It is a wonder that a poem, let alone an unread poem, could have such a vigorous life in the culture–and its story still had decades to run before the present day. In the late twenty-first century, even as wars broke out in the Pacific (China against South Korea, Malaysia, the Philippines and others), vanished poem and vanished opportunities coalesced into a numinous passion for what could not be had, a sweet nostalgia that did not need a resolution . . . The Corona was more beautiful for not being known. Like the play of light and shadow on the walls of Plato’s cave, it presented to posterity the pure form, the ideal of all poetry.

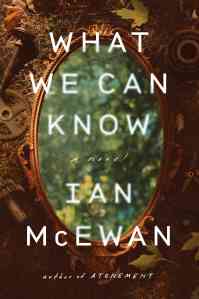

I really liked the first half of What We Can Know. McEwan is always a meticulous stylist, and the persona he sets up to narrate this part is easy to follow and, as an academic, a good proxy for McEwan’s own analytical mind. But what I liked most about it was the concept—for better and for worse, McEwan’s fiction is always highly conceptual, and so I think (and a chat about the novel with a friend today confirmed) our experience of reading him is always going to be strongly affected by whether we buy the concept or not, whether for whatever combination of readerly reasons it strikes us as engaging and convincing, or as a gimmick. In this case the scenario is an oddly optimistic post-apocalyptic one: its narrator, Tom Metcalfe, is an English professor, about 100 years in the future, living on a planet that has built its way back after significant but not utter destruction. McEwan uses this premise to turn our present into a past that can be contemplated historically. How might we think about our situation if we weren’t actually in it? is the thought experiment, and it leads to some thought-provoking and, for me at least, surprisingly stirring reflections from Tom about the period he has chosen to specialize in:

What brilliant invention and bone-headed greed. What music, what tasteless art, what wild breaks and sense of humour; people flying 2,000 miles for a one-week holiday; buildings that touched the cloud base; razing ancient forests to make paper to wipe their backsides. But they also spelled out the human genome, invented the internet, made a start on AI and placed a beautiful golden telescope a million miles out in space.

Then came what the future calls “the Derangement,” which led to wars and climate catastrophes; large sections of the earth’s landmasses have been submerged, leaving islands connected by variously perilous seas.

McEwan has rigged the game in favour of a cautious optimism, based on what he notes in this interview has historically been the case: societies, like nature, have the capacity to recover, to regenerate, to fill in, to accommodate and adapt. What I mean by “rigged the game” is that he protected us, and Earth, from complete devastation. The losses are vast, staggering, but there’s enough left–including, especially, enough information–that rebuilding is possible. Even of universities! Which in 2119 occupy literally (if perhaps not metaphorically) the highest ground. They even still have English departments, something that doesn’t always feel likely about the very near future, so it was nice to be imagining that in 2119 people still have jobs reading and teaching about poems and novels.

The poem that preoccupies Tom is one that was read aloud at a party in 2014 and then lost forever. The content and context of the poem make up a lot of What We Can Know, which in a way is like a futuristic version of A.S. Byatt’s Possession, dramatizing the romance of research–a quest for a lost truth, a heroic rescue mission carried out in archives that, in this case, can sometimes be accessed only by arduous and risky sea voyages–while also highlighting the inevitable futility of the effort to find out ‘what really happened.’ Archives are incomplete; evidence is missing or misleading; interpretation is fallible. Even the quantitatively overwhelming material left by inhabitants of the digital age is not enough to lead the most diligent researcher to the truth–as Tom eventually finds out.

The first half of the novel follows Tom’s effort to reconstruct the night of the poetry reading and then to find, if he possibly can, the long-lost poem itself, which has had an extraordinary afterlife in spite of, or perhaps because of, the absence of the poem itself. By its non-existence, it has become “a repository of dreams, of tortured nostalgia, futile retrospective anger and a focus of unhinged reverence.” “The imagined lords it over the actual,” Tom reflects; perhaps once found the poem would lose, rather than gain, significance. Wisely, no doubt, McEwan does not include even fragments of it: he says it was because early readers found his poetic attempts inadequate, but it seems fitting in any case that it remains always out of our reach. Does Tom ever find it, though? Well, that would a spoiler, wouldn’t it?

