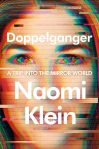

I read 16 books in August. Two were audiobooks, which is new for me: Naomi Klein’s Doppelganger (which I highly recommend) and Agatha Christie’s And Then There Were None (which was narrated wonderfully by Dan Stevens and proved an excellent choice for me to listen to, just brisk and suspenseful enough to keep my attention on walks or while crafting). Two were for reviews for Quill & Quire: Ayelet Tsabari’s Songs for the Brokenhearted (my review is submitted and will be online pretty soon, I expect) and Jenny Haysom’s Keep (this review is in progress). One was Oliver Burkeman’s The Antidote: Happiness for People Who Can’t Stand Positive Thinking (it me): I wasn’t sure I should count this, as to be honest I started skimming after a while, which is not to say it had nothing to offer me, especially its explanation of why positive thinking approaches to some kinds of mental health struggles can be not just annoying but genuinely counter-productive.

I read 16 books in August. Two were audiobooks, which is new for me: Naomi Klein’s Doppelganger (which I highly recommend) and Agatha Christie’s And Then There Were None (which was narrated wonderfully by Dan Stevens and proved an excellent choice for me to listen to, just brisk and suspenseful enough to keep my attention on walks or while crafting). Two were for reviews for Quill & Quire: Ayelet Tsabari’s Songs for the Brokenhearted (my review is submitted and will be online pretty soon, I expect) and Jenny Haysom’s Keep (this review is in progress). One was Oliver Burkeman’s The Antidote: Happiness for People Who Can’t Stand Positive Thinking (it me): I wasn’t sure I should count this, as to be honest I started skimming after a while, which is not to say it had nothing to offer me, especially its explanation of why positive thinking approaches to some kinds of mental health struggles can be not just annoying but genuinely counter-productive.

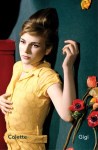

My book club decided to get in one more meeting this summer as a follow-up to our July discussion of Guy de Maupassant’s Bel-Ami. Keeping with our current French theme, we chose Gigi, which I think for all of us was our first experience of Colette. Although it’s a slight little book, it gave us plenty to talk about, from how we felt about the difference in age and maturity and agency between Gigi and her eventual fiancé to how much it is a romantic fantasy and how much a critique of the terms of that fantasy. Gigi takes a stand against her own commodification—but then she acquiesces to its terms just before she “wins” the real prize of a proposal. Does she really love Gaston? Does he really love her, or is he just getting her by whatever means he can? We were intrigued that Colette wrote the novel during the Nazi occupation of France, which perhaps gives some poignancy to its nostalgic evocation of the Belle Époque.

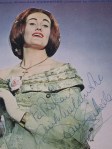

My book club decided to get in one more meeting this summer as a follow-up to our July discussion of Guy de Maupassant’s Bel-Ami. Keeping with our current French theme, we chose Gigi, which I think for all of us was our first experience of Colette. Although it’s a slight little book, it gave us plenty to talk about, from how we felt about the difference in age and maturity and agency between Gigi and her eventual fiancé to how much it is a romantic fantasy and how much a critique of the terms of that fantasy. Gigi takes a stand against her own commodification—but then she acquiesces to its terms just before she “wins” the real prize of a proposal. Does she really love Gaston? Does he really love her, or is he just getting her by whatever means he can? We were intrigued that Colette wrote the novel during the Nazi occupation of France, which perhaps gives some poignancy to its nostalgic evocation of the Belle Époque. We considered moving on to Lolita, but instead decided to stay in the French demimonde and read Dumas’ La Dame aux Camélias (in translation), which I am keen about as it is of course the origin of La Traviata, which has been my favorite opera since my parents gave me an LP of highlights from it (the Sutherland / Bergonzi recording) for my 5th birthday. Joan Sutherland signed the record cover for me when I met her backstage at the Vancouver Opera in 1977.

We considered moving on to Lolita, but instead decided to stay in the French demimonde and read Dumas’ La Dame aux Camélias (in translation), which I am keen about as it is of course the origin of La Traviata, which has been my favorite opera since my parents gave me an LP of highlights from it (the Sutherland / Bergonzi recording) for my 5th birthday. Joan Sutherland signed the record cover for me when I met her backstage at the Vancouver Opera in 1977.

