and, in helping it survive, found her own way to a new relationship with nature, time, and life itself, are the ones in which she turns from her immediate experience and its personal resonance to larger issues of environmentalism and conservation. “From hunting to farming and the destruction of habitats,” she observes,

we have done so much harm to hares over the centuries. For sport—in other words, for idle amusement—and in our drive for economic efficiency, putting more pressure on the land than it and its wild inhabitants can bear. The turn of the seasons and our capacity for adaptation means there is always hope that we can do things differently. But in this, as in so many areas, our practices and our methods incline towards depletion: reducing the dwindling stock of nature that remains to us, today’s needs always outweighing our aspirations for tomorrow.

Raising Hare arrives rather than begins here, though, and so rather than feeling hectoring it feels urgent: Dalton spends most of the book sharing the gradual process of her getting to know the little leveret, eventually an adult hare who gives birth to her own babies, and so we are drawn in until we are as invested in its flourishing, as interested in its mysteries, and as fearful of its possible fate as she is.

Dalton is aware from the beginning that her involvement is problematic: hares are not domesticated, and even with the best intentions, interfering with wild animals can make things worse rather than better. Still, she is unable to leave the leveret where she finds it, alone, freezing, on a track where it is vulnerable to both natural predators and vehicles. Throughout her time caring for it and then living alongside it, she does her best to let it still be wild—refusing to treat it as a pet or even to name it. She does not attempt to train it; in fact, it seems fair to say that it is the hare that trains her, over time reshaping Dalton’s habits, attitudes, and expectations. “I felt a new spirit of attentiveness to nature,” she says,

no less wonderful for being entirely unoriginal, for as old as it is as a human experience, it was new to me. For many years, the seasons had largely passed me by, my perceptions of the steady cycle of nature disrupted by travel and urban life. I had observed nature in broad brushstrokes, in primary colours, at a surface level. I had been most interested in whether it was dry enough to walk, or warm enough to eat outside with friends. I could identify only a handful of birds and trees by name. I hadn’t observed the buds unfurling, the seasonal passage of birds, the unshakeable rituals and rhythms of life in a single field or wood.

A busy professional addicted “to the adrenaline rush of responding to events and crises,” Dalton has already had her usual life disrupted by the pandemic, which has “pinned” her in the countryside, her work life shifted (as for so many of us) to hours spent at her computer. The presence of the hare brings a new element of calm into her life:

I couldn’t help but compare its serenity and steadiness to the sense of frenetic activity that had pervaded my life for years, marked by constant vigilance, unpredictability and stress.

Observing the hare’s very different existence leads her to rethink her longstanding priorities, to wonder “what else I might enjoy that I’d never considered” rather than to assume that what she wanted was “for life to go back to normal.”

It is not an idyll: lovely as Dalton’s descriptions of the fields and woods are, the hare’s world is still that of nature “red in tooth and claw,” full of hazards and threats, violence and death, hawks and stoats and foxes. The worst carnage, however, is wrought not by nature but by man’s machinery. One day a pair of huge tractors harvest potatoes from the field next door. When they are finished, Dalton walks the furrows and finds them (in a scene worthy of Thomas Hardy) littered with dead or injured hares:

It is not an idyll: lovely as Dalton’s descriptions of the fields and woods are, the hare’s world is still that of nature “red in tooth and claw,” full of hazards and threats, violence and death, hawks and stoats and foxes. The worst carnage, however, is wrought not by nature but by man’s machinery. One day a pair of huge tractors harvest potatoes from the field next door. When they are finished, Dalton walks the furrows and finds them (in a scene worthy of Thomas Hardy) littered with dead or injured hares:

I stood at the edge of the fourteen-acre field and wondered with a sinking heart how many other leverets, or indeed ground-nesting birds, had been crushed beneath those implacable wheels and now lay within the ridges or lost to sight against the rutted brown earth. It was just another day just another harvest, a scene replicated up and down the land and across the world.

By this point in the book, she has earned our companionship in her anxiety for the one particular hare she knows, which serves in turn to draw us in to her horror at the scale of destruction. Noting that the whole process was designed for one particular kind of efficiency, she asks why we cannot put our ingenuity to work to reduce the harm done:

If it is possible to create robots and drones to reap our fields for us, could we not use technology to detected the presence of leverets, and fawns, and nesting birds, and could reasonable efforts not be made to relocate them, rather than simply leaving them to be crushed beneath our machines?

I think a lot of us are asking, with growing anger as well as despair, similar questions about many of the technologies that are doing so much harm to our natural world, often without offering a compensating good anywhere near as defensible as a more abundant and affordable food supply.

