In 19th-Century British Fiction, we’re wrapping up our discussions of Great Expectations this week. I’ve written before about teaching this novel. Here’s a bit from that post, in which I focus on Pip’s moving speech to Estella after he learns Magwitch is his true benefactor and Estella, though she “cannot choose but remain part of [his] character, part of the little good in [him], part of the evil,” is not destined for him after all:

Contemporary novelists are often described as “Dickensian,” usually for writing long, diffuse novels with lots of plots and characters and a bit more emotional exhibitionism than is the norm in ‘serious’ fiction. I rarely think they deserve the label, because to me it’s moments such as this one, combining dense symbolic allusiveness, rhythmic and evocative language, high sentiment, and urgent moral appeal–all bordering on the excessive, even ridiculous, but, at their best, not collapsing into it–that distinguish Dickens from other novelists. I’m not sure any modern novelist takes such risks.

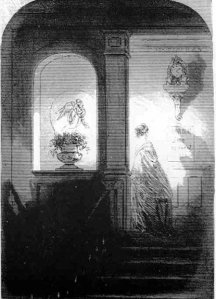

I’ve been thinking even more this time about the “risks” Dickens takes, his excesses of both language and imagination. They press us so far beyond the realistic, in almost any sense of that elusive term. Take Miss Havisham, for instance. There’s really no excuse for Miss Havisham: to be confronted with her is to be challenged to forget plausibility–to abandon, not just suspend, disbelief. Less a woman than a grotesque embodied symbol of life without love, a kind of moral and emotional zombie, she is also a key agent of the plot, with completely commonplace control over money and property. What kind of undead figure has its own lawyer? So she exists in a strange liminal zone between human and inhuman, until woken to her own tragedy, and the tragedy she has spawned in Estella (“I am what you have made me!”) by witnessing Pip’s suffering:

‘What have I done! What have I done!’ She wrong her hands, and crushed her white hair, and returned to this cry over and over again. ‘What have I done!’

I knew not how to answer, or how to comfort her. That she had done a grievous thing in taking an impressionable child to mould into the form that her wild resentment, spurned affection, and wounded pride, found vengeance in, I knew full well. But that, in shutting out the light of day, she had shut out infinitely more; that, in seclusion, she had secluded herself from a thousand natural and healing influences; that her mind, brooding solitary, had grown diseased, as all minds do and must and will reverse that reverse the appointed order of their Maker; I knew equallywell. And could I look upon her without compassion, seeing her punishment in the ruin she was, in her profound unfitness for this earth on which she was placed, in the vanity of sorrow which had become a master mania, like the vanity of penitence, the vanity of remorse, the vanity of unworthiness, and other monstrous vanities that have been curses in this world?

Miss Havisham cannot survive this ordeal by moral revelation, which, in truly Dickensian fashion, leads to a literal conflagration of the “rottenness” and “ugly things” that made up her perverted identity. Pip’s ability to feel compassion for this creature who has captured and ruined his own best hopes and feelings is one of the signs that he is on his way to being, not the Pip who turned his back on Joe, but the Pip who has the ethical sensibility to narrate Great Expectations.

In Victorian Sensations, we’ve finished with The Woman in White and are nearly done with Lady Audley’s Secret. When I wrote about this novel before (in the context of a different course), I remarked, “It is always a bit discouraging to me how popular this novel is with my students, full as it is of cheap tricks and thoughtless language.” My feelings are a bit more complicated this time. Lady Audley’s Secret is certainly in the category of ‘novels I teach largely for reasons other than their overt literary merit’: even acknowledging the difficulty of defining that quality with any specificity, I do chafe at the excesses of Braddon’s writing–they aren’t the imaginative or linguistic excesses of Dickens but the novelistic equivalent of using a lot of exclamation points or TYPING IN ALL CAPS in an email. “We get it!” I want to say (no doubt, of course, many readers feel the same about Dickens). Here’s a sample, for instance, from a conversation between Our Hero, Robert Audley, and his BFF George Talboys. Robert has recently convinced George to come and visit Audley Court to meet his uncle, Sir Michael Audley, and his pretty, young, golden-haired new wife. George has been feeling melancholy since learning that his pretty golden-haired wife died (hmmmm) just before his return from three years in Australia.

‘I’m not a romantic man, Bob,’ he would say sometimes, ‘and I never read a line of poetry in my life that was any more to me than so many words and so much jingle; but a feeling has come over me since my wife’s death, that I am like a man standing upon a long low shore, with hideous cliffs frowning down upon him from behind, and the rising tide crawling slowly but surely about his feet. It seems to grow nearer and nearer every day, that black, pitiless tide; not rushing upon with with a great noise and a might impetus, but crawling, creeping, stealing, gliding towards me, ready to close in above my head when I am least prepared for the end.’

As Miley Cyrus might say, d’ya think something bad might lie in his future? And is it just me, or is it hard to maintain literary decorum with a hero named ‘Bob,’ as in this immortal line, “‘I trust in your noble heart, Bob'”?!