I did some lighter reading that I mostly enjoyed, including two novels by Katherine Center, who I somehow had never heard of before I read Miss Bates’s review of The Rom-Commers. As often happens, after that I seemed to see her titles everywhere! I had to put a hold on the new one and my turn is still a long way away, but I was able to get What You Wish For and Happiness for Beginners from the library. I had actually watched some of the Netflix adaptation of Happiness for Beginners before, not knowing it was based on a novel, but I didn’t finish it, as I was finding it laborious and un-charming. I really liked the novel, though, more than What You Wish For, which I already forget almost entirely! Another light(er) read was David Nicholls’ Sweet Sorrow, which was a bit YA-ish for me but still pretty good. My favorite of his remains Us.

August was Women In Translation month. I didn’t go all in on this, but I did bookend the month with translated works, starting it with Maylis de Kerangal’s Painting Time and ending it with Yoko Ogawa’s The Memory Police. Neither of them thrilled me, though both definitely kept me interested. Parts of Ogawa’s novel were also really haunting, though by the end it felt too much as if she was just pushing on to get finished with the concept she had for the novel. I sometimes feel the same about the enthusiasm for reading “books in translation” as I do about the enthusiasm for “lost gems”: both are not really coherent categories, and also just because a title has reached us from the other side of the world or from across the years doesn’t exactly guarantee its merits. (As I have said elsewhere, I wonder why middling books from 60 or 70 years ago seem so much more alluring than similarly middling titles from today.) On the other hand, there is a lot more advance curation of what’s available of both of these kinds of novels and it is certainly reasonable to expect that works that do get translated into English are above average and so worth trying. And of course it is intellectually beneficial not to be too provincial in one’s reading, for sure!

August was Women In Translation month. I didn’t go all in on this, but I did bookend the month with translated works, starting it with Maylis de Kerangal’s Painting Time and ending it with Yoko Ogawa’s The Memory Police. Neither of them thrilled me, though both definitely kept me interested. Parts of Ogawa’s novel were also really haunting, though by the end it felt too much as if she was just pushing on to get finished with the concept she had for the novel. I sometimes feel the same about the enthusiasm for reading “books in translation” as I do about the enthusiasm for “lost gems”: both are not really coherent categories, and also just because a title has reached us from the other side of the world or from across the years doesn’t exactly guarantee its merits. (As I have said elsewhere, I wonder why middling books from 60 or 70 years ago seem so much more alluring than similarly middling titles from today.) On the other hand, there is a lot more advance curation of what’s available of both of these kinds of novels and it is certainly reasonable to expect that works that do get translated into English are above average and so worth trying. And of course it is intellectually beneficial not to be too provincial in one’s reading, for sure!

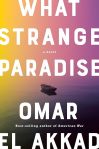

I had high expectations for both Anne Enright’s The Wren, The Wren and Selby Wynn Schwartz’s After Sappho, but neither of them excited me very much. On the other hand, I expected to find Omar El Akkad’s What Strange Paradise overhyped, but it was a highlight of my reading month—gripping, morally urgent, beautifully told. I also was very impressed with Ann Schlee’s Rhine Journey, which I was moved to read after hearing a convincing discussion of its merits on Backlisted.

Finally, I am so glad Shawn (of Shawn Breathes Books) recommended Sara Henshaw’s The Bookshop that Floated Away: it was a delight. It was more acerbic than I expected, but that was actually fine with me, as sometimes I get irritable with books that feel too obviously designed to appeal precisely to book lovers and those who (sigh) occasionally and delusionally imagine that owning a bookstore would be a lovely retirement option. (There’s this vacant house / storefront on Spring Garden Road that desperately needs salvaging and would make such a charming site . . . but even if the whole plan weren’t unsound, that property also has “money trap” written all over it.)

All in all, then, a good reading month, with lots of variety, some hits, and some misses, though even the misses were well worth reading. With classes about to start, I don’t expect to get through quite so many unassigned books in September—but having said that, I’ve been setting some goals for myself and one of them is to read more and spend less time watching TV and doomscrolling on social media. Sometimes I need these distractions: they have a useful anesthetic effect when I just can’t keep it all up (and, as I remind myself, there are worse ways to get numb when you need to). But they don’t do much for positive energy—though aspects of social media, such as book talk and podcasts, definitely do! Anyway, writing these down as intentions (and making those intentions public like this) may help me make better choices in the moment.