Most of Raising Hare is in a different register, though, so it never feels either didactic or despairing. Dalton learns about and from the hare by observing it and sharing space with it, and eventually with some of its offspring. She writes with care and tenderness about what she sees. The animals come and go from her house (she eventually gets a ‘hare door’ built to be sure they are never confined, even when she’s not there to open or close the entrances); she comes to see the boundary between her life and theirs as similarly artificial and porous. She has to accept that it is not her place to protect them, even if she knew how; the death of one of the hare’s babies from no evident cause is a reminder of the limits of her control as well as her knowledge. It is sad, but it is also part of what it means for an animal to be wild. “My lasting memory of the little leveret,” she says, “is of a small, graceful figure, staring at the setting sun.”

One reason Raising Hare resonated with me is that over the past six months, since Freddie came to live with me, I have been experiencing on a small scale some of the same adjustments to my own sense of time and priorities. Living close to the hare helps Dalton better understand people’s bonds with their pets:

One reason Raising Hare resonated with me is that over the past six months, since Freddie came to live with me, I have been experiencing on a small scale some of the same adjustments to my own sense of time and priorities. Living close to the hare helps Dalton better understand people’s bonds with their pets:

I had come to appreciate that affection for an animal is of a different kind entirely [than for people]: untinged by the regret, complexities, and compromises of human relationships. It has an innocence and purity all its own. In the absence of verbal communication, we extend ourselves to comprehend and meet their needs and, in return, derive companionship and interest from their presence, while also steeling ourselves for inevitable pain, since their lives are for the most part much shorter than ours.

I spend a lot of time playing with Fred, and there is something so refreshingly simple about it: it’s not just that her antics often make me laugh, but that what she wants is just to play, and taking a break from my own work or chores to play with her forces me—or, to put it differently, gives me a chance—to put aside the “regrets, complexities, and compromises” and stresses and confusions and griefs that so often preoccupy me and just to be for a while. Sometimes it feels at first like an interruption, like something that takes patience, but the satisfaction of seeing her stalking and pouncing on her favourite dangly fish toy or rocketing through her tunnel always brings me around. And when she’s not playing, she’s napping, as often as possible on my lap; much like Dalton feeling inspired by the hare’s tranquility, I am calmed and soothed by Fred’s warmth and purrs. Because of her, I get up earlier now than I used to—but this means I can ease into the rest of my day, which I have come to love. I’m also very aware that while I decided to adopt her for my own reasons, now that she’s here, she has her reasons too, and she both needs and deserves my care and respect. That’s not quite the scale of revelation that comes to Dalton by way of the hare, but I think it’s related, part of the same recognition that we are, all of us, nature.

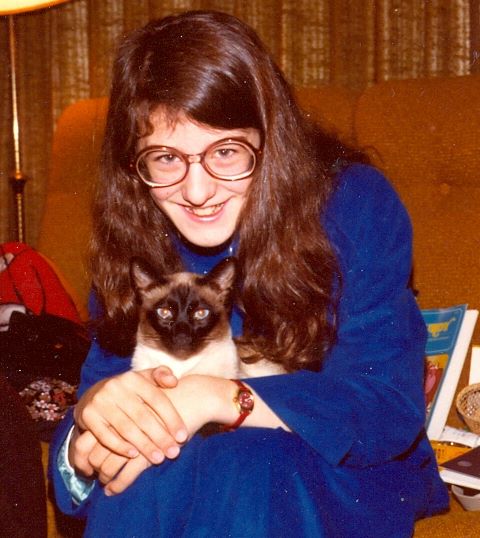

I had barely recovered from my jet lag after my recent trip to Vancouver when I got caught up in another big distraction: I have adopted a cat! Her name is Fred, short for Winifred (she happily acknowledges either

I had barely recovered from my jet lag after my recent trip to Vancouver when I got caught up in another big distraction: I have adopted a cat! Her name is Fred, short for Winifred (she happily acknowledges either  I had thought for a long time about getting a cat. I had one growing up, an elegant Siamese named Bothwell—I was in a big Mary, Queen of Scots phase when he joined the household. (Maybe Fred should consider herself lucky?) He was a great companion: loyal, eccentric, and independent, so basically a lot like me. During my marriage having a cat wasn’t an option, as my ex-husband is allergic; so too is my daughter, but only to some cats, and she encouraged me to take a chance. (So far, so good: she has visited Fred a few times and even held her, without any noticeable reaction.) I am extremely good at overthinking things, and I also don’t much like making decisions when I can’t clearly foresee the outcome, which is obviously the case when taking on a pet that is going to have her own personality and needs. I just could not get the pro / con list to be decisive either way! Then while I was away I missed out on an opportunity to adopt what sounded like the perfect cat for me, a ragdoll in sudden need of re-homing. My disappointment at not getting her clarified that I did want a cat in my life, and after an unsuccessful visit to a local shelter where the cat I went to meet first threw up at my feet then hid so I really could not get to know him, I got lucky with some help from Cat Rescue Maritimes . . . and here I am, and here we are.

