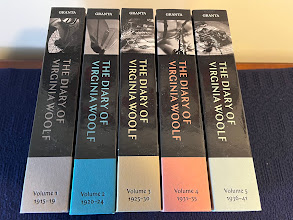

I recently treated myself to the complete Granta editions of Woolf’s diaries. I wanted to mark the finalization of my divorce last month, and this felt right, somehow—more a reflection of the life I am trying to build now, in this room of my own, than, say, jewelry would be. I thought, too, that reading through them would make a good summer project for me, especially if I made writing about reading them a bit of a project as well. I say “a bit of” because I don’t have big ambitions for it. I don’t necessarily want to tie myself to a schedule or make promises, if only to myself, that I then don’t keep but feel bad about! But I do think it will be motivating to have the intention to post updates of some sort. We’ll see what unfolds.

I recently treated myself to the complete Granta editions of Woolf’s diaries. I wanted to mark the finalization of my divorce last month, and this felt right, somehow—more a reflection of the life I am trying to build now, in this room of my own, than, say, jewelry would be. I thought, too, that reading through them would make a good summer project for me, especially if I made writing about reading them a bit of a project as well. I say “a bit of” because I don’t have big ambitions for it. I don’t necessarily want to tie myself to a schedule or make promises, if only to myself, that I then don’t keep but feel bad about! But I do think it will be motivating to have the intention to post updates of some sort. We’ll see what unfolds.

This morning I started on Volume 1, which covers 1915-19. I read the foreword by Virginia Nicholson; the editor’s preface, by Anne Olivier Bell; the introduction by Quentin Bell; and then, finally, the first section of diary entries, from January 1915. They end abruptly because, as the editor’s note explains, Woolf “plunged into madness” in February; the diary does not pick up again until 1917. It seems inevitable that one key effect across the whole of the diaries will be this kind of dramatic irony: after all, it is impossible not to know, now, how her life ended. At the same time, and I think this is not as obvious as it maybe sounds, it seems important that she did not know this. When someone ends their own life it is hard not to see that as the most significant and meaningful thing, not just about them as people, but about the life they lived up to that decision. I’ve always been very moved by the conclusion of Winifred Holtby’s memoir of Woolf, which was published in 1932—Holtby did not know, and would never know (as she died in 1936), about Woolf’s suicide. “For all her lightness of touch, her moth-wing humour, her capricious irrelevance,” Holtby says,

she writes as one who has looked upon the worst that life can do to man and woman, upon every sensation of loss, bewilderment and humiliation; and yet the corroding acid of disgust has not defiled her. She is in love with life. It is this quality which lifts her beyond the despairs and fashions of her age, which gives to her vision of reality a radiance, a wonder, unshared by any other living writer. . . . It is this which places her work, meagre though its amount may hitherto have been, slight in texture and limited in scope, beside the work of the great masters.

“She is in love with life”: it would be too simple to say that this is exactly what the diary communicates so far, but it is certainly very full of living. A central preoccupation at this point is the search for new London lodgings that ends with the Woolfs leasing Hogarth House, where they also then launched the Hogarth Press. During this period The Voyage Out is moving towards publication, but she mentions it explicitly only once that I noticed; the editor suggests that nonetheless it was very much on her mind and that the stress of its impending release contributed to the collapse of her mental health.

Something that is immediately notable to me is how populated Woolf’s world is. I am torn so far between checking each footnote explaining who somebody is and just taking the cast of characters for granted, as she obviously does. It is interesting to know, but distracting to keep finding out, because Woolf mentions so many different people. My mother, whose interest in Woolf long predates my own,* explained once that part of what drew her to the diaries, in addition of course to Woolf’s voice—about which more in a minute—was being plunged into that community. I already see her point: everybody just seems so interesting, so busy with art and politics and love affairs. There is so much bustle, and while much of it (like the house-hunting) is quotidian and familiar, there is also something extraordinary about the way Woolf and her circle of friends wanted to be in the world, as intellectuals and creators and radicals—which is not to idealize them, or her, or to deny the privilege and snobbery that occasionally show through.