All in all, then, a good reading month, with lots of variety, some hits, and some misses, though even the misses were well worth reading. With classes about to start, I don’t expect to get through quite so many unassigned books in September—but having said that, I’ve been setting some goals for myself and one of them is to read more and spend less time watching TV and doomscrolling on social media. Sometimes I need these distractions: they have a useful anesthetic effect when I just can’t keep it all up (and, as I remind myself, there are worse ways to get numb when you need to). But they don’t do much for positive energy—though aspects of social media, such as book talk and podcasts, definitely do! Anyway, writing these down as intentions (and making those intentions public like this) may help me make better choices in the moment.

Another goal for the fall is to blog more, including continuing my longstanding series of posts about my teaching. I’ve been thinking a lot about what I want from the last phase of my career: I reach retirement age in 8 years, which, depending on the day, seems either very close or very far away. I don’t necessarily have to stop then—or, for that matter, to keep going until then! Things have been so turbulent in my life in recent years that I haven’t really been able to focus on this particular issue, but I do know that I don’t want to just drift towards retirement. Something ere the end, some work of noble note, may yet be done! One small gesture in this direction (though I would not say it looks like noble work at this point) is that I have volunteered for our departmental speaker series, where I will present whatever it is exactly that I’ve been doing about Woolf’s The Years. The paper’s working title is “Feeble Twaddle,” which is one way Woolf herself described the novel while she was working on it but which also often seems a fair description of the shitty rough draft I have so far produced. Being on the speakers schedule will, I hope, motivate me to wrestle it all into better shape. I think the last formal talk I gave to my department was an attempt (along these lines) to convince my colleagues about the potential merits of academic blogging—another lifetime, that seems like. That ship has probably sailed, although it has been interesting to watch my institution embrace a carefully vetted and marketed version of blogging under the rubric “Open Think.” You have to apply to participate! (Ahem, you could also just get your own free WordPress site and have at.) I guess it was the DIY version they didn’t like, maybe because they couldn’t control it, or take credit for it.

Another goal for the fall is to blog more, including continuing my longstanding series of posts about my teaching. I’ve been thinking a lot about what I want from the last phase of my career: I reach retirement age in 8 years, which, depending on the day, seems either very close or very far away. I don’t necessarily have to stop then—or, for that matter, to keep going until then! Things have been so turbulent in my life in recent years that I haven’t really been able to focus on this particular issue, but I do know that I don’t want to just drift towards retirement. Something ere the end, some work of noble note, may yet be done! One small gesture in this direction (though I would not say it looks like noble work at this point) is that I have volunteered for our departmental speaker series, where I will present whatever it is exactly that I’ve been doing about Woolf’s The Years. The paper’s working title is “Feeble Twaddle,” which is one way Woolf herself described the novel while she was working on it but which also often seems a fair description of the shitty rough draft I have so far produced. Being on the speakers schedule will, I hope, motivate me to wrestle it all into better shape. I think the last formal talk I gave to my department was an attempt (along these lines) to convince my colleagues about the potential merits of academic blogging—another lifetime, that seems like. That ship has probably sailed, although it has been interesting to watch my institution embrace a carefully vetted and marketed version of blogging under the rubric “Open Think.” You have to apply to participate! (Ahem, you could also just get your own free WordPress site and have at.) I guess it was the DIY version they didn’t like, maybe because they couldn’t control it, or take credit for it.

“Start where you are and see where it takes you” is

“Start where you are and see where it takes you” is  There’s so much emptiness in my life now. It’s not just Owen’s death, although every day I confront the ongoing ache and mystery of his absence. Some of it is the ongoing isolation of our COVID-cautious lifestyle: especially as most of the rest of the world seems to be moving on, it feels worse than it did when we were all in it together. Being back on campus and teaching in person helps with that, but it’s not the same as it was: I’m in my office a lot, but mostly with the door closed, because masks are required in classrooms but not hallways and I like to take my own mask off while I work. It’s winter, so the outdoor visits that sustained me through summer and fall are less appealing, as are my long solo walks in the park, when I was alone but, somehow, never lonely. (I often think of Marianne Moore’s line “the cure for loneliness is solitude.”) I could be busier at / with work than I am. I will be, soon, as assignments start coming in, but even so I don’t expect to be even as busy with teaching as I was last term, just because of the nature of my classes this term, the easy familiarity of one and the high degree of automation in the other. There is other work I could be doing, even a writing commitment I should be doing. I can’t seem to summon up much urgency or energy for it, though, or for the book idea I still sort of believe is worth pursuing. I’m not even reading much. I can’t seem to concentrate on most books I try; I don’t seem to like many of them, and it bothers me, worrying that it’s me, not them, that’s the problem.