And yet there are sections of this novel that are as good as most others I’ve read. In particular, this time through, I was struck by how effectively Braddon evokes the psychological restlessness, even instability, of Lady Audley as she waits for what she hopes (or possible, just a little, fears) is the news of Robert’s death. Spoiler alert: she has double-locked his door at the inn and then set the place on fire, and we get this striking image as she leaves the scene of the crime:

Sir Michael’s wife walked towards the house in which her husband slept, with the red blaze lighting up the skies behind her, and with nothing but the blackness of the night before.

It’s a nice touch to identify her by the status she has risked so much to achieve, but also to hint, with the “blackness” ahead of her, that despite the devastation she has now wrought, her future contains nothing “but the blackness of the night.” Then follows a long chapter of waiting, a damp listless day with no outlet for Lady Audley’s energies by “to wander up and down [the] monotonous pathway” in the courtyard of her luxurious home. The day ekes itself out:

Sir Michael’s wife [again, nice] still lingered in the quadrangle; still waited for those tidings which were so long coming.

It was nearly dark. The blue mists of evening had slowly risen from the ground. The flat meadows were filled with a grey vapour, and a stranger might have fancied Audley Court a castle on the margin of a sea. [This image ominously echoes Robert Audley’s earlier dream of Audley Court ‘rooted up . . . standing bare and unprotected . . . threatened by the rapid rising of a boisterous sea, whose waves seemed gathering upward to descend and crush the house he loved.’] Under the archway the shadows of fast-coming night lurked darkly; like traitors waiting for an opportunity to glide stealthily into the quadrangle. [Again, this image harkens back to an earlier one, in which the history of Audley Court is associated with secrets and conspiracies. Traitors to what, we might ask at this point?] Through the archway a patch of cold blue sky glimmered faintly, streaked by one line of lurid crimson, and lighted by the dim glitter of one wintry-looking star. [In Robert’s dream, the only stars are those in the eyes of ‘my lady, transformed into a mermaid, beckoning his uncle to destruction. See how completely this very suspenseful moment builds on images and ideas from earlier in the novel?] Not a creature was stirring in the qudrangle but the restless woman, who paced up and down the straight pathways [ones she has, metaphorically, strayed from quite a bit by this point!], listening for a footstep, whose coming was to strike terror to her soul. She heard it at last!–a footstep in the avenue upon the other side of the archway. But was it the footstep?

To find out whose footstep it was, you’ll have to read the book yourself! My point here is that this seems to me very effective writing–effective, that is, as a means to its end, which is suspense, to be sure (and if we are too easily dismissive of plot when we make up the terms for ‘literary merit,’ what, if any, room do we make for suspense?) but also the elaboration of a range of images, symbols, and ideas–that Lady Audley’s very presence on those “straight pathways,” for instance, represents a catastrophe for the ‘house’ of Audley. This section also effectively complicates the previously two-dimensional morality of the novel: the anxious activity of Lady Audley shows her to be more than “just” a villain, no matter how resolutely Robert seeks to contain her in that role. An actress, an infiltrator, a subversively ambitious woman who will not stop at anything to keep the gains she has made–but still capable of feeling “terror” in her soul as she awaits confirmation of her crime. Shortly, she will also give an account of her life and motives that forces the reader (if not necessarily her audience within ‘story space’) to entertain the possibility that she acts in self defense, or at least, like Becky Sharp (an obvious progenitor), she is simply using the limited means available to her, as a woman in a profoundly patriarchal world, to get–and stay–ahead. It’s provocative stuff, and entertaining, and if it’s inconsistently crafted (and, as I tend to think, inconclusively ‘argued’), it succeeds at what it seems to set out to do. I suppose that’s one definition of ‘well-written.’ Indeed, that’s George Henry Lewes’s definition: he describes Jane Austen as the “greatest artist that has ever written, using the term to signify the most perfect mastery over the means to her end.”

And that idea of “mastery over the means to her end” brings me to something I hope to write more specifically about soon, namely, how fast I think we (should) move, when the question of “literary merit” comes up, from the aesthetic to the ethical. Even supposing we could arrive at some resilient definition of good writing, it would have to (I think) make something like Lewes’s dodge here from the suggestion of universality implied in “mastery” to the issue of writing suited to a particular “means.” That’s why we can call both Dickens and Ian McEwan “good” (accomplished, skilfull, successful) writers. But at some point in that discussion, the question surely arises: how do we judge the ends? As Orwell famously said, “the first thing we demand of a wall is that it shall stand up”:

If it stands up, it is a good wall, and the question of what purpose it serves is separable from that. And yet even the best wall in the world deserves to be pulled down if it surrounds a concentration camp. In the same way it should be possible to say, “This is a good book or a good picture, and it ought to be burned by the public hangman [well, OK, that makes me uncomfortable, though he does go on to suggest this book burning may be a mental, rather than a literal, result]. Unless one can say that, at least in imagination, one is shirking the implications of the fact that an artist is also a citizen and a human being.