After college, for a period of two years and eight months, the “real world” became a room at Beth Israel Hospital and Tom’s one-bedroom apartment in Queens. Never mind that I was starting out at a glamorous job in a midtown skyscraper; it was these quieter spaces that taught me about beauty, grace, and loss—and, I suspected, about the meaning of art.

When in June of 2008, Tom died, I applied for the most straightforward job I could think of in the most beautiful place I knew. This time, I arrive at the Met with no thought of moving forward. My heart is full, my heart is breaking, and I badly want to stand still awhile.

The “glamorous job” Patrick Bringley turned his back on was at the New Yorker; the job he took after his brother Tom’s death was as a guard at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, a job he held for a decade. Reading All the Beauty in the World, his moving, meditative, wide-ranging reflections on his experience standing for thousands of hours among some of the world’s greatest treasures, I wondered if he always had it in the back of his mind that there would be a book in it someday. It’s hard to imagine anyone both literary and ambitious enough to work at the New Yorker not having that thought! This was not in any way a cynical notion on my part; if anything, I feel lucky that, with whatever long-term intentions, Bringley clearly thought and wrote down enough during his time in the museum that I could now read about it and be guided by him towards insights into what art can mean and do for us if we just stand still long enough to let it.

One of Bringley’s central insights is that art’s power comes from what it shows us about the most commonplace, and thus most human, parts of life. “Much of the greatest art,” he observes,

seeks to remind us of the obvious. This is real, is all it says. Take the time to stop and imagine more fully the things you already know. Today my apprehension of the awesome reality of suffering might be as crisp and clear as Daddi’s great painting.* But we forget these things. They become less vivid. We have to return as we do to paintings, and face them again.

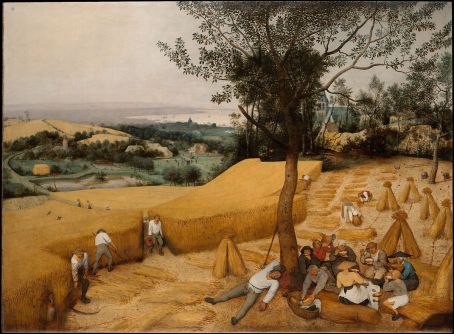

It isn’t always suffering and death that art invites us to stand and face. One of Bringley’s favorite paintings is Pieter Bruegel’s The Harvesters, which shows, in the foreground, a little group of peasants on their lunch break:

Looking at Bruegel’s masterpiece I sometimes think: here is a painting of literally the most common thing on earth. Most people have been farmers. Most of these have been peasants. Most lives have been labor and hardship punctuated by rest and the enjoyment of others. It is a scene that must have been so familiar to Pieter Bruegel it took an effort to notice it. But he did notice it. And he situated this little, sacred, ragtag group at the fore of his vast, outspreading world.

“I am sometimes not sure,” Bringley adds, “which is the more remarkable: that life lives up to great paintings, or that great paintings live up to life.”

The individual sections of All the Beauty in the World are organized, more or less, around Bringley’s assignments to particular rooms or wings or exhibits; the larger framing is his gradual reconciliation, if that’s the right word, with the “real world” outside the museum as he learns to live with Tom’s loss. Both the people he works with (who come from all parts of the world and all have their own stories about how they came to be standing guard over Van Gogh’s Irises or the tomb of Perneb) and the people he encounters as visitors all play a part in this emotional journey, but it is the art that matters the most, in ways that are better suited to samples than summaries. Here, for instance, is Bringley’s description of a silk scroll hand-painted by Guo Xi, a “Northern Song Dynasty” master:

The individual sections of All the Beauty in the World are organized, more or less, around Bringley’s assignments to particular rooms or wings or exhibits; the larger framing is his gradual reconciliation, if that’s the right word, with the “real world” outside the museum as he learns to live with Tom’s loss. Both the people he works with (who come from all parts of the world and all have their own stories about how they came to be standing guard over Van Gogh’s Irises or the tomb of Perneb) and the people he encounters as visitors all play a part in this emotional journey, but it is the art that matters the most, in ways that are better suited to samples than summaries. Here, for instance, is Bringley’s description of a silk scroll hand-painted by Guo Xi, a “Northern Song Dynasty” master:

Ink on silk is an unforgiving medium; there are no do-overs; he couldn’t rub out and paint over his mistakes as the old masters could do with oils. My eyes can trace every stroke Guo made in AD 1080. No part of his artistry is hidden from me, nothing submerged under overlapping layers. According to Guo’s son, the master’s regular practice was to meditate several hours, then wash his hands and execute a painting as if with a single sweep of his arm . . . What this picture has afforded for a thousand years it affords today. My eyes travel the same old routes, past the fishermen in their small, still boats, the bare autumnal trees, the peddlers and their pack mule, the rock croppings, the stooped old men ascending a hill, and into the mountains shrouded in mist. It is achingly beautiful . . . I am happy to be inside this picture, so clearly a melding of nature and the artist’s mind. Guo himself feels like my intimate . . .

Here he is being won over, after long skepticism about the Impressionists, to the magic of Monet’s Vétheuil in Summer:

I see a village and a river and the village’s reflection suspended in river water, only in Monet’s world there is no such thing as sunlight really, just color. Monet has spread around the sunlight color, like the goodly maker of his little universe. He has spread it, splashed it, and affixed it to the canvas with such mastery that I can’t put an end to its ceaseless shimmering. I look at the picture a long time, and it only grows more abundant; it won’t conclude.

Monet, I realize, has painted that aspect of the world that can’t be domesticated by vision—what Emerson called the “flash and sparkle” of it, in this case a million dappled reflections rocking and melting in the waves . . . Monet’s picture brings to mind one of those rarer moments where every particle of what we apprehend matters—the breeze matters, the chirping of birds matters, the nonsense a child babbles matters—and you can adore the wholeness, or even the holiness, of that moment.

With regret, I have left out some parts of this passage, because it is quite long, but I loved every word of it. One more, from Bringley’s encounter with a “nkisi, or power figure, made by the Songye people of what is today the Democratic Republic of the Congo”:

Above all, I can see the extraordinary geometry the wood-carver achieved in his effort to make the nkisi supernatural. This artist faced a tremendous formal challenge, I realize. Unlike Guo’s scroll or Monet’s painting, his sculpture wasn’t an imitation or a depiction of anything else. It wasn’t meant to look like a divine being; it was the divine being and, as such, had to appear as though it existed across a chasm from ordinary human efforts. It had to look a bit like a newborn baby looks . . . a new, miraculous, self-insistent whole.

. . . More than just dazzled, I am moved. With its eyes softly shut, the nkisi has a powerful air of inwardness, as though summoning the will to take on perilous forces closing in on it . . . it had to be this magnificent to push back.

There is much more, ranging across the breadth of the museum’s collections. Although I learned a lot from Bringley’s explanations of specific artefacts, they are (almost) beside the point, as these examples show: the interest and impact of the book comes mostly from his personal interactions—emotional and intellectual—with the works of art. It is an idiosyncratic kind of art appreciation, perhaps, though well-informed (he has done his research, in and out of the museum) and open-minded, but I think Bringley would argue that this is also the best kind.

As the years pass, all this time spend standing still gradually brings Bringley back in touch with the movement of life itself. “Grief,” he aptly observes,

is among other things a loss of rhythm. You lose someone, it puts a hole in your life and for a time you huddle down in that hole. In coming to the Met, I saw an opportunity to conflate my hole with a grand cathedral, to linger in a place that seemed untouched by the rhythms of the everyday. But those rhythms have found me again, and their invitations are alluring. It turns out I don’t wish to stay quiet and lonesome forever.

One sign of his revitalization is, paradoxically, that art begins to lose its hold on him. Looking at a painting of a mother and child by Mary Cassatt, he is overcome with its beauty: “for the first time in a long time, I simply adore.” He is saddened by his realization that this total absorption in a work of art has become less frequent for him:

Strangely, I think I am grieving for the end of my acute grief. The loss that made a hole at the center of my life is less on my mind than sundry concerns that have filled the hole in. And I suppose that is right and natural, but it’s hard to accept.”