There’s so much emptiness in my life now. It’s not just Owen’s death, although every day I confront the ongoing ache and mystery of his absence. Some of it is the ongoing isolation of our COVID-cautious lifestyle: especially as most of the rest of the world seems to be moving on, it feels worse than it did when we were all in it together. Being back on campus and teaching in person helps with that, but it’s not the same as it was: I’m in my office a lot, but mostly with the door closed, because masks are required in classrooms but not hallways and I like to take my own mask off while I work. It’s winter, so the outdoor visits that sustained me through summer and fall are less appealing, as are my long solo walks in the park, when I was alone but, somehow, never lonely. (I often think of Marianne Moore’s line “the cure for loneliness is solitude.”) I could be busier at / with work than I am. I will be, soon, as assignments start coming in, but even so I don’t expect to be even as busy with teaching as I was last term, just because of the nature of my classes this term, the easy familiarity of one and the high degree of automation in the other. There is other work I could be doing, even a writing commitment I should be doing. I can’t seem to summon up much urgency or energy for it, though, or for the book idea I still sort of believe is worth pursuing. I’m not even reading much. I can’t seem to concentrate on most books I try; I don’t seem to like many of them, and it bothers me, worrying that it’s me, not them, that’s the problem. Two things I did recently:

Two things I did recently:  Technically, actually, it was in someone else’s class: I was invited to come and talk about social media to our Honours Capstone Seminar, which (among other things) features a range of guest speakers talking about everything from digital humanities to graduate school to (non-academic) career paths.

Technically, actually, it was in someone else’s class: I was invited to come and talk about social media to our Honours Capstone Seminar, which (among other things) features a range of guest speakers talking about everything from digital humanities to graduate school to (non-academic) career paths. As I told the class, I really struggled with what to say. I have given quite a few talks on the subject by now, especially on blogging: these include relatively informal sessions at faculty

As I told the class, I really struggled with what to say. I have given quite a few talks on the subject by now, especially on blogging: these include relatively informal sessions at faculty  nce upon a time I might have considered these topics equally relevant for our Honours students, many of whom (in those days) were likely heading on to graduate school. A lot has changed, though, and I no longer feel comfortable actively grooming students for an academic path that (as I said to them) now seems strewn with broken glass. (There’s more about how the dismal academic job market has affected academic blogging in

nce upon a time I might have considered these topics equally relevant for our Honours students, many of whom (in those days) were likely heading on to graduate school. A lot has changed, though, and I no longer feel comfortable actively grooming students for an academic path that (as I said to them) now seems strewn with broken glass. (There’s more about how the dismal academic job market has affected academic blogging in  In my short talk, I did not go into more detail about the arguments pro and con about graduate school in the humanities (and I know there reasons, some of them pretty good ones, or at least not terrible ones, that other people still insist that encouraging students to head into Ph.D. programs is perfectly rational and ethical). I just highlighted some of the many articles they could read about it if they wanted, and urged them to talk to their professors if they were thinking about it. What I decided to use most of my own time for was making sure that they knew graduate school was not the only (and might be far from the best) way to keep talking about the literature they love in ways they find exhilarating. There are, I said, other places, other people, other opportunities, for people who love books, and I know that because of the time I spend on social media.

In my short talk, I did not go into more detail about the arguments pro and con about graduate school in the humanities (and I know there reasons, some of them pretty good ones, or at least not terrible ones, that other people still insist that encouraging students to head into Ph.D. programs is perfectly rational and ethical). I just highlighted some of the many articles they could read about it if they wanted, and urged them to talk to their professors if they were thinking about it. What I decided to use most of my own time for was making sure that they knew graduate school was not the only (and might be far from the best) way to keep talking about the literature they love in ways they find exhilarating. There are, I said, other places, other people, other opportunities, for people who love books, and I know that because of the time I spend on social media. I don’t know if they were very interested in what I had to say. If they were, they didn’t express it through a torrent of follow-up questions, that’s for sure, and I’m also pretty sure that I didn’t make a dent in anyone’s plans regarding graduate school applications. I said things I really believe in, though, which is consistent with what I would have said if I had talked about “best practices” instead, namely, be authentic. Further, and more important, as I worked up these remarks I realized that my own case for twitter and blogging is not really about their academic value anymore either. Whether the students needed or wanted to hear it or not, for me it was useful discovering that I still feel quite passionately about the positive value of reading, writing, and commenting on blog posts, and sharing ideas, tips, enthusiasms, and disagreements about reading via Twitter. Why should they care how much my life changed for the better because one day, without really knowing what I was doing or why, I pressed ‘publish’ on my first Novel Readings post? But I care, and really it has, in ways I could not possibly have predicted. So to the doubters and skeptics (if for some reason you happen to stop by), well, you do you, but I think you’re missing out. And to those of you who, like me, are out here living your best bookish life online and discovering friends and comrades along the way, cheers!