There are two related but separate things, I suppose, that make these diaries worth reading. One is Woolf—who she was as she wrote them and who she became. The other is the diaries themselves—what they are like to read, what they offer us as (if you’ll forgive the word) texts. Lots of people have kept diaries that are primarily of documentary interest; Woolf’s diaries, on their merits, are also of literary interest, or so I think it is generally agreed. It seems odd to say “they are great examples of the form” when that form is something so personal. The goal of keeping a diary is not generally to publish it, after all, and there can hardly be a model for how to write about and for oneself. But Woolf is a good writer no matter the form or purpose of her writing, or perhaps it is more accurate to say that the kind of good writer Woolf is suits the darting, episodic, idiosyncratic form of a diary. Already the entries are shot through with evidence of her brilliance, from vivid bits of description (“the afternoons now have an elongated pallid look, as if it were neither winter nor spring”) to moments of acid social commentary:

There are two related but separate things, I suppose, that make these diaries worth reading. One is Woolf—who she was as she wrote them and who she became. The other is the diaries themselves—what they are like to read, what they offer us as (if you’ll forgive the word) texts. Lots of people have kept diaries that are primarily of documentary interest; Woolf’s diaries, on their merits, are also of literary interest, or so I think it is generally agreed. It seems odd to say “they are great examples of the form” when that form is something so personal. The goal of keeping a diary is not generally to publish it, after all, and there can hardly be a model for how to write about and for oneself. But Woolf is a good writer no matter the form or purpose of her writing, or perhaps it is more accurate to say that the kind of good writer Woolf is suits the darting, episodic, idiosyncratic form of a diary. Already the entries are shot through with evidence of her brilliance, from vivid bits of description (“the afternoons now have an elongated pallid look, as if it were neither winter nor spring”) to moments of acid social commentary:

We went to a concert at the Queen’s Hall, in the afternoon. Considering that my ears have been pure of music for some weeks, I think patriotism is a base emotion. By this I mean … that they played a national Anthem & a Hymn, & all I could feel was the utter absence of emotion in myself & everyone else. If the British spoke openly about W.C.’s, & copulation, then they might be stirred by universal emotions. As it is, an appeal to feel together is hopelessly muddled by intervening greatcoats & fur coats. I begin to loathe my kind, principally from looking at their faces in the tube. Really, raw red beef & silver herrings give me more pleasure to look upon.

My favorite bit in this first instalment was this thoughtful observation:

Shall I say “nothing happened today” as we used to do in our diaries, when they were beginning to die? It wouldn’t be true. The day is rather like a leafless tree: there are all sorts of colours in it, if you look closely. But the outline is bare enough.

Looking closely, seeing all the colours in an ordinary day: that sounds like an artist’s job to me, a painter’s but also a novelist’s, and it is something anyone can practice by writing in their diary, though the results are unlikely to be as scintillating as hers.

*Just as my father’s love of Trollope and the other Victorians predates mine—I am so fortunate, as I often now reflect, both in my parents themselves (much love to you both, if you are reading!) and in their literary influences on me. Their bookshelves were always both inspirational and aspirational to me when I was growing up, and important as it was that they read to us, I think it was even more important that we always saw them reading all kinds of books.

I love this, Rohan.

I wish I had the energy (or will?) to keep a diary. If I did, it would be filled with “…judged Champagne today…gave a Masterclass on Rioja…wrote up tasting notes on global Rose wines…played Real Tennis at Queens, poorly…played Squash Rackets at Cumberland, adequately…looked after grandson Bart and we played ‘Baby Pilates’…and tracked down a million recipes I both cook (for husband) and write up to go with wine tasting notes for an international publication. Interspersed would be ‘Yet another meeting on the project down at XXX Hospital; the builders are causing trouble, again’. Read a bit of the current Trollope novels and started compiling the Criticism due in a fortnight for the current one; pretty much as expected for this later novel. Visited early Anselm Kiefer at the Ashmo; some very interesting works, but hardly less depressing than almost everything he produces, but learnt about his link to the poetry of Rainer Maria Rilke, which I had NOT known. Worked on the quilt for ‘Baby Sibling’ (next grandchild), watching whatever was on BBC IPlayer, sort of. Prepared Sunday School materials and activity for the kiddos.”

…etc.

Like your life, mine runs in cycles, but I wish mine were more interesting. It’s the same stuff week-in, week-out.

Really do like your Novel Readings.

Thanks,

Patricia

LikeLike

I guess one of the things that makes the difference between Woolf and the rest of us (and my own days also don’t yield much that seems interesting) is that she can see or find the spark of life in those daily routines as well as in the sudden turns or revelations. Can this kind of insight (and the ability to articulate it) be learned? The advocates of things like morning pages seem to believe it can.

LikeLike

When I did my undergrad at Concordia’s Liberal Arts College, I wrote my final Honours paper on Woolf and time. And that final quotation you included reminds me of that perfect ending to To the Lighthouse and the artist Lily, which is as perfect a novel as anyone has ever written. I think I even read some of the diaries at the time, though more likely the letters, also fascinating, for my paper. All I remember of them was her obsession with clothes, which I share. 😉

I’m trying to remember what I did when my divorce was finalized, but I suspect is was something way more prosaic involving a friend and copious tumblers of Prosecco…

LikeLike

Hmm, Prosecco – a good idea. I didn’t feel like celebrating, as it is such an emotionally complex thing (as I’m sure you know), but it is nonetheless an occasion that seems worth observing in some way.