All grievers probably recognize this reluctance to admit that time simply will not stand still with you and your sorrow (I’m reminded yet again of Denise Riley—”The dead slip away, as we realize that we have unwillingly left them behind us in their timelessness—this second, now final, loss”). Life is movement, and most of us step back into the current again at some point, changed but persisting. “Sometimes,” Bringley concludes,

life can be about simplicity and stillness, in the vein of a watchful guard amid shimmering works of art. But it is also about the head-down work of living and struggling and growing and creating.

And so he leaves this job too. From now on when he returns to the museum it will be as a visitor, just another person stepping inside for a moment to be reminded of the obvious, and to be reassured

And so he leaves this job too. From now on when he returns to the museum it will be as a visitor, just another person stepping inside for a moment to be reminded of the obvious, and to be reassured

that some things aren’t transitory at all but rather remain beautiful, true, majestic, sad, or joyful over many lifetimes—and here is the proof, painted in oils, carved in marble, stitched into quilts.

How I wish I could walk out the door right now and take him up on his closing advice about the best time to visit (“come in the morning . . . when the museum is quietest”). I used to visit the Met regularly myself: as a graduate student at Cornell, I took advantage of my (relative) proximity to the city to get season tickets to the Metropolitan Opera (a dream come true for a long-time listener to their Saturday afternoon broadcasts) and as often as I could, I worked in a museum visit as well. There is never enough time to take in everything you want to see—Bringley had a decade, thousands of hours, and will still be going back, after all! I often feel, in art galleries, that I never know enough to get the most out of them, but Bringley has not just inspired me but given me new confidence. “You’re qualified to weigh in on the biggest questions artworks raise,” he says in his closing peroration:

So under the cover of no one hearing your thoughts, think brave thoughts, searching thoughts, painful thoughts, and maybe foolish thoughts, not to arrive at right answers but to better understand the human mind and heart as you put both to use.

I like that idea of how to be in a museum—and I loved this book.

*You can find links to all the works Bringley references here. Some of them, for copyright reasons, can’t be downloaded, which is why my inserted images (all public domain) don’t 100% correspond to the examples I’ve quoted from the book.

Maybe it had something to do with my footwear, but this time it was fireworks, what A. S. Byatt calls “the kick galvanic.” It reminded me that all of art rests in the gap between that which is aesthetically pleasing and that which truly captivates you. And that the tiniest thing can make the difference.

Maybe it had something to do with my footwear, but this time it was fireworks, what A. S. Byatt calls “the kick galvanic.” It reminded me that all of art rests in the gap between that which is aesthetically pleasing and that which truly captivates you. And that the tiniest thing can make the difference. What I didn’t like: Optic Nerve felt really miscellaneous. Its unifying force is Gainza herself, or the narrating version of her, I suppose, but I often found myself puzzled over what else bound together the specific elements she included in each chapter. Sometimes I could see it, or sense it (the chapter about her brother and El Greco, for instance, which turned on ideas about religion, and – I think – on tensions between ascetism and sensuality), but most of the time it seemed random. Was I not reading or thinking hard enough, or was that fragmentation deliberate? Maybe the idea was precisely to scatter our focus, or to reflect the ways our lives are not in fact neatly organized around common themes–or to match her commentary on art, which emphasizes that we should, or always do, feel first and think later. I would have liked a bit of guidance about this from the book itself.

What I didn’t like: Optic Nerve felt really miscellaneous. Its unifying force is Gainza herself, or the narrating version of her, I suppose, but I often found myself puzzled over what else bound together the specific elements she included in each chapter. Sometimes I could see it, or sense it (the chapter about her brother and El Greco, for instance, which turned on ideas about religion, and – I think – on tensions between ascetism and sensuality), but most of the time it seemed random. Was I not reading or thinking hard enough, or was that fragmentation deliberate? Maybe the idea was precisely to scatter our focus, or to reflect the ways our lives are not in fact neatly organized around common themes–or to match her commentary on art, which emphasizes that we should, or always do, feel first and think later. I would have liked a bit of guidance about this from the book itself.

Have any of you watched any of the videos produced for

Have any of you watched any of the videos produced for