I don’t know if they were very interested in what I had to say. If they were, they didn’t express it through a torrent of follow-up questions, that’s for sure, and I’m also pretty sure that I didn’t make a dent in anyone’s plans regarding graduate school applications. I said things I really believe in, though, which is consistent with what I would have said if I had talked about “best practices” instead, namely, be authentic. Further, and more important, as I worked up these remarks I realized that my own case for twitter and blogging is not really about their academic value anymore either. Whether the students needed or wanted to hear it or not, for me it was useful discovering that I still feel quite passionately about the positive value of reading, writing, and commenting on blog posts, and sharing ideas, tips, enthusiasms, and disagreements about reading via Twitter. Why should they care how much my life changed for the better because one day, without really knowing what I was doing or why, I pressed ‘publish’ on my first Novel Readings post? But I care, and really it has, in ways I could not possibly have predicted. So to the doubters and skeptics (if for some reason you happen to stop by), well, you do you, but I think you’re missing out. And to those of you who, like me, are out here living your best bookish life online and discovering friends and comrades along the way, cheers! I am perhaps in a blogging slump, not a reading slump, though it can be hard to tell the difference. There have been a lot of comments recently about blogging as a dying form, a remnant (and how odd this characterization seems, after all the flak bloggers used to — and still do — get

I am perhaps in a blogging slump, not a reading slump, though it can be hard to tell the difference. There have been a lot of comments recently about blogging as a dying form, a remnant (and how odd this characterization seems, after all the flak bloggers used to — and still do — get  Tim is not talking about book blogging, though, and there (here) I don’t think as much has changed–or, that things have gotten so bad–though I do notice a slowing down, a fading out, not across the board but certainly among some of the folks whose blogs and comments used to be steady sources of stimulation and conversation. That seems natural, though I really miss some of them: people move on, priorities change, the intrinsic rewards of something that has never (for the kind of bloggers I follow, anyway) been tied to extrinsic rewards can fade. The times have changed, in some scary and upsetting ways, and as a result people’s anxiety is high and, amidst the hubbub, their attention is scarce and precious. Other things rightly take precedent. The ebbing of energy is contagious, too: when posting diminishes and commenting declines, and bookish people quite understandably back away from (or just get overwhelmed on) Twitter, it gets harder to imagine who you are talking to when you contemplate writing up a post yourself.

Tim is not talking about book blogging, though, and there (here) I don’t think as much has changed–or, that things have gotten so bad–though I do notice a slowing down, a fading out, not across the board but certainly among some of the folks whose blogs and comments used to be steady sources of stimulation and conversation. That seems natural, though I really miss some of them: people move on, priorities change, the intrinsic rewards of something that has never (for the kind of bloggers I follow, anyway) been tied to extrinsic rewards can fade. The times have changed, in some scary and upsetting ways, and as a result people’s anxiety is high and, amidst the hubbub, their attention is scarce and precious. Other things rightly take precedent. The ebbing of energy is contagious, too: when posting diminishes and commenting declines, and bookish people quite understandably back away from (or just get overwhelmed on) Twitter, it gets harder to imagine who you are talking to when you contemplate writing up a post yourself.

