That instant, the memory of a long-lost word rises up in her, cut in half, and she tries to grab hold of it. She had learned that, in times past, there had been a word, a Hanja word . . . by which people had referred to the half-light just after the sun sets and just before it rises. A word that means having to call out in a loud voice, as the person approaching from a distance is too far away to be recognized, to ask who they are . . . This eternally incomplete, eternally unwhole word stirs deep within her, never reaching her throat.

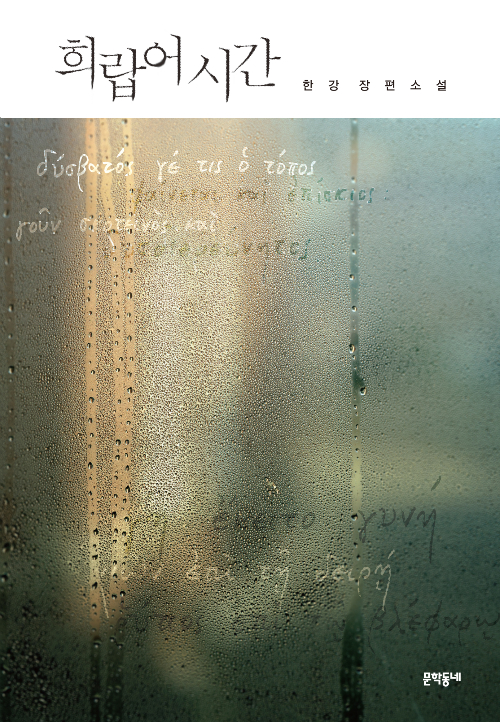

I had looked at Greek Lessons more than once in the bookstore before Han Kang won the Nobel Prize, partly because she’s a writer I’d read about as far back as J. C. Sutcliffe’s excellent review of The Vegetarian in Open Letters Monthly, and partly because the title kept catching my eye: what could a novel called Greek Lessons be about? Language, certainly, and lessons, both of which already hint at themes of (mis)communication, translation, and (mis)understanding. It was the Nobel Prize that finally tipped the balance for me to try one of her books, and my curiosity about its (to me) promising title that made me choose Greek Lessons.

I’m not sure how I feel about Greek Lessons now that I’ve read it, and I’m not sure if I will read any of Han Kang’s other novels. I suspected going in that it was not exactly the kind of novel I typically like, but I often try to test these expectations, to challenge myself a bit. It’s funny, maybe, that a novel as quiet as Greek Lessons could be a challenge, but I often struggle to engage with novels that are more mood or experience than plot and character, that are evasive or elliptical—and Greek Lessons is all of these things.

It could hardly be more explicit or expository, of course, and still preserve its “aboutness” (a librarian’s term I find so useful!). An incredibly simple story, on the surface, about a relationship slowly and haltingly developing between a man who is losing his sight—the Greek teacher—and a woman who has lost her voice—one of his students—it is also a delicately profound, wistful exploration of gaps and silences and the struggle for expression, the ways language clarifies but also obscures our feelings and our meaning. One of the clearest accounts of this comes fairly late in the novel, when she is reflecting on why she stopped speaking:

She knows that no single experience led to her loss of language.

Language worn ragged over thousands of years, from wear and tear by countless tongues and pens. Language worn ragged over the course of her life, by her own tongue and pen. Each time she tried to begin a sentence, she could feel her aged heart. Her patched and repatched, dried-up, expressionless heart. The more keenly she felt it, the more fiercely she clasped the words. Until all at once, her grip slackened. The dulled fragments dropped to her feet. The saw-toothed cogs stopped turning. A part of her, the place within her that had been worn down from hard endurance, fell away like flesh, like soft tofu dented by a spoon.

The paradox here, of course, is that Han Kang’s own language is expressive and evocative: surely that passage, ostensibly about the failure or abandonment of language, is its own rebuttal?

But other parts of the novel are more fragmented, especially (and again this felt paradoxical) as these two wounded, lost, and lonely people move closer to each other:

At one moment, moving your index finger over the flesh of my shoulder, you wrote.

Woods, you wrote, woods.

I waited for the next word.

Realizing that no next word was coming, I opened my eyes and peered at the darkness.

I saw the pale blur of your body in the darkness.

We were very close then.

We were lying very close and embracing each other.

It is perhaps a failing in me—in my reading habits, or my reading sensibility, or the way I have trained as a reader—that I find this kind of writing portentous rather than captivating or moving. It provokes a kind of impatience in me; it distracts me with attention to the writing, rather than immersion in the written.

And yet overall I was captivated by Greek Lessons, not so much by its particulars as by the melancholy space it created. Ordinarily I prefer some forward momentum in a novel (both cause and effect of my specializing in the 19th-century novel for so long!). What Greek Lessons offers instead, or this is how it felt to me, is a kind of time out, from that fictional drive and also from the busy world that these days overwhelms us with “content” and noise. In the intimacy of the portrayal of these two people, both of whom are retreating from the world partly by choice but mostly from the cruelty of their circumstances, there is some recognition of how hard it is to be ourselves, to be authentic, to see each other. The quiet sparseness of Han Kang’s writing could be seen as an antidote to the pressure to perform who we are and to insist on making space for ourselves out there. (Pressured by her therapist to break her silence, the woman thinks, “she still did not wish to take up more space.”)

And yet overall I was captivated by Greek Lessons, not so much by its particulars as by the melancholy space it created. Ordinarily I prefer some forward momentum in a novel (both cause and effect of my specializing in the 19th-century novel for so long!). What Greek Lessons offers instead, or this is how it felt to me, is a kind of time out, from that fictional drive and also from the busy world that these days overwhelms us with “content” and noise. In the intimacy of the portrayal of these two people, both of whom are retreating from the world partly by choice but mostly from the cruelty of their circumstances, there is some recognition of how hard it is to be ourselves, to be authentic, to see each other. The quiet sparseness of Han Kang’s writing could be seen as an antidote to the pressure to perform who we are and to insist on making space for ourselves out there. (Pressured by her therapist to break her silence, the woman thinks, “she still did not wish to take up more space.”)

The novel isn’t consoling, though: it’s deeply sad, almost tragic. Even the connection the two people achieve feels less like a triumph or a happy ending and more like a concession: this is the best we can do. “It felt like I was being kissed by time,” he thinks;

Each time our lips met, the desolate darkness gathered.

Silence piled up like snow, snow the eternal eraser.

Mutely reaching our knees, our waists, our faces.