Stackhouse was no poet, no artist, and his literary tastes were unsophisticated. But he wrote for himself, not posterity, and he valued the notebook enough to fill more than three hundred pages, and to invite friends and family to make their notes in it too. His observations might be of consequence to no-one but himself, but isn’t it a happy thought that such documents can survive for centuries, intimate memorials to their owners’ preoccupations—unremarkable, hardly read, yet every one unique?

I finished Roland Allen’s The Notebook: A History of Thinking on Paper yesterday and decided it deserved more attention than I gave it in my round-up of my reading week reading. It just contains so much that’s interesting, even inspiring! I will be honest and say that I was not equally enthralled by every section, but that’s more a reflection of their variety, as they cover many of very wide-ranging uses to which the humble notebook has been put over the years, than of any fault in Allen’s account. I couldn’t possibly go through the whole array, so I will just offer some samples.

Allen begins with a survey of how people kept track of things before notebooks, including wax tablets and scrolls, and then explains the surprisingly fascinating relationship between the earliest paper notebooks and the needs and practices of accountants in medieval Florence:

Bookkeeping’s arrival had unexpected consequences. The new science of accountancy demanded notebooks in such a variety of sizes and shapes—giornale, memoriale, quaderni, squartofogli—and in such quantities, that as production boomed, they spilled out into every other sphere of Florentine life, sparking imaginations and inspiring new uses.

He devotes a chapter to The Book of Michael of Rhodes, Venice 1434, a voluminous notebook kept by an otherwise obscure sailor in the Venetian fleet who eventually rises through the ranks: it contains records of his voyages, abundant evidence of his fascination with mathematics, information about fitting out ships, all kinds of sketches and drawings, and much more. A more famous notebook keeper was Leonardo da Vinci, who “filled his notebooks at the rate of about a thousand pages a year, all obsessively covered with drawings, diagrams and idiosyncratic mirror handwriting”—but Allen makes the case that the notebooks of Leonardo’s friend Pacioli had more impact, as it was Pacioli who introduced the concept of double-entry bookkeeping, which “would dominate first Europe and then the world.”

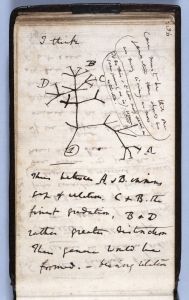

My epigraph for this post comes from the chapter on common-place books; there is also one on seafaring logs and one on the remarkable Visboek, or Fishbook, created by the Dutchman Adriaen Coenen in the 1570s. A chapter on travelers’ notebooks highlights Patrick Leigh Fermor and Bruce Chatwin; one on mathematics of course focuses on Newton. The most famous naturalist to keep notebooks was Charles Darwin, and Allen’s remarks about his process exemplify the connections he makes throughout the book between writing and thinking:

My epigraph for this post comes from the chapter on common-place books; there is also one on seafaring logs and one on the remarkable Visboek, or Fishbook, created by the Dutchman Adriaen Coenen in the 1570s. A chapter on travelers’ notebooks highlights Patrick Leigh Fermor and Bruce Chatwin; one on mathematics of course focuses on Newton. The most famous naturalist to keep notebooks was Charles Darwin, and Allen’s remarks about his process exemplify the connections he makes throughout the book between writing and thinking:

The transmutation notebooks are some of the most famous in the history of science, and there can’t be a clearer example of the notebook’s intellectual potential than Darwin’s story. Scratching quick, incoherent notes onto their tiny pages, he had used his field notebooks to prompt observation, interrogation and judgment of what he saw. Back on board the Beagle, Darwin turned these raw materials—just one hundred thousand telegraphic words—into nearly two thousand pages of systematic scientific notes, and an evocatively detailed diary. Then, in the ‘Red Notebook’ and its successors, he processed the arguments and ideas which would, in the six books he published in the decade after his voyage, make him one of the era’s most respected scientists—and then, in On the Origin of Species, change the way we think of life. All germinating from a pile of field notebooks that fit comfortably into a shoebox.

What’s distinctive here, of course, is focusing on notebooks themselves as enabling devices for Darwin’s achievements—Allen draws our attention over and over, as he makes his way through his many topics (including, besides the ones already mentioned, authors’ notebooks, recipe collections, police notebooks, patient diaries, and more) to the importance of the flexibility and portability of notebooks, the opportunities they create for in the moment as well as reflective writing, data collection as well as analysis and synthesis. The simple point that they can be carried with us and require so little else to do this work for us, or to support our work, is what matters: this is what was initially transformative and continues to be endlessly appealing, even in this electronic era. In the chapter on “journaling as self-care” Allen discusses the strong evidence for the value of “expressive writing” for helping to heal trauma (he also touches on the reasons that note-taking by hand seems to be more effective for learning during lectures).