I’m not really going anywhere in particular with this: I’m just thinking out loud in public, which is what having a blog lets me do! I also trusted (because it works every time I’m in a blogging slump) that if I actually started writing something, anything, here, things would start to turn around for me, because the process itself is a tonic. “It remains important to me to think: today, I might blog,” Tim says in his post, “And to think: I have a place to do it in.” This is very much still true for me. I do a lot of other writing (well, right now it doesn’t seem like a lot, but that’s a subject for another post, especially with a sabbatical coming up) but this is the one place where I can write entirely on my own terms: no rules, no assignments, no editors, no second-guessing, no need to know what it will add up to or if I can pitch it or where I can include it on my annual report. I cherish that writing experience; when I don’t get around to doing it for a while, whether it’s because I’m too busy at work or too tired and distracted or because I think I don’t have anything to say–then I really miss it. Putting things in words is clarifying, and when I’m not under pressure, it’s also fun. Maybe blogs are now internet dinosaurs, but what matters to me (in this as in so many things) is not whether the form is trendy or innovative but what the form enables. Also, lately I’ve been feeling a bit prehistoric myself: maybe form and content are just syncing up!

I’m not really going anywhere in particular with this: I’m just thinking out loud in public, which is what having a blog lets me do! I also trusted (because it works every time I’m in a blogging slump) that if I actually started writing something, anything, here, things would start to turn around for me, because the process itself is a tonic. “It remains important to me to think: today, I might blog,” Tim says in his post, “And to think: I have a place to do it in.” This is very much still true for me. I do a lot of other writing (well, right now it doesn’t seem like a lot, but that’s a subject for another post, especially with a sabbatical coming up) but this is the one place where I can write entirely on my own terms: no rules, no assignments, no editors, no second-guessing, no need to know what it will add up to or if I can pitch it or where I can include it on my annual report. I cherish that writing experience; when I don’t get around to doing it for a while, whether it’s because I’m too busy at work or too tired and distracted or because I think I don’t have anything to say–then I really miss it. Putting things in words is clarifying, and when I’m not under pressure, it’s also fun. Maybe blogs are now internet dinosaurs, but what matters to me (in this as in so many things) is not whether the form is trendy or innovative but what the form enables. Also, lately I’ve been feeling a bit prehistoric myself: maybe form and content are just syncing up! As for the possibility of a reading slump, well, I have been reading quite a bit; I just haven’t been blogging about it, because (perhaps unsurprisingly) nothing since Lincoln in the Bardo has seemed worth much notice. I might do a ‘recent reading round-up’ type post next, just to clear the air, or I might wait and see how I do with The Fifth Season, which so far I am finding an odd balance of baffling (and thus off-putting) and gripping. Seasoned sci-fi readers assure me that if I press on, the estrangement will fade, the world-building will work its magic, and I will be on my way. We’ll see! In the meantime, at least I’ve reminded myself why I do this: because I like to.

As for the possibility of a reading slump, well, I have been reading quite a bit; I just haven’t been blogging about it, because (perhaps unsurprisingly) nothing since Lincoln in the Bardo has seemed worth much notice. I might do a ‘recent reading round-up’ type post next, just to clear the air, or I might wait and see how I do with The Fifth Season, which so far I am finding an odd balance of baffling (and thus off-putting) and gripping. Seasoned sci-fi readers assure me that if I press on, the estrangement will fade, the world-building will work its magic, and I will be on my way. We’ll see! In the meantime, at least I’ve reminded myself why I do this: because I like to.

There’s a lot else that I appreciated about Mitzi Bytes, including

There’s a lot else that I appreciated about Mitzi Bytes, including  The division (however unstable) between Sarah’s “real” life and her blogged experiences also resonated with me, but in this case because my own experience of that split in identities is the reverse of Sarah’s. Because I blog under my own name, I have mostly avoided discussion of my personal life, for instance, including writing only occasionally and very selectively about my family and almost never about my friends. I think of ‘Novel Readings’ as a personal but also a public space, not a private one. Though I have certainly addressed some fraught issues (especially around my professional life) and some emotional ones, I think (though like Sarah, I may be deluding myself!) that by and large my online persona is better (more positive, more generous, more temperate) than I sometimes am offline. It’s not that my blog doesn’t represent who am I, but like ‘Mitzi Bytes,’ ‘Novel Readings’ represents only parts of who I am — the better parts, I usually think, though over the years there have certainly been slips. Though I can see the appeal of a blog where I could really let loose, as Sarah does when writing as Mitzi (and as some anonymous academic bloggers once did – remember “BitchPhD”?), I have come to appreciate the pressure to rise to my own standards here.