The second half of the novel offers a first-hand account of the poem’s origins, including backstory on all the figures in the poet’s life that Tom has obsessed over throughout his career. It is more conventional, high concept only in its relationship to the futuristic framing. It’s well done, though predictable and occasionally (I thought) a bit too contrived in some of its details. When I reached its rather pat ending, I found myself wondering if I had missed something that would be apparent on a re-reading of the whole novel: I think of how the early parts of Atonement, for example, vibrate with new meaning once you have read to the end, including not just the metafictional twist but also the way Briony’s fictionalization turns out to have incorporated advice you later learn she got from readers and editors. Tom’s version of the story is, I think it’s fair to say, an idealization, a kind of wishful thinking, a story that fits the evidence he has together to suit his vision of the people and events. It is inaccurate, not just because his information is copious but incomplete, but because what he wants to do (as Dorothea Brooke would put it, to reconstruct a past world, with a view to the highest purposes of truth!) is always already impossible. OK, I get it! I got that before I read the ‘real’ version—which is also, of course, inevitably partial, perhaps dubiously reliable. But do we learn something more specific about Tom’s version, are there specific things he gets wrong, or (to consider another possibility) is there evidence he mentions that undermines the version that makes up the novel’s second half? I didn’t notice any such clever moments, but there’s a lot I didn’t notice about Atonement on my first reading.

The second half of the novel offers a first-hand account of the poem’s origins, including backstory on all the figures in the poet’s life that Tom has obsessed over throughout his career. It is more conventional, high concept only in its relationship to the futuristic framing. It’s well done, though predictable and occasionally (I thought) a bit too contrived in some of its details. When I reached its rather pat ending, I found myself wondering if I had missed something that would be apparent on a re-reading of the whole novel: I think of how the early parts of Atonement, for example, vibrate with new meaning once you have read to the end, including not just the metafictional twist but also the way Briony’s fictionalization turns out to have incorporated advice you later learn she got from readers and editors. Tom’s version of the story is, I think it’s fair to say, an idealization, a kind of wishful thinking, a story that fits the evidence he has together to suit his vision of the people and events. It is inaccurate, not just because his information is copious but incomplete, but because what he wants to do (as Dorothea Brooke would put it, to reconstruct a past world, with a view to the highest purposes of truth!) is always already impossible. OK, I get it! I got that before I read the ‘real’ version—which is also, of course, inevitably partial, perhaps dubiously reliable. But do we learn something more specific about Tom’s version, are there specific things he gets wrong, or (to consider another possibility) is there evidence he mentions that undermines the version that makes up the novel’s second half? I didn’t notice any such clever moments, but there’s a lot I didn’t notice about Atonement on my first reading.

My friend liked the second part of the novel better than the first, and I can see why. There are certainly parts of Tom’s narrative that aren’t completely convincing, and there’s a somewhat stiff or chilly quality to his voice that we (both academics) somewhat ruefully agreed might be a deliberate part of his characterization as an academic. I did think, though, that there was something passionate about him, something sympathetically melancholy about his preoccupation with the past, wrapped though it is in the language of professional obligation and advancement. “I’ve spent a lifetime,” he says,

getting on intimate terms with people I can never meet, people who really existed and are therefore far more alive to me than characters in a novel. I have tried to embrace what is ‘beyond my reach in time.'”

He knows the past is inaccessible, but in retracing these lives, he feels a “fervent longing and melancholy” that is “my true sad sign of a last world that I have come to know too well.” All of us who study the past have got to recognize a bit of ourselves in that; what’s fresh in McEwan’s approach is that Tom’s past is our present, so even as we might resist his characterization of it, he also defamiliarizes it for us, giving us a chance to ask ourselves: is it really like that? What if we actually have it pretty good? “The Blundys and their guests” Tom observes,

lived in what we would regard as a paradise. There were more flowers, trees, insects, birds and mammals in the wild, though all were beginning to vanish. The wines the Blundys’ visitors drank were superior to ours, their food was certainly more delicious and varied and came from all over the world. The air they breathed was purer and less radioactive. Their medical services, though a cause of constant complaint, were better resourced and organized. They could have travelled from the Barn in any direction for hours on dry land.

OK, it looks good only by comparison with a world reshaped by global disasters, so while I have described the novel as shaped by optimism, I think it’s also fair to see that it also stands as a bracing kind of cautionary tale, a useful reminder that what we have is fragile, imperilled—that if it’s worth remembering nostalgically, it is also surely worth trying to preserve.

Well this review helps me decide about reading this one.

One of the interesting things about both of us being retired and so having to pare back our expenses has been that I’ve returned to a much stricter policy of waiting for a new book until the local public library can get it, and I wasn’t sure if I’d want to read What We Can Know when it’s finally my turn. I think I’m interested, but what you say about the second half will help pare back my expectations!

LikeLike

I’ll be interested to know if you (like my friend) actually like that half better. My book club chose this one for our December discussion, so I indulged in a hardcover, which I rarely do. It’s not just the expense: they are heavier and less comfortable to hold!

LikeLiked by 1 person

My response to this novel was also ambivalent. I found the two-part structure weakened rather than enhanced my appreciation of the Tom narrative, and much of it seemed contrived to me. And yet – there’s something about it it all that lingers in the mind after reading, as your quotations reminded me.

LikeLike