What’s distinctive here, of course, is focusing on notebooks themselves as enabling devices for Darwin’s achievements—Allen draws our attention over and over, as he makes his way through his many topics (including, besides the ones already mentioned, authors’ notebooks, recipe collections, police notebooks, patient diaries, and more) to the importance of the flexibility and portability of notebooks, the opportunities they create for in the moment as well as reflective writing, data collection as well as analysis and synthesis. The simple point that they can be carried with us and require so little else to do this work for us, or to support our work, is what matters: this is what was initially transformative and continues to be endlessly appealing, even in this electronic era. In the chapter on “journaling as self-care” Allen discusses the strong evidence for the value of “expressive writing” for helping to heal trauma (he also touches on the reasons that note-taking by hand seems to be more effective for learning during lectures).

The only place where Allen’s enthusiasm for the many uses people have made of notebooks since their first appearance seems to flag is in his chapter on bullet journaling. He begins with an account of Ryder Carroll, who developed what is now a widely known and used system for organizing his time and tasks: “ Like the Florentine accountants, Renaissance artists and early modern scientists before him,” Allen says, “he’d come to understand his notebook as a crucial tool for the mind, a way to turn intangible thoughts into more concrete written ideas that could more easily be manipulated.” So far so good, but once Carroll’s system becomes popular and highly commercial, and “bullet journaling was everywhere,” Allen starts to get a bit sniffy about it—especially about the “huge online community of bullet journalists who took to social media to celebrate and share their own journals.” “Looking at their lists and journal spreads,” he observes, “one senses less intentionality than a straightforward interest in prettification.” He doesn’t seem to approve of the way bullet journaling “fits neatly into the perennially irritating self-help genre,” and “yes,” he says, “if you follow bullet journalists online, you see many doodled sunflowers next to their things-to-do lists.” But, he concedes, “there is something substantial” there nonetheless. Given that he goes on to once more affirm that Carroll’s systematic use of notebooks belongs in the story he’s telling and even, as he notes, has a unique place, as Carroll is rare in himself thinking of the notebook “as a tool, wonder[ing] how it actually works,” I didn’t see why he got so grudging about it there for a while. Michael of Rhodes was interested in “prettification” too, as was the fishbook guy, after all!

Like the Florentine accountants, Renaissance artists and early modern scientists before him,” Allen says, “he’d come to understand his notebook as a crucial tool for the mind, a way to turn intangible thoughts into more concrete written ideas that could more easily be manipulated.” So far so good, but once Carroll’s system becomes popular and highly commercial, and “bullet journaling was everywhere,” Allen starts to get a bit sniffy about it—especially about the “huge online community of bullet journalists who took to social media to celebrate and share their own journals.” “Looking at their lists and journal spreads,” he observes, “one senses less intentionality than a straightforward interest in prettification.” He doesn’t seem to approve of the way bullet journaling “fits neatly into the perennially irritating self-help genre,” and “yes,” he says, “if you follow bullet journalists online, you see many doodled sunflowers next to their things-to-do lists.” But, he concedes, “there is something substantial” there nonetheless. Given that he goes on to once more affirm that Carroll’s systematic use of notebooks belongs in the story he’s telling and even, as he notes, has a unique place, as Carroll is rare in himself thinking of the notebook “as a tool, wonder[ing] how it actually works,” I didn’t see why he got so grudging about it there for a while. Michael of Rhodes was interested in “prettification” too, as was the fishbook guy, after all!

Allen’s overall conclusion is both convincing and eloquent. “I see the story of Europe’s adventure with the notebook,” he says, “as one of enlargements—intellectual, economic, creative, emotional—as curious minds expanded to interact with, and fill, the blank pages that notebooks represented.” The “material simplicity” of the form is its value:

It challenges us to create, to explore, to record, to analyse, to think. It lets us draw, compose, organize and remember —even to care for the sick. With it, we can come to know ourselves better, appreciate the good, put the bad in perspective, and live fuller lives.

—even to care for the sick. With it, we can come to know ourselves better, appreciate the good, put the bad in perspective, and live fuller lives.

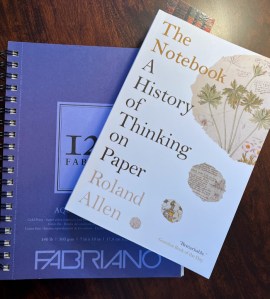

I expect most of us have used notebooks in various ways over our lives, for taking notes in class, as diaries, as repositories of ideas or quotations or recipes or sketches. Reading Allen’s book invites reflection on our own engagement with the history he tells. Reading his chapter on the first Florentine notebooks, I realized that the watercolor sketchpad I had recently bought was made by Fabriano, which he discusses as “the world’s oldest continually operating paper-making company”—it was established (as my sketchbook advertises on its cover) in 1264. I loved that moment of connection. Allen’s main point is that this everyday item, which we now take for granted in its multiplicity of forms and uses, really was revolutionary, changing not just the way we make notes but the way we think. If by any chance you were looking for an excuse to buy a new one—one of these beautiful ‘made in Canada’ ones, say—there it is!