The division (however unstable) between Sarah’s “real” life and her blogged experiences also resonated with me, but in this case because my own experience of that split in identities is the reverse of Sarah’s. Because I blog under my own name, I have mostly avoided discussion of my personal life, for instance, including writing only occasionally and very selectively about my family and almost never about my friends. I think of ‘Novel Readings’ as a personal but also a public space, not a private one. Though I have certainly addressed some fraught issues (especially around my professional life) and some emotional ones, I think (though like Sarah, I may be deluding myself!) that by and large my online persona is better (more positive, more generous, more temperate) than I sometimes am offline. It’s not that my blog doesn’t represent who am I, but like ‘Mitzi Bytes,’ ‘Novel Readings’ represents only parts of who I am — the better parts, I usually think, though over the years there have certainly been slips. Though I can see the appeal of a blog where I could really let loose, as Sarah does when writing as Mitzi (and as some anonymous academic bloggers once did – remember “BitchPhD”?), I have come to appreciate the pressure to rise to my own standards here.

It starts to feel as if I have written a lot of these ‘start of the term’ posts: I’ve used up every variation I can think of for titles! It’s in the nature of academic work to be cyclical, though, and on the bright side, this term I am doing one all-new course, so at least you can look forward to some novelty in my teaching posts!

It starts to feel as if I have written a lot of these ‘start of the term’ posts: I’ve used up every variation I can think of for titles! It’s in the nature of academic work to be cyclical, though, and on the bright side, this term I am doing one all-new course, so at least you can look forward to some novelty in my teaching posts! I’ve sometimes wondered if I should have had a plan, or developed one, in order to give Novel Readings a more definite identity. In the decade since I launched this blog, I’ve seen quite a lot of articles or posts giving advice on blogging, and the key to success is apparently having a mission, or filling a specific niche — along with posting on a regular (and frequent) schedule, and keeping your posts under 1000 words. (Hey, I’m 0 for 3!) I do think the hybrid identity of Novel Readings — which is not really, or at least not just, a book blog, and not really, or not altogether, an academic blog — has probably limited its appeal, because for some bookish people there’s no doubt too much academic stuff here, while for some academics, there’s too much book talk (or, too much book talk that’s not sufficiently academic).

I’ve sometimes wondered if I should have had a plan, or developed one, in order to give Novel Readings a more definite identity. In the decade since I launched this blog, I’ve seen quite a lot of articles or posts giving advice on blogging, and the key to success is apparently having a mission, or filling a specific niche — along with posting on a regular (and frequent) schedule, and keeping your posts under 1000 words. (Hey, I’m 0 for 3!) I do think the hybrid identity of Novel Readings — which is not really, or at least not just, a book blog, and not really, or not altogether, an academic blog — has probably limited its appeal, because for some bookish people there’s no doubt too much academic stuff here, while for some academics, there’s too much book talk (or, too much book talk that’s not sufficiently academic). So: what’s up for this winter term? Something old and something new. I’m doing another iteration of 19th-Century British Fiction (Dickens to Hardy), beginning, this week, with Bleak House, which I haven’t taught (or read) since 2013. I was so sad to read Hilary Mantel identifying Dickens as

So: what’s up for this winter term? Something old and something new. I’m doing another iteration of 19th-Century British Fiction (Dickens to Hardy), beginning, this week, with Bleak House, which I haven’t taught (or read) since 2013. I was so sad to read Hilary Mantel identifying Dickens as  I don’t want to leave the impression that frustration with the rigidity of academic practices is all I took away from my Louisville conference experience. There was definitely value for me in the work I put into my own paper, as well as in hearing and discussing the papers my co-panelists presented. So I thought I’d follow up

I don’t want to leave the impression that frustration with the rigidity of academic practices is all I took away from my Louisville conference experience. There was definitely value for me in the work I put into my own paper, as well as in hearing and discussing the papers my co-panelists presented. So I thought I’d follow up  Mendelsohn’s article was one of the sources I cited in my paper, in which I explored some questions about what we mean by “critical authority.” As he notes, once you move outside the academy degrees are neither a necessary nor a sufficient measure of the relevant expertise. But it’s not easy to pin down what does count, how authority is established, especially in a field of inquiry where there are no sure or absolute standards of judgment. Literary critics know that their authority is unstable because the history of criticism teaches us how judgments change over time, while simple experience shows us how much they differ among individuals. We can call variant assessments “gaffes” or “errors in individual taste,” as Mendelsohn does in his recent

