But this slight depression—what is it? I think I could cure it by crossing the channel, & writing nothing for a week . . . But oh the delicacy & complexity of the soul—for, haven’t I begun to tap her & listen to her breathing after all? A change of house makes me oscillate for days. And thats [sic] life; thats wholesome. Never to quiver is the lot of Mr. Allinson, Mrs. Hawkesford, & Jack Squire. In two or three days, acclimatised, started, reading & writing, no more of this will exist. And if we didn’t live venturously, plucking the wild goat by the beard, & trembling over precipices, we should never be depressed, I’ve no doubt, but already should be faded, fatalistic & aged.

You thought it was me who felt that way, right? But instead it is Woolf, feeling and thinking and, especially, thinking about feeling.

The parts I am most likely to bookmark as I am reading through the diaries are the ones about writing, the ones probably mostly already included in the Writer’s Diary Leonard compiled (I have it and have mostly read it, in the past, but am not cross-checking.) I do find Woolf the writer endlessly fascinating, especially now that she has / I have reached a point where she knows she is finally writing as herself, in her own way. “If this book [Jacob’s Room] proves anything,” she reflects,

it proves that I can only write along those lines, & shall never desert them, but explore further & further, & shall, heaven be praised, never bore myself an instant.

Imagine that: I bore myself constantly, especially when I’m writing in my own journal! By the end of Volume II of the published diary she is well along in Mrs. Dalloway (“in this book I have almost too many ideas,” she says, but excitedly, not with anxiety), and she is feeling it, not growing into her voice but now at last (her sense of it) finally using it, with a consciousness of freedom (“I’m less coerced than I’ve yet been,” she says about the writing process).

But at the risk of creating a dichotomy where there shouldn’t be one, Woolf the person is at least as interesting, partly because she is not so sure. She is thin-skinned, sensitive, doubting. She waits on tenterhooks for reviews, especially in the “Lit Sup,” where, she complains, “I never get an enthusiastic review . . . and it will be the same for Dalloway.” She is elated by a generous commentary from “Morgan” (E. M. Forster) and irritable about how long it takes for the Common Reader to get any notice at all—although we might wonder at her expectations: “out on Thursday,” she says petulantly, “this is Monday, & so far I have not heard a word about it, private or public.” Shouldn’t a genius be above this kind of fretting? But if courage is not the absence of fear but acting in spite of the fear, perhaps genius is not the absence of self-consciousness or doubt but writing exactly what you want in spite of those feelings, living venturously, trembling over precipices, braving depression—as long as you can bear it, anyway.

“This diary writing has greatly helped my style,” she says in November 1924; “loosened the ligatures.” I wrote before about how she seemed to be seeking or practising looseness through the relative formlessness of her entries. I’m into Volume III now, already done 1925 because that’s a very short year, and while there is still a lot of meeting and visiting and housekeeping, there are also still what seem clearly like practice sessions for her fiction, little set pieces like this one which, while in a way “just” records of something that happened, somehow do more, or go further:

“This diary writing has greatly helped my style,” she says in November 1924; “loosened the ligatures.” I wrote before about how she seemed to be seeking or practising looseness through the relative formlessness of her entries. I’m into Volume III now, already done 1925 because that’s a very short year, and while there is still a lot of meeting and visiting and housekeeping, there are also still what seem clearly like practice sessions for her fiction, little set pieces like this one which, while in a way “just” records of something that happened, somehow do more, or go further:

I am under the impression of the moment, which is the complex one of coming back home from the South of France to this wide dim peaceful privacy – London (so it seemed last night) which is shot with the accident I saw this morning & a woman crying Oh oh oh faintly, pinned against the railings with a motor car on top of her. All day I have heard that voice. I did not go to her help; but then every baker & seller did that. A great sense of the brutality & wildness of the world remains with me—there was this woman in brown walking along the pavement—suddenly a red film car turns a somersault, lands on top of her, & one hears this oh, oh oh.

And yet she still continues on “to see Ness’s new house,” which they go through “composedly enough,” as we all do, if it isn’t our particular catastrophe.

I’m looking forward to 1926, when Mrs. Dalloway is published. In her introduction to Volume III, Olivia Laing notes that it covers “perhaps the most fruitful, satisfying years” of Woolf’s life:

[it] opens as Woolf is revising her fourth novel, Mrs. Dalloway, and her first volume of criticism, The Common Reader, and closes as she is editing The Waves. In the intervening years she writes To the Lighthouse, Orlando, and A Room of One’s Own, plus a formidable battalion of essays and reviews.

Now that’s a streak. Does she shake off those worries about how her work will be received, I wonder? I suspect not, as I know from other research I’ve done that years later she was pretty fretful about both the writing and the reception of The Years. In 1925, she’s daring to imagine, though, that she “might become one of the interesting—I will not say great—but interesting novelists.” As she turns her full attention to To the Lighthouse, she’s also rethinking whether she’s a novelist at all: “I have an idea that I will invent a new name for my books to supplant ‘novel” A new——by Virginia Woolf. But what? Elegy?”

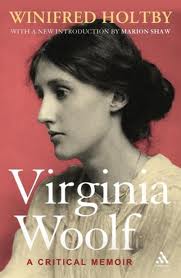

Winifred Holtby’s chapter on this period of Woolf’s life is called “The Adventure Justified”: “she was more sure now,” Holtby writes, “both of herself and of her public. She dared take greater risks with them, confident that they would not let her down.” It’s a wonderful chapter, rising almost to ecstasy about Woolf’s achievement in To the Lighthouse:

Winifred Holtby’s chapter on this period of Woolf’s life is called “The Adventure Justified”: “she was more sure now,” Holtby writes, “both of herself and of her public. She dared take greater risks with them, confident that they would not let her down.” It’s a wonderful chapter, rising almost to ecstasy about Woolf’s achievement in To the Lighthouse:

Its quality is poetic; its form and subject are perfectly fused, incandescent, disciplined into unity. It is a parable of life, of art, of experience; it is a parable of immortality. It is one of the most beautiful novels written in the English language.

But in November 1925, Woolf is feeling faded and fatalistic: “Reading & writing go on. Not my novel though. And I can only think of all my faults as a novelist & wonder why I do it.”

What an intriguing and emotionally oriented review of Virginia Wolf’s writing. You are luring me in to reading her diaries. I’ve read all of her novels ( I think), but have never attempted the diaries. Maybe it’s time.

LikeLike

Thanks, Daphna. I try just to write whatever comes to me for these posts and not second-guess myself, as so much other writing I do has to meet other people’s needs or standards. I enjoy never really knowing what I will end up talking about. 🙂

The new Granta edition of the diaries is superb, I think.

LikeLiked by 1 person