I’ve always found Woolf’s fiction more elusive than her nonfiction, and I recently reread Mrs. Dalloway and still could not find it transcendent in the way I know many people do. But To the Lighthouse – yes, that ending is perfection.

LikeLike

Of course, you had a long marriage and children. I have a year of yuck…so much easier for me. It is worth marking because it is such a life-change and transition. But the solitary life too has its rewards, as you are learning.

Hmmm, I would agree with you about Mrs. Dalloway. I think To the Lighthouse the most accessibly “transcendent” and my favourite. I have a soft spot for The Voyage Out (as conventional a novel as Woolf wrote, I guess) and Orlando, kind of fun. Because my problem with Woolf has always been her humourlessness. Same with Lawrence.

LikeLike

I kept diaries assiduously when I was a teenager, long, passionate outpourings of ambition, frustration, drama… and left them all behind when I ran away from home. Goodness knows what my parents made of them. There’s not much that I regret in my life but I do wish I could read them now, I was a good writer even then and I was paying attention to world affairs, so I think they would be interesting to read.

By the time my divorce came round, I had met someone new (who eventually became The Spouse though I hesitated long and hard before risking to trust again). As well as having a real job, he was the leader and arranger of a very popular 11-piece swing jazz band as a hobby. They had a gig that night, one that I needed to ‘frock up’ for among Melbourne’s glitterati, and so we danced the night away and then stayed the night in the city in Melbourne’s grandest hotel. It was fearsomely extravagant, but I think there is something important about celebrating a new beginning with something you’ve always wanted.

LikeLike

I still have my teenage diaries and I mostly find them embarrassing. I will probably do away with them at some point if only to prevent anyone else from laughing at my angst and pompousness the way I do when I reread them – although to be fair to my younger self, being a teenager does pretty much suck especially when you are bookish. I can understand why you regret losing yours.

New beginnings are definitely worth celebrating. Dancing the night away! How glamorous. 🙂

LikeLiked by 1 person

I thoroughly enjoyed reading this, Rohan, and could say so much but will keep to three points. Sessional teaching requires being able to adapt and establish new focus areas but one of the great joys of my late career has been the opportunity to return to Modernism. I love in Woolfâs writing that capacity for a sort of precise perceptive observation in the moment. And I am flashing back pleasantly to the major Woolf exhibition at the National Portrait Gallery, which coincided with a holiday in London during a broiling heat wave in 2014.

>

LikeLike

“Precise perceptive observation in the moment”: so nicely put (form imitating content!). I think it is not trendy these days to attribute good writing to talent or even genius (that works against the ‘it’s all a craft, you can learn and teach it’ narrative that abounds in this MFA world) but it is hard not to think that Woolf’s ability to do that so casually in something like a diary is a sign that there’s something extraordinary about her mind.

LikeLike

A beautiful post.

I kept a diary as a teenager but as an adult, I have always found the idea of putting my thoughts to paper much too revealing so I have never really managed to go beyond a few innocuous jottings before abandonning the attempt.

Your final comment really resonates with me. A reader begets a reader 🙂

My father was a voracious reader. My children all read a lot but there is one in particular who is as consumed by reading as I am and as my father was.

LikeLike

There have been some moanings on social media recently about a story saying parents have almost stopped reading to their children, which does seem both sad and bad – but seeing our parents reading is surely at least as influential. I tutored a little fellow once who was struggling with reading in school and the first thing I noticed when I showed up at his very well-appointed home was the total absence of books.

LikeLike

What a lovely gift to yourself. I’m so far behind in my TLS reading that I only got to Emily Kopley’s review of the Granta edition two days ago. She mentions Woolf’s comment on the beauty of the world as too much for one pair of eyes. Enough to float a whole population in happiness if only they would look.

What a feat, to maintain such a position despite everything. You have an enviable feast before you.

LikeLike

Despite everything – indeed. I wonder if that capacity to see so much contributes to the inability to find balance, like George Eliot’s point about the roar on the other side of silence. The price of being so attuned might be getting overwhelmed.

LikeLike

Always a narrow ledge over a precipice.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I do wonder if anyone in my family will ever open one of the thousands of books in the bookshelves behind me – all I can do is keep accumulating and leave the door open 😉

LikeLike