Mendelsohn’s article was one of the sources I cited in my paper, in which I explored some questions about what we mean by “critical authority.” As he notes, once you move outside the academy degrees are neither a necessary nor a sufficient measure of the relevant expertise. But it’s not easy to pin down what does count, how authority is established, especially in a field of inquiry where there are no sure or absolute standards of judgment. Literary critics know that their authority is unstable because the history of criticism teaches us how judgments change over time, while simple experience shows us how much they differ among individuals. We can call variant assessments “gaffes” or “errors in individual taste,” as Mendelsohn does in his recent  If critical authority is not something you simply have but something you have to earn and maintain by your own participation in a dialogue — if it is best understood not so much as a top-down assertion of superiority (“the critic’s job,” Mendelsohn proposes in his recent review, “is to be more educated, articulate, stylish, and tasteful … than her readers have the time or inclination to be”) but as a process of establishing yourself as someone whose input into an ongoing conversation is sought and valued — that helps explain why “expertise” is such a tricky thing to define for a critic. Mendelsohn’s original formal training is as a classicist — despite his wide-ranging erudition and critical prestige, he would almost certainly not qualify for an academic position in any other field — but obviously he has written with considerable insight on a wide range of subjects, from Stendhal to Mad Men. That so many of us read Mendelsohn’s criticism with interest and attention no matter what he writes about is a sign that we have come to trust him, not as the last word on these subjects, but as someone who will have something interesting (“meaningful,” to use one of his key terms) to say about them. If we disagree with him, we are not challenging his authority but continuing the conversation — and in fact one thing I’ve been thinking a lot about is how little disagreement really matters to this kind of critical authority. If what we go to criticism for is a good conversation, then engaged disagreement can be seen as a sign of authority — a sign that you care enough about the critic’s perspective to tussle with it, if you like. I can think of a number of critics in venues from personal blogs to the New Yorker whose views I would not defer to, but which I want to know because they provoke me to keep thinking about my own readings — which (however definitive the rhetoric I too adopt in my more formal reviewing) I always understand to be provisional, statements of how something looked to me in that moment, knowing what I knew then, caring about what I cared about then.

If critical authority is not something you simply have but something you have to earn and maintain by your own participation in a dialogue — if it is best understood not so much as a top-down assertion of superiority (“the critic’s job,” Mendelsohn proposes in his recent review, “is to be more educated, articulate, stylish, and tasteful … than her readers have the time or inclination to be”) but as a process of establishing yourself as someone whose input into an ongoing conversation is sought and valued — that helps explain why “expertise” is such a tricky thing to define for a critic. Mendelsohn’s original formal training is as a classicist — despite his wide-ranging erudition and critical prestige, he would almost certainly not qualify for an academic position in any other field — but obviously he has written with considerable insight on a wide range of subjects, from Stendhal to Mad Men. That so many of us read Mendelsohn’s criticism with interest and attention no matter what he writes about is a sign that we have come to trust him, not as the last word on these subjects, but as someone who will have something interesting (“meaningful,” to use one of his key terms) to say about them. If we disagree with him, we are not challenging his authority but continuing the conversation — and in fact one thing I’ve been thinking a lot about is how little disagreement really matters to this kind of critical authority. If what we go to criticism for is a good conversation, then engaged disagreement can be seen as a sign of authority — a sign that you care enough about the critic’s perspective to tussle with it, if you like. I can think of a number of critics in venues from personal blogs to the New Yorker whose views I would not defer to, but which I want to know because they provoke me to keep thinking about my own readings — which (however definitive the rhetoric I too adopt in my more formal reviewing) I always understand to be provisional, statements of how something looked to me in that moment, knowing what I knew then, caring about what I cared about then. I’m not saying we can’t or shouldn’t defend our critical assessments, but awash as we are and always have been in such a variety of them, it would be naively arrogant at best and solipsistic at worst to imagine ourselves as “getting it right,” no matter who we are or where we publish. Blogging very often reflects that open-endedness in its tone, and its form is based on just the process Booth describes as “coduction”:

I’m not saying we can’t or shouldn’t defend our critical assessments, but awash as we are and always have been in such a variety of them, it would be naively arrogant at best and solipsistic at worst to imagine ourselves as “getting it right,” no matter who we are or where we publish. Blogging very often reflects that open-endedness in its tone, and its form is based on just the process Booth describes as “coduction”:

Some follow-up comments on academic blogging, prompted by comments on

Some follow-up comments on academic blogging, prompted by comments on