I had thought for a long time about getting a cat. I had one growing up, an elegant Siamese named Bothwell—I was in a big Mary, Queen of Scots phase when he joined the household. (Maybe Fred should consider herself lucky?) He was a great companion: loyal, eccentric, and independent, so basically a lot like me. During my marriage having a cat wasn’t an option, as my ex-husband is allergic; so too is my daughter, but only to some cats, and she encouraged me to take a chance. (So far, so good: she has visited Fred a few times and even held her, without any noticeable reaction.) I am extremely good at overthinking things, and I also don’t much like making decisions when I can’t clearly foresee the outcome, which is obviously the case when taking on a pet that is going to have her own personality and needs. I just could not get the pro / con list to be decisive either way! Then while I was away I missed out on an opportunity to adopt what sounded like the perfect cat for me, a ragdoll in sudden need of re-homing. My disappointment at not getting her clarified that I did want a cat in my life, and after an unsuccessful visit to a local shelter where the cat I went to meet first threw up at my feet then hid so I really could not get to know him, I got lucky with some help from Cat Rescue Maritimes . . . and here I am, and here we are. I admit I do feel somewhat overwhelmed at the moment, both at the change to my routines and by my new responsibilities. Also, pet stores have a bewildering array of options now, and the online cat-care debates are already making me crazy. The sleep deprivation definitely adds to this! (Don’t worry: I have set up an appointment with a vet and will try to follow only evidence-based advice rather than random Redditors’.) But Fred is a sweet and incredibly affectionate and trusting little cat. I was cautioned that she would probably just hide somewhere for the first few days, but she immediately explored all the available space, spent a lot of time watching out the windows, then settled on her favorite places to nap. She loves to be held and stroked and purrs like mad when you scritch her head and around her ears—just what Bothwell liked best too. I’m hopeful that we will get better at our nighttime routines. I mean, if she can sleep in this position, surely she can also figure out how to sleep more or less when I do, right? RIGHT?! 🙂

I admit I do feel somewhat overwhelmed at the moment, both at the change to my routines and by my new responsibilities. Also, pet stores have a bewildering array of options now, and the online cat-care debates are already making me crazy. The sleep deprivation definitely adds to this! (Don’t worry: I have set up an appointment with a vet and will try to follow only evidence-based advice rather than random Redditors’.) But Fred is a sweet and incredibly affectionate and trusting little cat. I was cautioned that she would probably just hide somewhere for the first few days, but she immediately explored all the available space, spent a lot of time watching out the windows, then settled on her favorite places to nap. She loves to be held and stroked and purrs like mad when you scritch her head and around her ears—just what Bothwell liked best too. I’m hopeful that we will get better at our nighttime routines. I mean, if she can sleep in this position, surely she can also figure out how to sleep more or less when I do, right? RIGHT?! 🙂

But it turned out that although I am the only person in my book club who doesn’t own (and love) dogs, most of the others also didn’t like the book much. One was offended by it because she loves dogs and thought the book showed Alexis doesn’t actually like them: his version of them is negatively selective, uncharitable, she proposed. The nobility of the dog who waits years for his owner to come back struck a chord with some of the others (though why this dog, in spite of his grasp of human language and motives, never figures out that she has died did bother us). We all agreed with the one who cried that the last dog’s death was very pathetic — but she recently lost her own dog, so she thought she might have also been emotionally vulnerable. I was the only one who had gotten both distracted and annoyed by the weirdly specific allusions to Victorian novels (if you were going to train your preternaturally talented dog to recite just one 19th-century novel, would you choose Vanity Fair? and what is it exactly that makes Mansfield Park the pooch’s preferred Austen?). In general, the complaint was simply that it wasn’t very engaging, though as is often the case, as we talked we found it getting more interesting, at least theoretically: why does the acquisition of language so immediately cause such a deep rift? what is it about poets that makes them both outcasts and – or so Alexis proposes – the only ones likely to find happiness? We had a little fun going through the poems, too, looking for the hidden dog names that we’d missed the first time.

But it turned out that although I am the only person in my book club who doesn’t own (and love) dogs, most of the others also didn’t like the book much. One was offended by it because she loves dogs and thought the book showed Alexis doesn’t actually like them: his version of them is negatively selective, uncharitable, she proposed. The nobility of the dog who waits years for his owner to come back struck a chord with some of the others (though why this dog, in spite of his grasp of human language and motives, never figures out that she has died did bother us). We all agreed with the one who cried that the last dog’s death was very pathetic — but she recently lost her own dog, so she thought she might have also been emotionally vulnerable. I was the only one who had gotten both distracted and annoyed by the weirdly specific allusions to Victorian novels (if you were going to train your preternaturally talented dog to recite just one 19th-century novel, would you choose Vanity Fair? and what is it exactly that makes Mansfield Park the pooch’s preferred Austen?). In general, the complaint was simply that it wasn’t very engaging, though as is often the case, as we talked we found it getting more interesting, at least theoretically: why does the acquisition of language so immediately cause such a deep rift? what is it about poets that makes them both outcasts and – or so Alexis proposes – the only ones likely to find happiness? We had a little fun going through the poems, too, looking for the hidden dog names that we’d missed the first time.